The Edinburgh Medical School

The Edinburgh Medical School was founded in 1726 by an act of the Town Council. It stood unrivalled as the most vibrant medical faculty in Britain and Ireland until the early nineteenth century and its reputation for excellence was challenged only by Leiden. The Scottish capital attracted large numbers of international students and offered a medical education often unavailable to students in their own countries. Throughout the eighteenth century, Edinburgh was a hub of intellectual and scientific activity and its medical school was the jewel in the university’s crown. Its foundation was, in part, a deliberate policy to bolster the economy and improve the city by attracting foreign students and retaining Scottish ones, who at that time typically completed their medical education on the continent at great expense. By the 1750s the university was home to around 300 medical students – half of the entire student body.

University of Edinburgh Medical School (Gary Campbell-Hall, 2022)

The university offered a full complement of lectures and one of the first courses in Europe in clinical medicine. At Edinburgh’s new medical school, future physicians, surgeons and apothecaries, as well as those who would go on to specialise in other fields, such as botany, natural history or chemistry, rubbed shoulders on the faculty benches and gathered together in the course of their training at the hospital, the famous Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. The medical school’s reputation flourished as a succession of brilliant professors were appointed, such as William Cullen (1710-90), James Gregory (1753- 1821), and Joseph Black (1728-99), the discoverer of carbon dioxide.

188 students from America and the West Indies are recorded as graduating from Edinburgh during the eighteenth century. The Medical School was a particular draw for students from the enslaving American colonies of Virginia, Maryland, Carolina and Pennsylvania and the Caribbean islands of Jamaica, Antigua, Barbados and St. Kitts, who arrived with letters of introduction in hand and money in their pockets. In terms of the West Indies, Edinburgh drew the greatest number of graduates from the island of Jamaica (almost 30%). However, the number of students who studied medicine without graduating, as was then common, was considerably higher. Large numbers of Scottish, English, and Irish students who studied at Edinburgh also travelled to gain employment in the West Indies. Scottish medical graduates and students of the University of Edinburgh were especially valued due to the large Scottish diaspora there and the known quality of Edinburgh’s medical education. Those lacking the necessary finances to practice in Scotland or England could also work as Guinea surgeons on the Middle Passage. Guinea surgeons, such as Scotland’s Archibald Dalzel (1740-1811), treated enslaved people on British vessels employed in the Atlantic slave trade.

The wealth from slavery enriched the university, infirmary, and city with money being spent on rent, books, instruments, clothes, and of course socialising. By the 1790s the historian Nicholas Phillipson estimates that to live in a ‘genteel manner’ it cost the average student £10 a quarter or £20 for the winter session for bed and board alone. Money was also sent back to the university by grateful alumni who had made successful lives for themselves in the Caribbean as a result of enslavement.

Archibald Ker’s Bequest

The Edinburgh Infirmary for Sick Poor or ‘Little House’ opened in 1729 on Robertson’s Close and received its Royal Charter in 1736. The infirmary was the teaching hospital for the University of Edinburgh Medical School and was instrumental in establishing Edinburgh’s reputation as a centre of medical excellence and Enlightenment. However, the medical school and infirmary also produced generations of medical practitioners who supported and propagated slavery and imperialism in the British empire, while growing wealthy from the fees of students who came from the colonies. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the hospital benefited substantially from the charitable donations, subscriptions, and legacies of individuals who derived their wealth from enslavement, the trade in enslaved people, and the goods they produced.

Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh (c.1751)

It was at a meeting on 9 July 1750 that the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh first became aware of the substantial and unique bequest which had been left to it on the island of Jamaica. At the meeting George Drummond informed the managers that he had received a letter stating that Archibald Ker, a Scottish surgeon from St Thomas-in-the-East, near Kingston, had died leaving his Redhill pen to the infirmary.

In his will, Ker bequeathed ‘the annual profits of his estate (real and personal) towards and for the use of the Royal Infirmary at Edinburgh’. Ker went on to further specify that it was his ‘resolute intention and desire that the said estate be kept and not sold or otherwise disposed of’. Legally this meant that the infirmary had been gifted an estate it could never sell, together with an enslaved workforce that it could presumably neither sell nor emancipate.

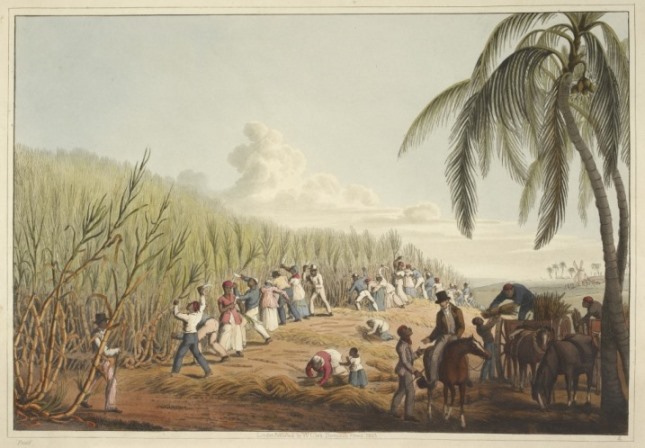

Redhill consisted of 420 acres in the sugar parish of St Thomas-in-the-East, around 27 miles from Kingston. The property was a pen, as opposed to a plantation. While the best land was used for the more profitable business of growing sugar cane, coffee, and tobacco, pens were devoted to rearing livestock for the larger estates.

Ker’s estate held 39 enslaved people (21 males, 18 females) valued at £2,115 Jamaican currency. Of the 39 enslaved, two were listed as children.

Donations from the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

However, Archibald Ker’s legacy was not an indiscriminate act of philanthropy from Jamaica but rather part of a much larger appeal for funding on behalf of the hospital.

In July 1745 the managers received bills of exchange from Mr Alexander McFarlane for the sum of £500. MacFarlane (1702-55) was very wealthy and owned 5,605 acres on the island and was listed as the owner of 791 enslaved people at probate. A further substantial donation was made by James Barclay who left the infirmary a £200 legacy in 1762. Barclay came from a landed Scottish family in Cairness and had worked his way up from bookkeeper (who supervised enslaved labourers in the sugar cane fields) to the post of auditor general of the revenues. At the time of his death, he owned a large estate of some 3,149 acres in Westmoreland. Smaller donations were received by the likes of Dr John Cochrane of Kingston, Jamaica. Donations which could be traced to slave-related wealth were also received from other Caribbean islands including Antigua, Tobago, Montserrat, Barbados, and St Kitts.

William Clark, 'Slaves cutting the sugar cane', Ten Views in the Island of Antigua (1823)

The infirmary’s financial ties to slavery did not end with the eighteenth century. By the mid-nineteenth century, it was evident that the hospital had become unfit for purpose and it was decided that the construction of a new hospital would begin on Lauriston Place.

As was the case from the infirmary’s foundation funding was a fundamental and continued concern for the managers. Public subscriptions were sought and the published subscription list of 1868 shows that £51,168 was raised. Among the subscribers were individuals who had significantly profited either directly or indirectly from the practice of slavery.

The largest donation came from one Mrs Buchanan who donated a staggering £5,000. Jane Buchanan (d.1883) was the widow of James Buchanan (1785-1857), a Scottish West India Merchant who profited from commerce related to chattel slavery and made his fortune in Grenada, Jamaica, and Brazil before returning to Scotland to live handsomely off the profits.

Other benefactors included William Frederick Burnley (1810-1903), the son of William Hardin Burnley (1780-1850), the largest owner of enslaved people in Trinidad, the well-known Dundee linen manufacturer David Baxter (1793-1872), and The Carron Company who made gigantic iron sugar pans which were used to boil sugar cane syrup and exported to the Caribbean and America. In a subsequent subscription list of 1879, among the names of those who profited from slavery were Julia Caroline Hoyes (1818-91) and her husband John Hoyes (1806-1885) who owned the Prospect estate in St John, Francis Brown Douglas (1814-85) who was awarded compensation as owner of Bellaire in St Vincent, and the Edinburgh Tobacco Boys School.

The Edinburgh Royal Infirmary was complicit in and benefitted substantially from the ownership of enslaved people and charitable donations derived from the profits of slavery, from the time of its foundation until at least the end of the nineteenth century. The enslaved on Ker’s pen and the enslaved ‘owned’ by those who made charitable donations to the infirmary were far from beneficiaries of the British colonial project. All of these enslaved people were exploited and the profits of their labour harnessed to further the improving and Enlightened goals of the hospital.

During their early years the Edinburgh Medical School and the Royal Infirmary were servants of empire, educating the next generation of medical professionals, helping to strengthen, enlarge, and cultivate Britain’s colonial world in the West Indies, America, and elsewhere, and in doing so enabling the expansion of slavery and the trade in enslaved people.

Author Bio

Dr Rachael Scally is a historian of British and Irish medicine and empire. She is a research affiliate in the faculty of history at the University of Oxford and her current project, which is sponsored by a British Academy and Leverhulme research grant, examines Edinburgh-trained medical practitioners and slavery in the British Caribbean, c.1726-1834.

Follow our Twitter account @RCPEHeritage or our Facebook page or sign up to our newsletter to get notifications of new blog posts, events, videos and exhibitions.