Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

Mourning is the outward display of grief. It can make the personal, societal. It is loss shared. For much of history the formal rituals surrounding mourning were widely understood. You knew what was expected of you, depending on your class, gender and relationship with the deceased.

In the 1500s and 1600s grief was believed to manifest as physical diseases and could be treated by physicians using leeches, laxatives and vomits. According to one physician, Jeremiah Wainwright, writing in 1707, ‘Diarrhoeas from immoderate Grief, are incurable’.

Mourning rituals reached their peak with the Victorians – the bereaved fainted, cried, or wasted away. This began to change by the late 1800s with the rise of secularism and the anonymity of large cities, but the biggest change came with the Great War. Ostentatious mourning was seen as insensitive and instead people began to mourn more privately. Grief was removed from public view and mourners were expected to hide their sorrow.

This is a stereoview card, one of the earliest forms of 3D photography.

The posed images were taken by an American photographer, Benjamin Kilburn, who was known for his landscapes and studies of American life.

The photograph shows a recreation of a wake and contain many of the elements traditionally associated with Irish and Scottish wakes.

One visitor to a wake in country Tyrone in the early 1800s described ‘laughing, and story-telling, and singing, and drinking, and crying – all going on helter-skelter together’.

The history of the wake stretches back to pre-Christian times, when family members and friends would guard the body to protect it from both supernatural and natural predators.

Other rituals were designed to keep out malicious spirits, including stopping clocks at the time of death and covering mirrors.

This skull, also known as a calavera, was hand-painted in Guerrero, Mexico. Calaveras are used in the Mexican celebrations of the Day of the Dead.

These celebrations combine the culture of indigenous people with Islamic and Christian traditions brought to Mexico by the incoming Spanish.

During this celebration shop windows and home altars are decorated with imagery which combines Christian symbols, such as images of saints and crucifixes, with skulls and dancing skeletons.

While the concept of death is mocked through this imagery, the death of individuals is treated respectfully – this symbolism is not used in funerals and individuals are celebrated through stories, song and poetry.

This holiday has become increasingly commercialised in recent decades and in the larger cities much of the celebration is geared towards overseas tourists rather than residents.

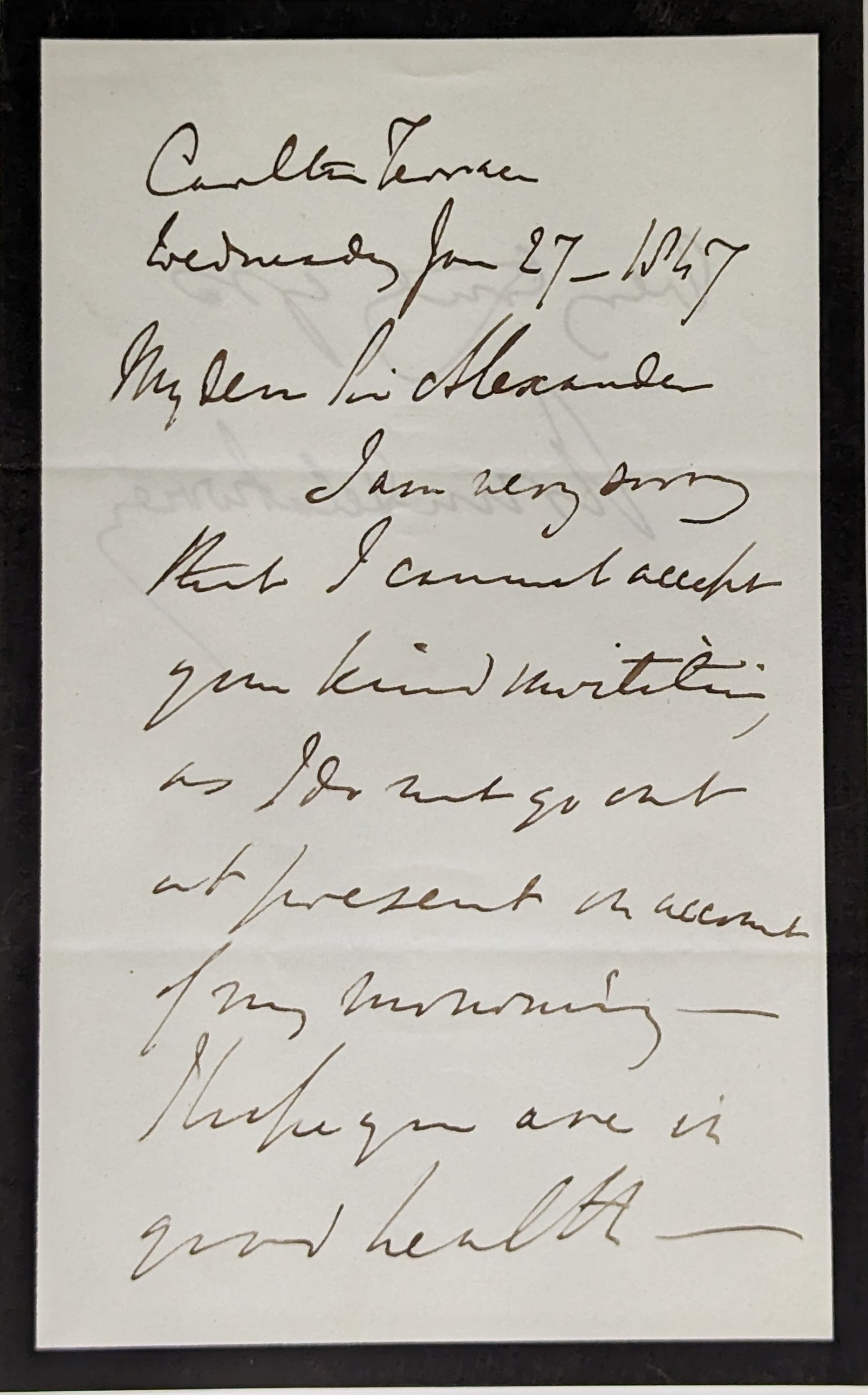

In this reply to a dinner invitation, Howard writes to say that ‘I cannot accept your kind invitation, as I do not go out at present on account of my mourning’.

The letter is dated only a few months after the death of one of Howard’s children, Bernard, and is written on black-bordered mourning stationery.

In some cases, the width of the stationery’s black edge showed the stage of mourning – with thicker black borders signifying the earliest stages of mourning, reducing down to a slim border towards the end of the period of mourning.

The thickness of the border could also demonstrate the extent of the individual’s sorrow and their closeness with the deceased.

Many widows would continue to use mourning stationery for the rest of their lives.

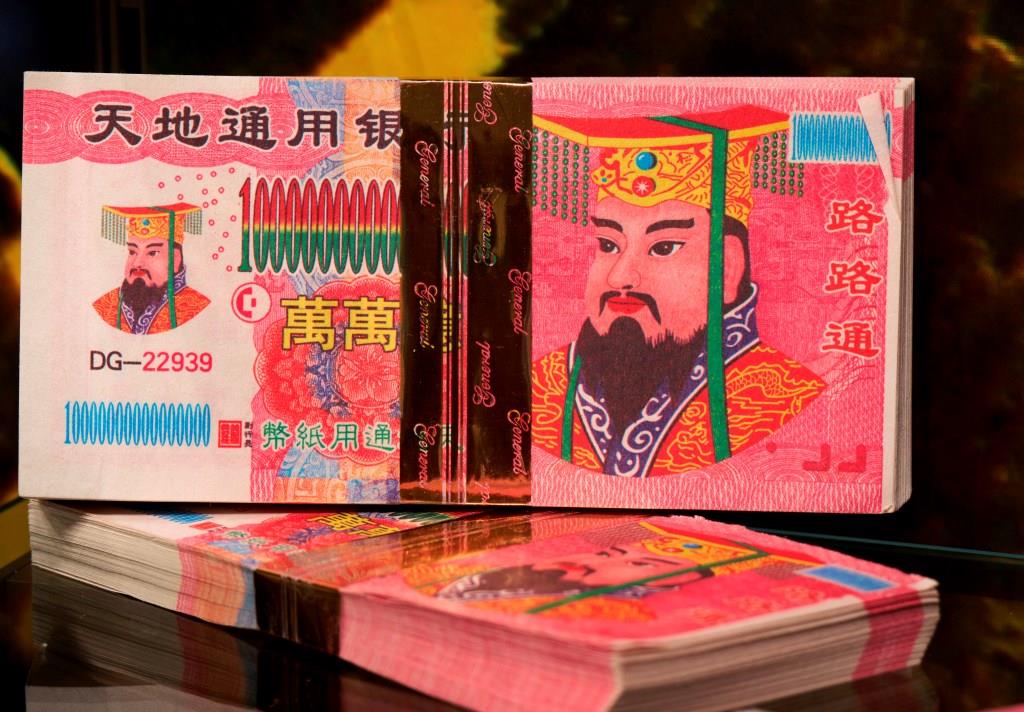

This banknote is not legal tender and is made of joss paper. The figure on the right is the Jade Emperor who, in Chinese folklore, has responsibility for the afterlife. Notes like this are burned by families at their ancestors’ gravesides in order to assist the monetary problems of the deceased in the afterlife.

The burning of joss paper as part of ancestor worship dates back hundreds of years, but the practice of burning hell banknotes is more recent, originating in the late 1800s. It is believed that the word hell was introduced into China by Christian missionaries in the 1700s and 1800s and although it is used for these notes, its meaning here does not have the same negative connotations as in Christian belief, being more akin to the underworld or afterlife.

This blog was developed to accompany the exhibition After Life: A History of Death which ran from 27 October 2023 to 5 July 2024.

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources