The loss of a wife rarely altered a man’s status, but the loss of a husband changed a woman’s life forever. Becoming a widow brought risks, but there was opportunity there as well. Unlike a married woman, in the 1600s and 1700s a widow could inherit land, sign contracts and join professional bodies like trade guilds. Women often took over the trade of their deceased husbands and wielded significant economic power.

Mourning Cape (c.1890s)

This cape was made in the late Victorian period. At that time the culture of mourning clothing was largely focused on women, particularly widows. For these women mourning clothing demonstrated their dependability, faithfulness and their dependence on their deceased spouse.

Mourning clothing could act as a class leveller – the mass-production of relatively cheap black clothes gave the less well-off access to items which, because of strict rules about the style and colour of mourning clothing, appeared superficially to be very similar to that of the wealthy.

Where this wasn’t an option women could also re-purpose and dye clothing or borrow mourning dresses from friends and relatives. Black could be defined quite loosely, when needs must, and dark brown and blue mourning clothing was common.

Mourning Bracelet (c.1850s)

The panel on this bracelet contains hair from the great-grandmother of its owner. The strap is also made from woven human hair.

Relics of human remains have a long history, in Europe associated with the worship of Catholic saints. With the widespread move to Protestantism from the 1500s, the saint’s relic made way for the remembrance of the individual.

Mourning jewellery was so popular in the late 1800s that it spawned a whole industry. Advertisements for hairworkers appeared in national and local newspapers. Their very popularity created concerns – rather than having jewellery made locally, increasingly the hair was sent off to a hairworker for production. This led to the fear that it would be replaced by the hair of another during production.

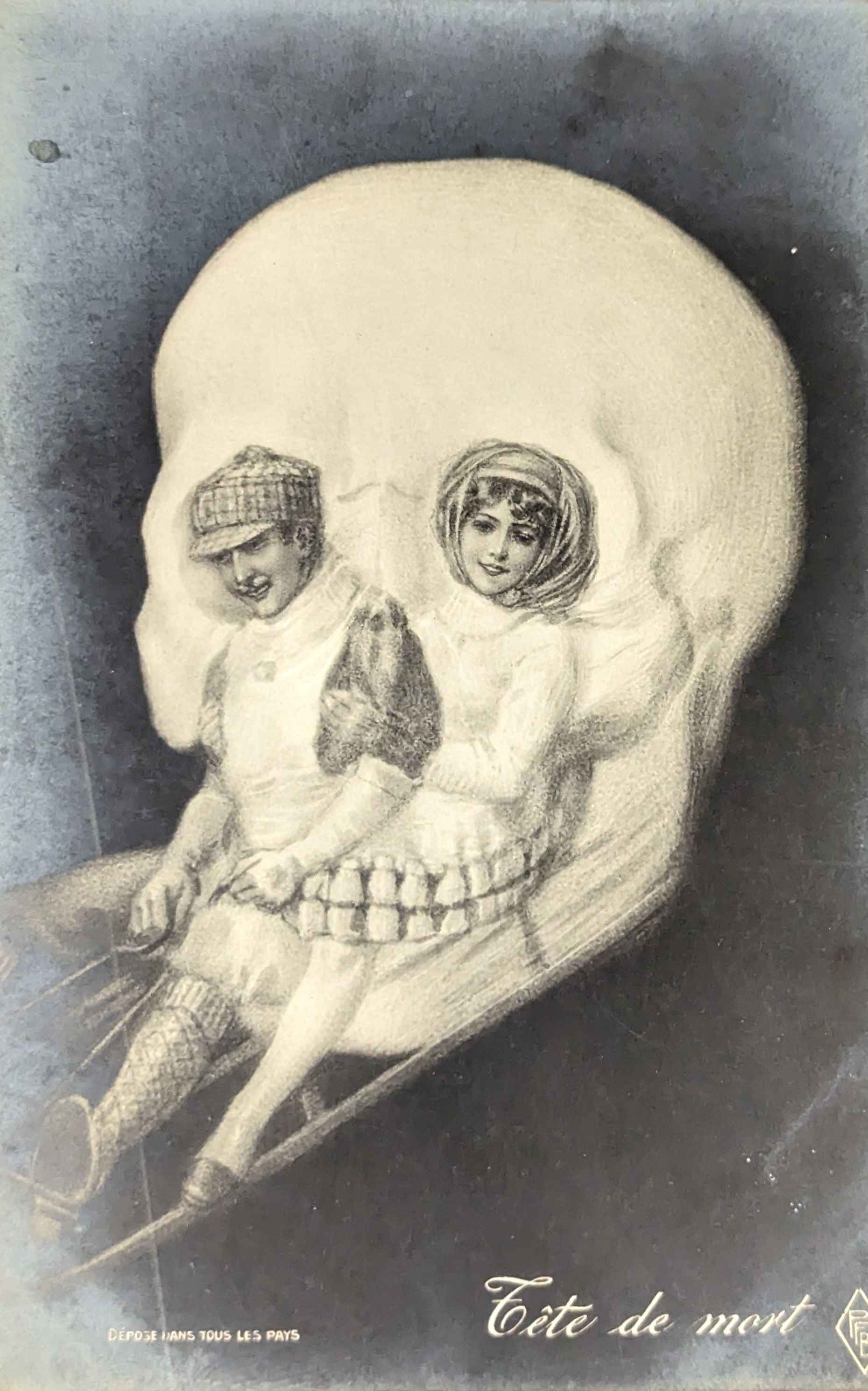

Death’s Head Postcard (c.1890s)

Optical illusions such as this one are known as metamorphic illustrations. Metamorphic skull images became popular in the late 1800s and can be found on greeting cards, jewellery and picture frames.

Conjurors, illusionists and the occult were all popular forms of entertainment in Victorian Britain. You could watch someone escape from a locked box in a dance hall, see ghosts in your own front room with the assistance of a medium or witness the sleight of hand of a street performer.

Printed optical illusions were part of this trend. The production of images meant to be spun, twirled or reflected to produce images included the magic lantern and the stereoscope. Metamorphic illustrations were an extension of this fascination with illusions, combined with the Victorian fascination with death and mourning rituals.

This blog was developed to accompany the exhibition After Life: A History of Death which runs from 27 October 2023 to 5 July 2024.

Follow our Twitter account @RCPEHeritage or our Facebook page or sign up to our newsletter to get notifications of new blog posts, events, videos and exhibitions.