Friends, neighbours, church ministers and philanthropic members of the landed gentry shared medical recipes and ingredients with people in their communities. Travelling salesmen sold mysterious secret remedies door to door. Medical traditions were passed down from mother to daughter through the generations.

For the wealthy, the domestic concoction of medicines could involve long preparation periods and complex distillation methods. For the less well-off medical simples were the most common form of treatment. Simples were items which were usually common to the household or easily acquired locally, and which were taken pure, without mixing them with anything else.

In the 1700s rising consumerism meant that more people were able to buy pre-made medicines from stores. Apothecary shops sold these medicines, but so did booksellers, hairdressers and stationers.

Often the contents of these patent medicines remained the same as their earlier home-made versions. Rhubarb, liquorice and mint were common ingredients. Imported items from overseas were also increasingly included, including sugar, chocolate, spices and plants.

Mary Sayer

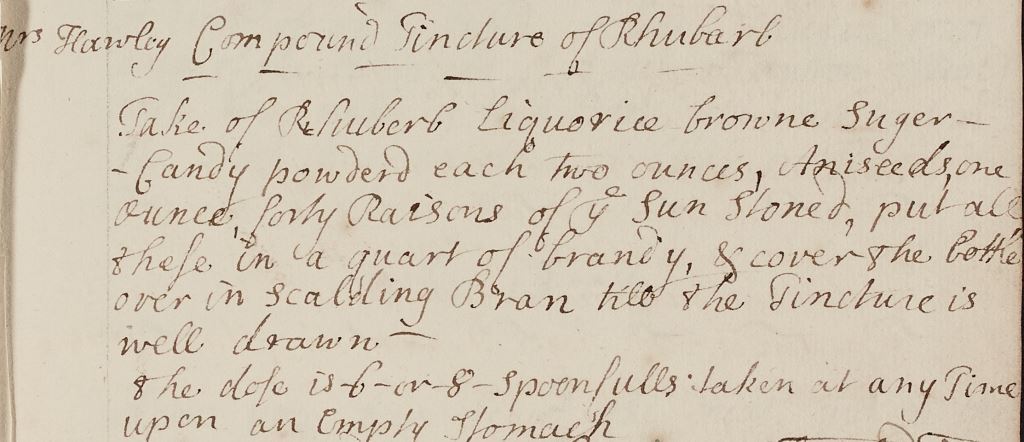

Recipe Book (early 1700s)

These household books contained recipes for food, medicine and domestic tasks. They were written down without any clear distinction made between these categories and food was often used as a form of medicine. Recipe books were usually owned by middling or upper-cass women because they would have had to be completely literate – able to both read and write – as well as have access to bank notebooks on which to write.

This recipe shows the different ‘food’ ingredients that were used as medicine. The ‘Compound Tincture of Rhubarb’ calls for rhubarb, liquorice, brown sugar and raisins. It is not specified, but this recipe was probably used to empty the bowels, because rhubarb was a common laxative.

Dr Gregory’s Stomachic Powder

(1800s)

In the 1700s far more medicines received royal patents than any other invention. Anyone could get a royal

patent for a medicine – its formula had to be unique, but there was no need to prove that it worked. Opportunists cashed in on the popuarity of home remedies and self-diagnosing to create pre-made medicines which could be bought for home use.

This patent medicine, Gregory’s Stomachic Powder, was named after its creator James Gregory. Gregory

was Professor of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh and personal physician to the king. Its characteristic pink colour comes from the rhubarb it contains. Gregory grew the rhubarb used in his medicine at his home in Morningside.

John Kay, A Series of Original Portraits and Caricature Etchings

(1838)

Fishwives, or ‘oyster lasses’, were common figures in the streets of 1700s Edinburgh. The nearest fishing station to the city centre was in Newhaven, two miles away, and the women would walk from Newhaven to Edinburgh’s Old Town carrying the heavy fish creels on their backs. In the 1700s and 1800s oysters were so plentiful that they were considered as cheap snack foods. They were eaten in such quantities that the Bank of Scotland on the Mound now sits on top of a giant heap of discarded oyster shells. The shells themselves, when ground up, were taken to relieve heartburn.

Oysters were so popular that an act of parliament was passed in 1840 which criminalised the stealing of oysters from fisheries. The punishment for the crime was imprisonment for one year.

Madras Curry Powder Tin

[1930s]

Many ingredients in curry powder, including turmeric and cumin, have been used for medicinal purposes for thousands of years. Originally from India, curry was introduced into Britain via the Silk Road trade routes. Curry first began to appear in British cookbooks from the 1740s.

Apothecaries began to sell curry powder and physicians studied its medicinal properties. One Victorian publication, advertising disguised as a medical text, was Curries, their properties, and healthful and medicinal qualities. Its author caimed that curry was a stimulant and was anti-bilious, anti-spasmodic, anti-flatulent, soothing and invigorating. With the usual hyperbole of Victorian advertising the text caimed that the consumption of curry could end poverty in Britain and save the lives of those who had been 'brought to the brink of the grave'.

This blog was developed to accompany the exhibition FOOD: Recipe or Remedy, which runs from 28 April 2022 to 27 January 2023.

Follow our Twitter account @RCPEHeritage or our Facebook page or sign up to our newsletter to get notifications of new blog posts, events, videos and exhibitions.