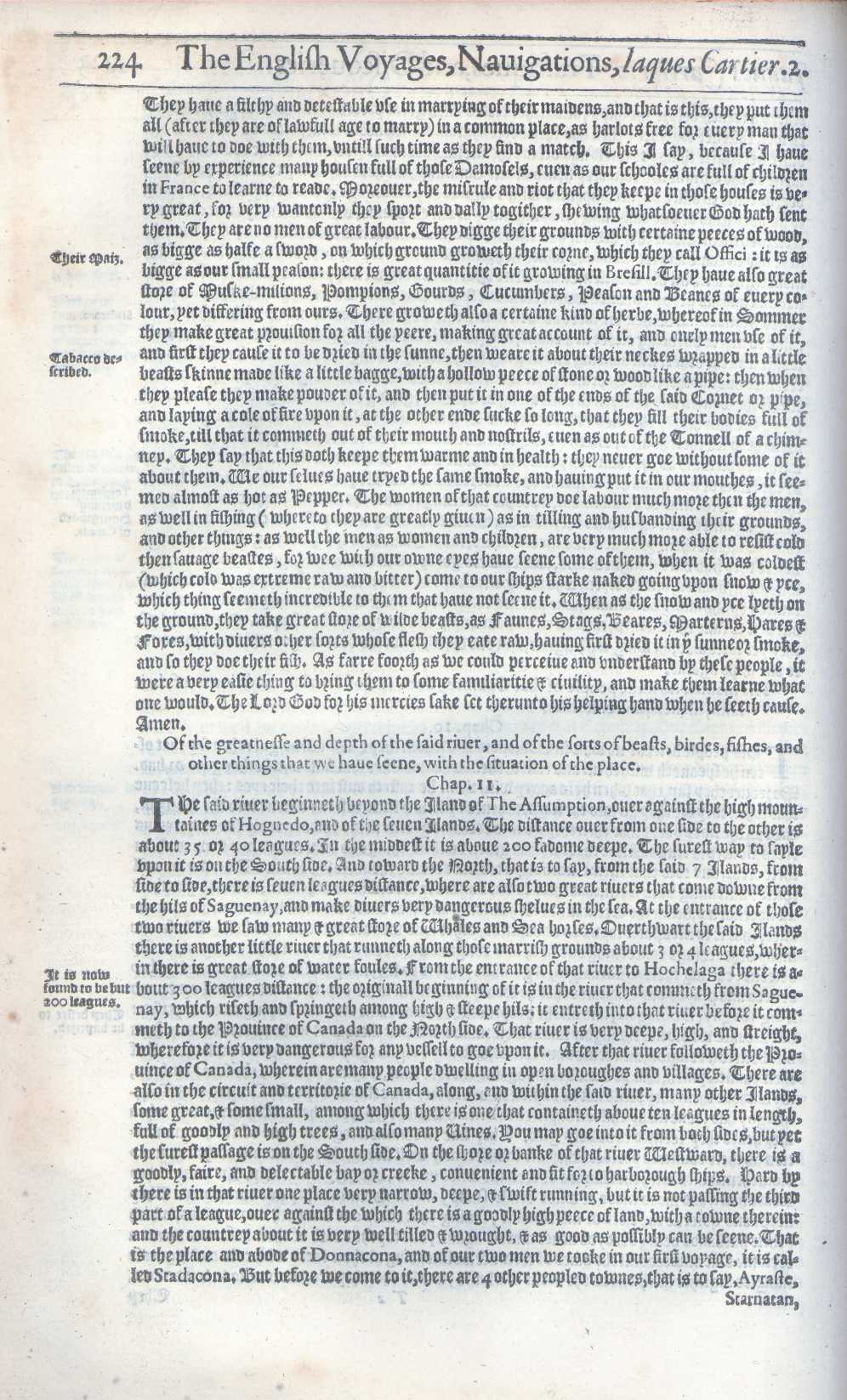

Many plants contain nicotine but those commonly cultivated for tobacco are indigenous to America. The first clear description of tobacco smoking was made by Captain Jacques Cartier during his voyage to North America in 1535.

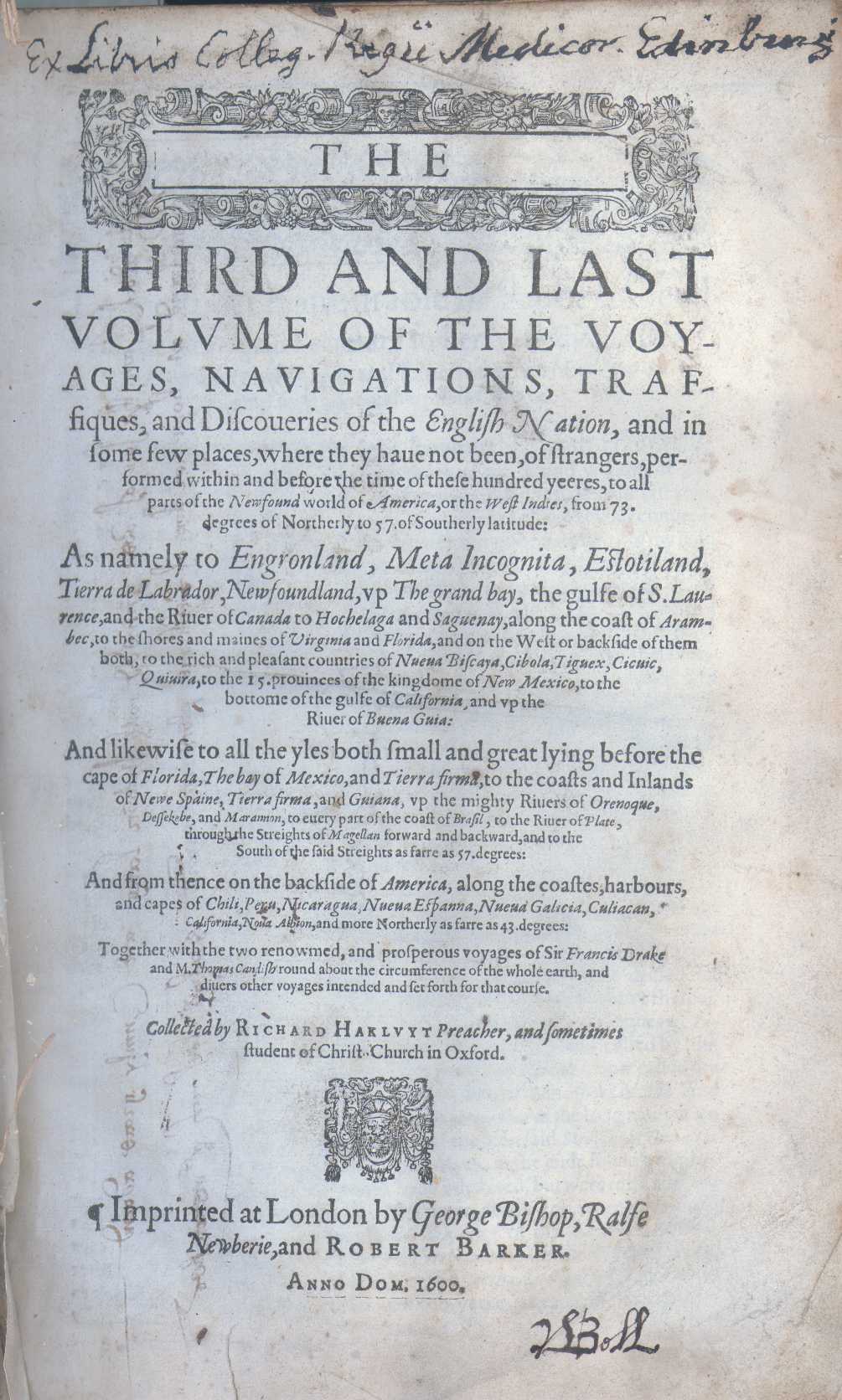

Richard Hakluyt (1552-1616)

The third and last volume of the voyages, navigations,

traffiques and discoveries of the English nation

London, 1600

Hakluyt's collection of voyages includes Cartier's account, where he described how the indigenous people he met when he arrived at the island of Montreal offered him tobacco. This was the first recorded report of native Americans smoking tobacco for its medicinal benefits.

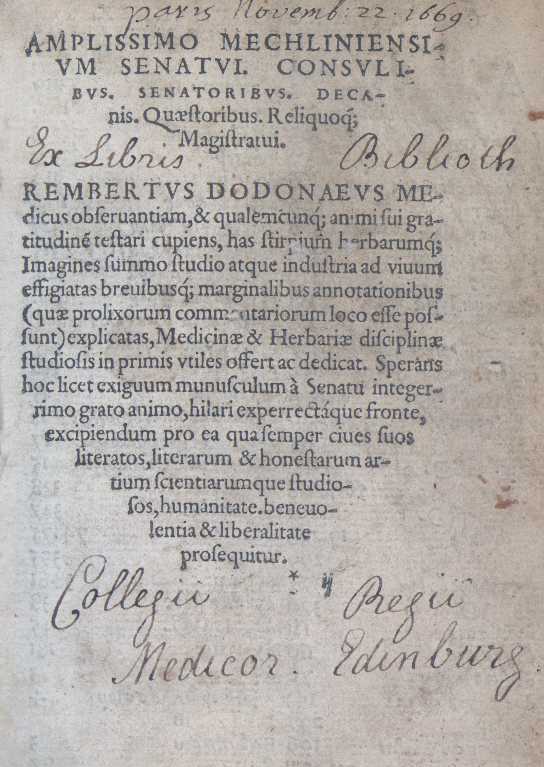

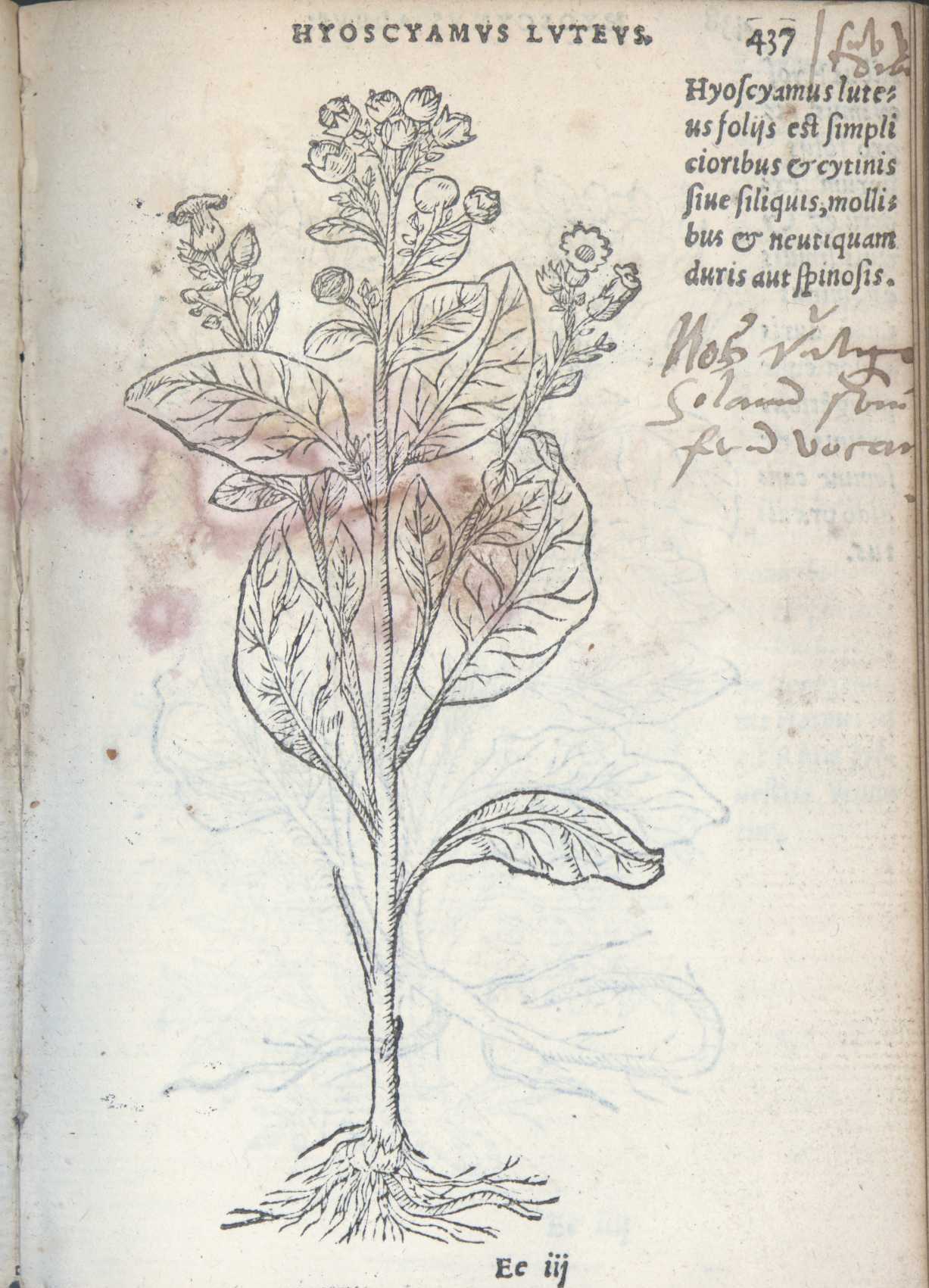

Rembert Dodoens (1517-1585)

De stirpium historia commentariorum imagines

Antwerp, 1553

Dodoens was court physician and professor of medicine at Leyden. His reputation, however, is based on his work in botany. The above herbal contains the first printed illustration of the tobacco plant. Dodoens named it hyoscyamus luteus.

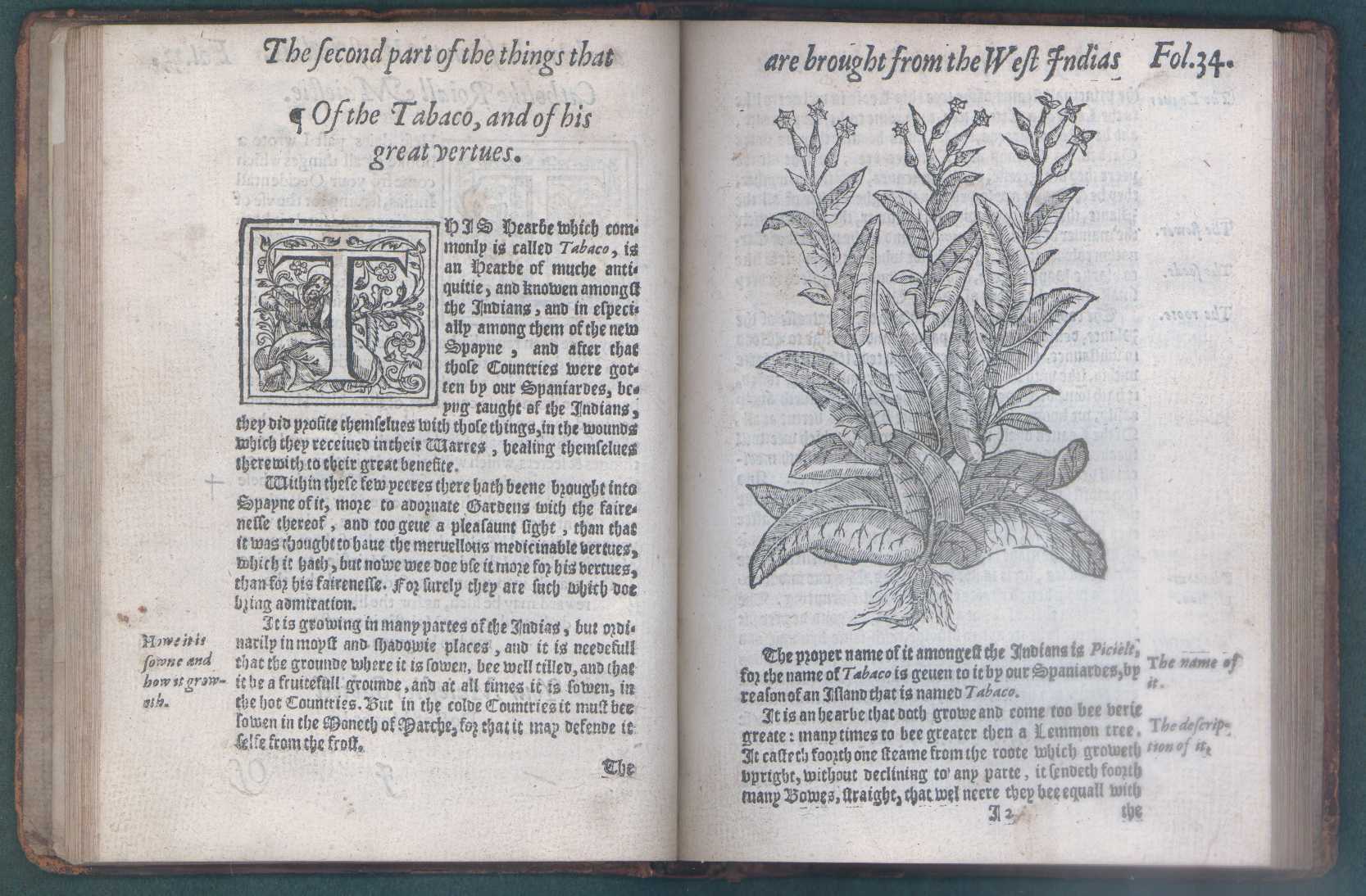

Nicolas Monardes (ca. 1512-1588)

Medicinall historie of things brought from the West Indies

London, 1580

Monardes was the first physician to write about the medicinal use of tobacco. He described over sixty-five diseases which he claimed it could cure. His treatise was so influential that it led to the idea that tobacco could cure all diseases and conditions. It introduced to Europe the words tabacco and nicotaine, and started a controversy which was to be debated for the following two centuries as the medical world was split over the benefits or harmful effects of the tobacco plant.

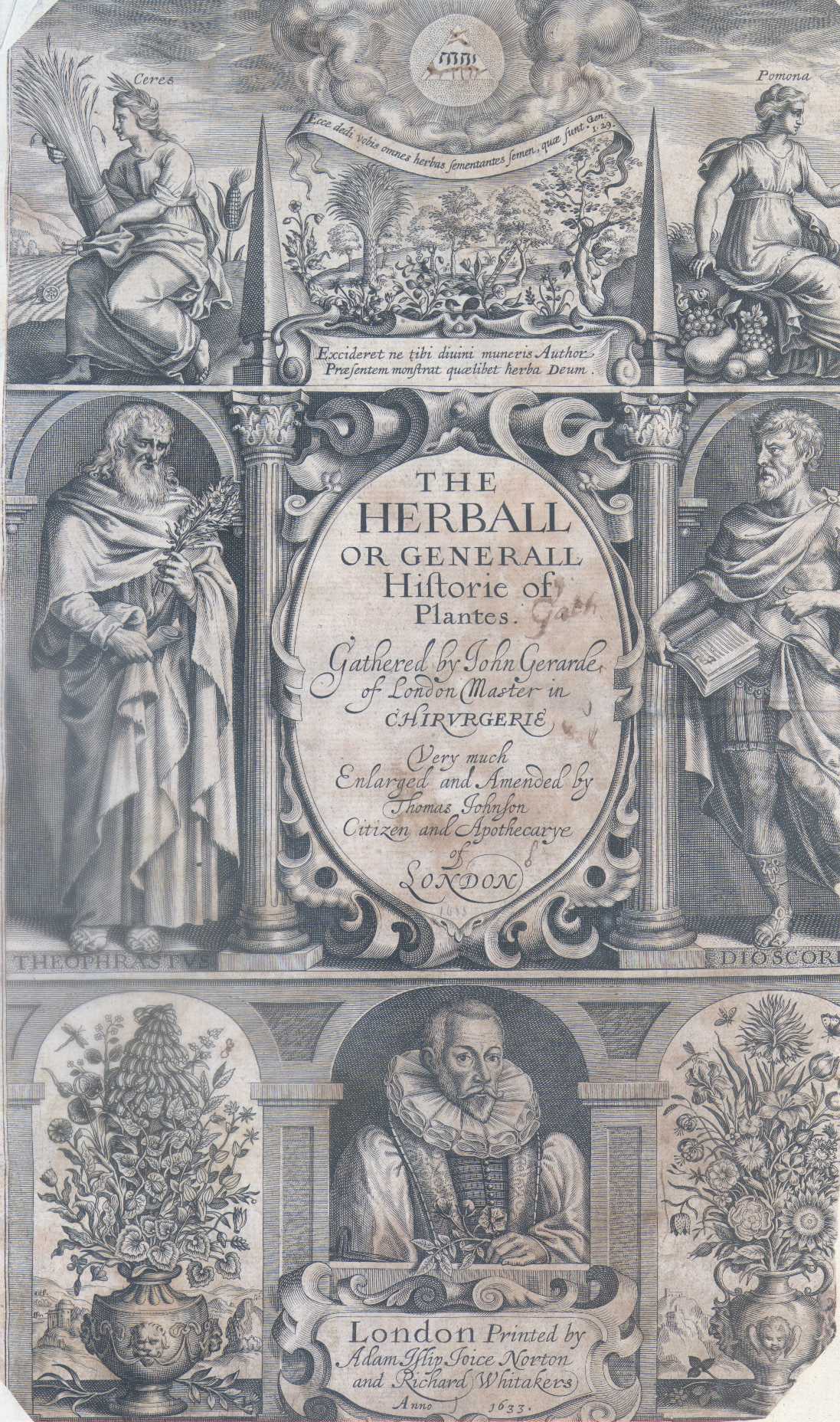

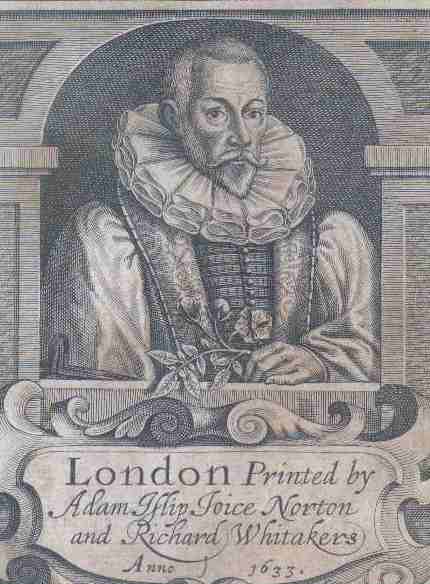

John Gerard (1545-1612)

The herball or generall historie of plantes

London, 1633

Gerard was the best known of all the English herbalists. His garden at Holborn contained over a thousand herbs, including many obtained from the New World. He claimed that tobacco could cure conditions such as migraine, toothache, gout, ulcers, asthma, and deafness. He does advise, however, that although smoking the dried leaves in a pipe may "palliate or ease for a time", it would "never perform any cure absolutely".

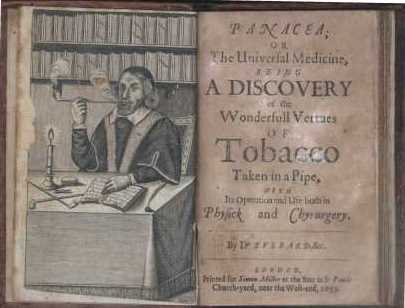

Giles Everard (16th century)

Panacea; or the universal medicine,

being a discovery of the wonderfull vertues of tobacco

London, 1659

Everard's work was first published in Latin in 1587. He added to Monardes' list of diseases to such an extent that tobacco came to be regarded by many as the great universal medicine. Everard even implied that it was such a cure-all that there would be less need for physicians. "It is no great friend to physicians, though it be a physical plant; for the very smoke of it is held to be a great antidote against all venome and pestilential diseases."

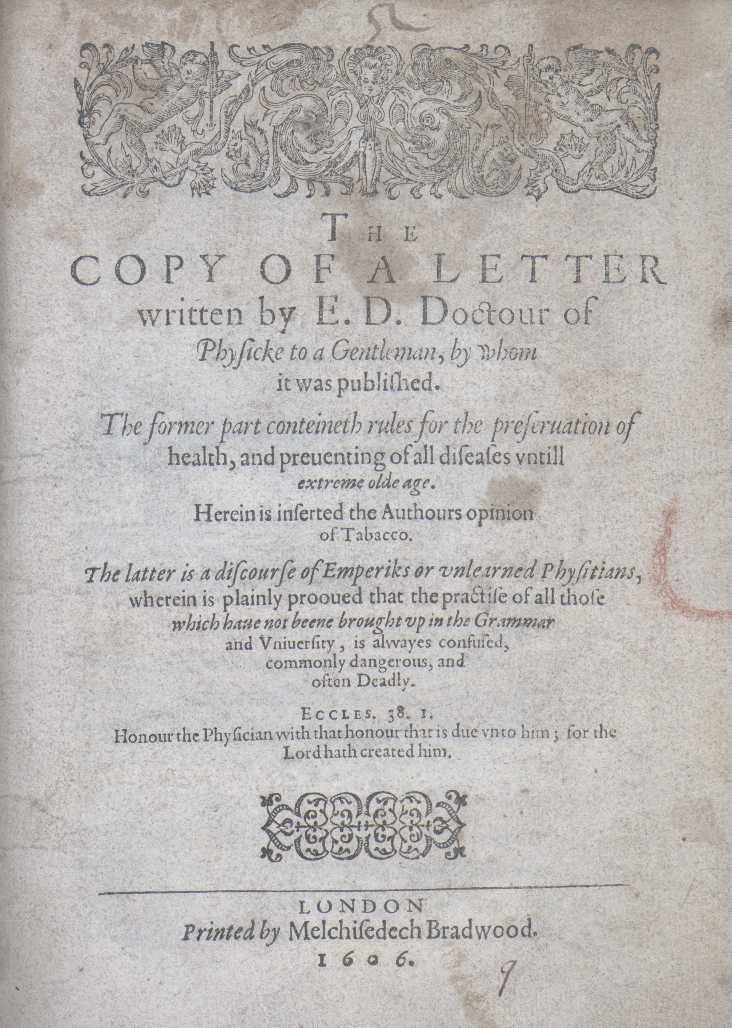

Eleazar Duncon the Elder (16th century)

Rules for the preservation of health

London, 1606

Duncon was one of the first physicians to write about the harmful effects of smoking tobacco. In his attack on quacks and unqualified physicians he warned, "Doth not tabacco then threaten a short life to the great takers of it?" He concluded with a special warning that it was "so hurtfull and dangerous to youth" that it might just as well be known "by the name of youths-bane, as by the name of tabacco."

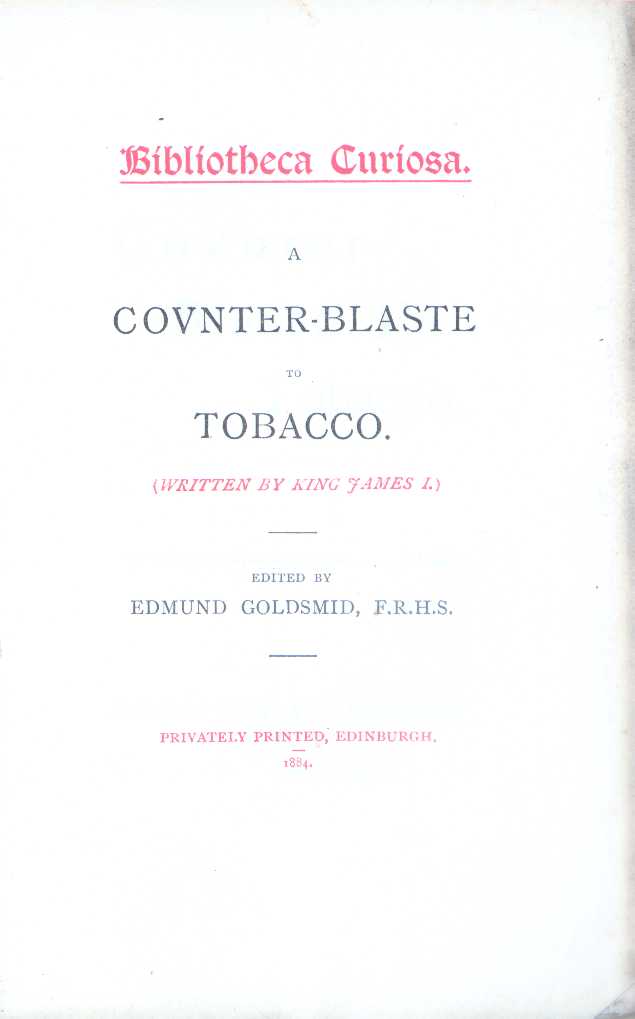

King James VI & I (1566-1625)

A counter-blaste to tobacco

Edinburgh, 1885 (Reprint of edition published at London in 1604)

The tobacco controversy became so heated that even the King became involved. James denied that "this vile custome" had any medical value whatsoever. By using logic, and the medical knowledge of his time, King James challenged many of the claims that were being made. "The filthy smoke", he wrote, "makes a kitchin also oftentimes in the inward parts of men, soiling and infecting them, with an unctious and oily kinde of soote, as hath bene found in some great takers, that after their death were opened." He also referred to its addictiveness whereby the smoker "is piece by piece allured" until he craves it like "a drunkard will have as great a thirst to be drunk." The King concluded with the view that it was "a custome lothesome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmfulle to the braine, dangerous to the lungs".

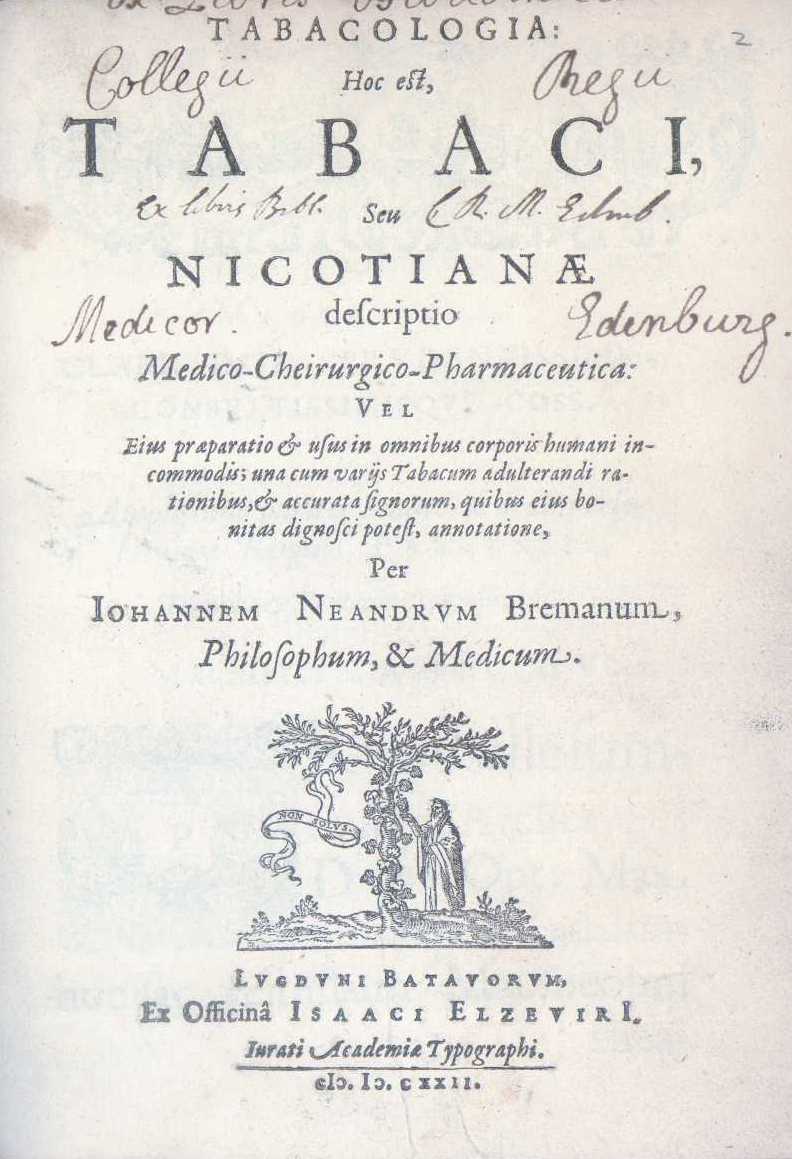

Johann Neander (ca. 1596-1630)

Tabacologia

Leyden, 1622

Neander compiled his information mainly from sixteenth century herbals. Although he recommended the medical use of tobacco in recipes, he warned against its recreational abuse. It was, he said, "a plant of God's own making, but the devil likewise involved; excesses ruined both mind and body." His work also contains the earliest known printed depictions of native Americans cultivating and curing tobacco.

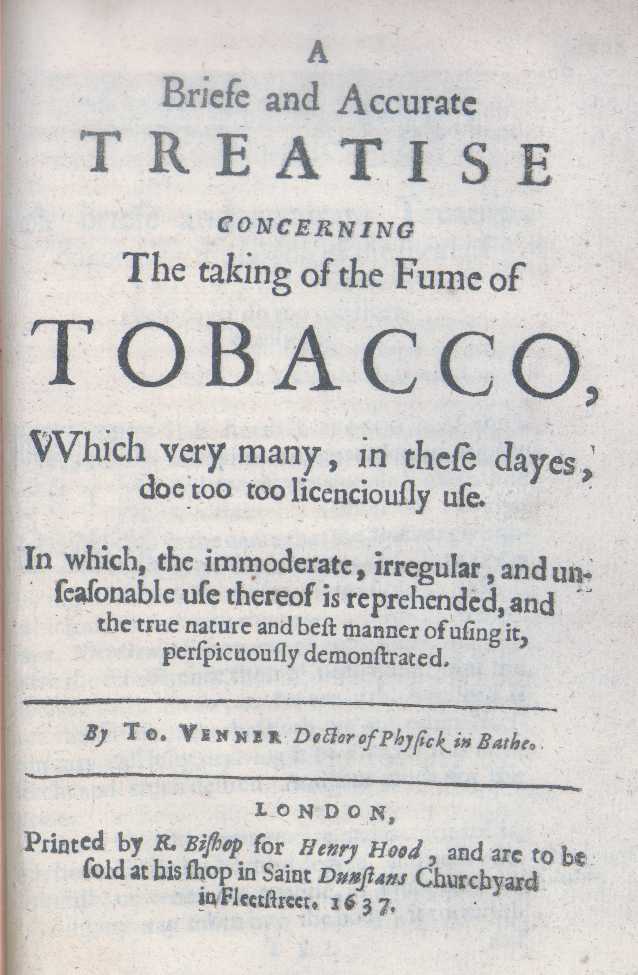

Tobias Venner (1577-1660)

A briefe and accurate treatise concerning the taking of tobacco

London, 1637

Venner's treatise on tobacco reveals the prevalence of tobacco smoking as early as 1621. Venner criticises those who "cannot travel without a tobacco-pipe at their mouth", as well as those who smoke between the courses at meals. He also warns that "this custome of taking the fume downe into the stomack and lungs" is "very pernicious." The lungs will "consequently become unapt for motion, to the great offence of the heart, and ruine at length of the whole body."

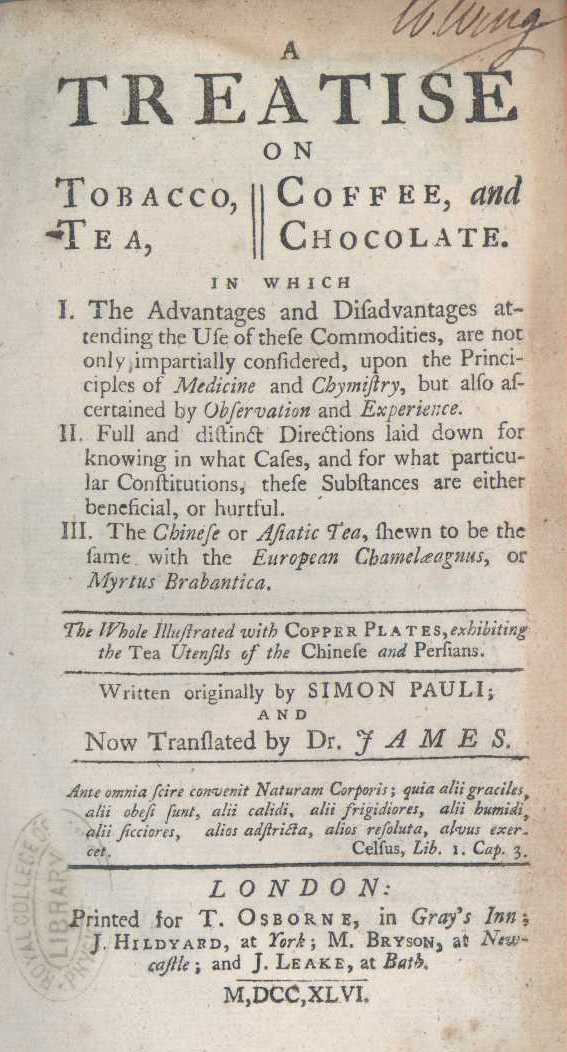

Simon Paulli (1603-1680)

A treatise on tobacco, tea, coffee, and chocolate

London, 1746

Paulli was a professor of botany, anatomy and surgery as well as physician to Christian IV of Denmark. A fierce critic of the smoking of tobacco, he marvelled at how Europeans could be “so infatuated and hood-winked” to purchase death at such a great price. He concluded “If any champion for tobacco should ask me whether I would have the Pope, the Emperor, and all the Kings, Electors, Princes, and Dukes in Europe, prohibit and discharge the use of tobacco? I answer, that such a revolution is really to be wished for”.

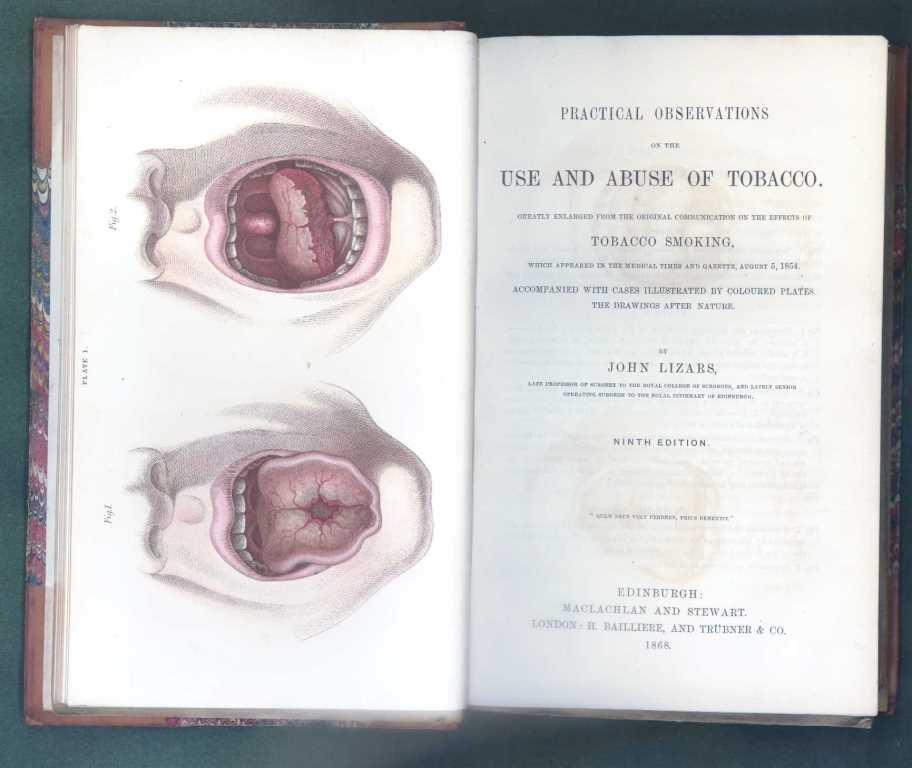

John Lizars (1787-1860)

Practical observations on the use and abuse of tobacco

Edinburgh, 1868

By the mid 19th century physicians had generally abandoned the idea of tobacco as the great panacea. John Lizars, Senior Operating Surgeon to the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, published his Observations linking tobacco smoking with cancer of the mouth and tongue. He warned “injury done to the constitution of the young may not immediately appear, but cannot fail ultimately to become a great national calamity”.

If you'd like to find out more, you can email us at library@rcpe.ac.uk

Follow our Twitter account @RCPEHeritage or our Facebook page or sign up to our newsletter to get notifications of new blog posts, events, videos and exhibitions.