The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were, for medicine, notable for their great plurality. There were all kinds of treatments on offer – healers, quacks, wise women, and itinerant sellers of all manner of cures. Orthodox medicine, however – practiced by trained and qualified physicians - was largely reserved for the elite. As hospitals were rare, and often more focused on spiritual wellbeing than medical treatments, wealthy folk were usually treated in their homes – either by a visiting physician, or via correspondence.

Which is partly why the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh’s decision, at its very first minuted meeting in 1682, to establish a Dispensary for providing medical services for the poor was so significant. This was to be the first ever free provision of medical services for the poor of Edinburgh, providing everyone with access to respected medical opinion and treatment. It was also the first free public dispensary in Britain.

Establishing a Dispensary

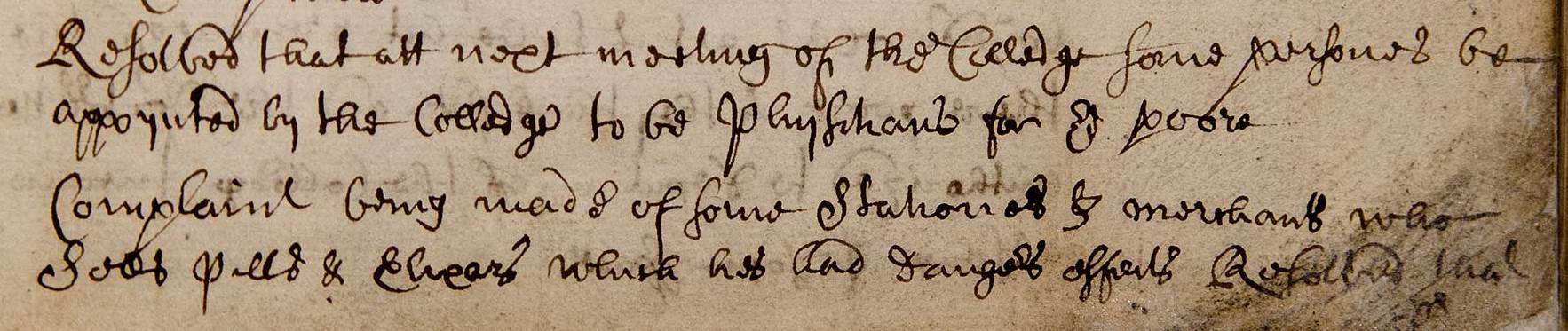

The College first resolved

‘that att the next meeting of the Colledge some persouns be appointed by the Colledge to be physitians for the poore’

(Extract from College Minutes)

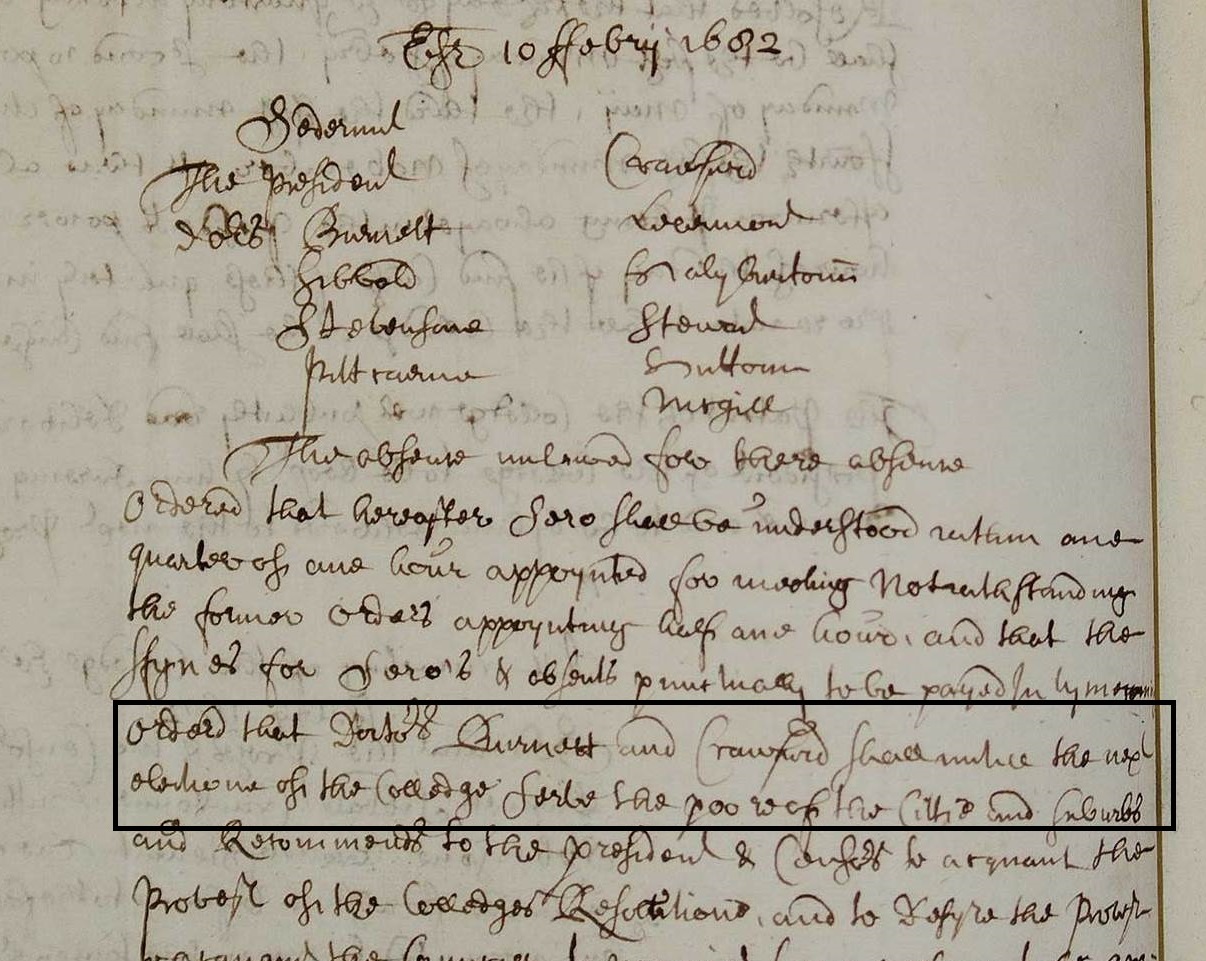

This determination continued into the next meeting, where it was decided that physicians would be appointed for a period of 12 months each, two at a time, to visit the poor and provide advice and treatment. It was

‘ordered that Doctors Burnett and Crawfurd shall until the next electione of the College serve the poore of the Cittie and suburbs’

(Extract from College Minutes)

Paying for the poor

The College physicians developed and maintained this service, contributing to the costs of medicines. This was done in part by the expedient measure of fining any doctors who failed to attend at their prescribed times to ‘the sick poore’. So any failure to provide a service in person was provided out of their pocket instead.

Later it was decided that fixed contributions to the Dispensary were to be paid by each Fellow on election to the College. This provided a much more stable and reliable stream of funding to support the service.

Expanding the service

In 1705, when the College moved into more ample premises, it was decided to provide an on-site rather than home-visit service, allowing them to treat many more patients.

‘unanimouslie agried…That tue of their number shall attend at their place of meeting every Munday Wedensday and ffryday betwixt thrie and four in the afternoon for givieing advice to the sicke and poore Gratis’

Treatment and cure

The treatment provided by this on-site Dispensary would have looked significantly different from its equivalent today. An emphasis at this time on bleeding and purging seems unlikely to have always been helpful. And while notions of the need for clean air and clean surroundings, as well as a healthy diet and lots of exercise, have a definite logic to them – they were perhaps less achievable for many of the poorer patients than for the more well-off clientele. Newer chemical and herbal remedies coming to the fore were more likely to provide a cure than the older traditional unicorn horns and weapon salve (where treating the weapon which had caused a wound was believed to cure the wound itself).

The new Royal Infirmary

(Site of Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, c.1729)

Later, when the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary was established in 1729, managers advanced a proposal

‘That in place of the Colledge their giveing attendance upon poor patients at their own hall twice a will be pleased in time Coming in their turn to attend the poor out patients at the Infirmary’

The Dispensary moved from the College to the Infirmary, but the principles and system of organising this service for the poor continued.