Elizabeth Blackwell, A Curious Herbal

(London, 1737-1739)

Elizabeth Blachrie was the daughter of a wealthy stocking merchant in Aberdeen. Her second cousin Alexander Blackwell was the son of Thomas Blackwell, Professor of Divinity at Marischal College, and Principal of the University between 1717 and 1728. By the age of fifteen Alexander is said to have become an accomplished Greek and Latin scholar. He then attended Marischal College where he became distinguished for his knowledge of the classics, and also studied French. According to one account it was during this time that he secretly married Elizabeth.

Alexander claimed that he then studied medicine under the great Hermann Boerhaave at Leyden. If he did so, it must have been for a relatively short period. By 1728, at only nineteen years of age, he and Elizabeth were living in London, where Alexander was working as a proof-reader. In 1730, financed by money from Elizabeth, he set himself up in his own printing business. Here things started to go horribly wrong.

Alexander claimed that he then studied medicine under the great Hermann Boerhaave at Leyden. If he did so, it must have been for a relatively short period. By 1728, at only nineteen years of age, he and Elizabeth were living in London, where Alexander was working as a proof-reader. In 1730, financed by money from Elizabeth, he set himself up in his own printing business. Here things started to go horribly wrong.

A combination of London printers brought an action against him for not having served an apprenticeship in the trade. The Blackwells were forced out of business, and in 1734 Alexander was declared bankrupt and committed to a debtors’ prison. According to the Bath Journal, Elizabeth then resolved “to extricate herself and her husband out of the difficulties they were fallen into”.

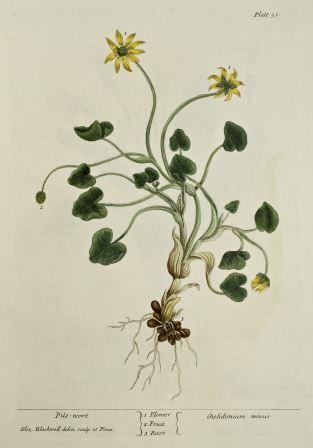

Elizabeth had learned that there was a great need for a herbal of medicinal plants. Encouraged by Sir Hans Sloane, then President of the College of Physicians of London, and Isaac Rand, the Director of the Chelsea Physic Garden, Elizabeth took lodgings close to the gardens and embarked on her great undertaking. The first step was the drawing of each plant as true to life as possible. The drawings were then taken to Alexander in prison where he supplied them with the scientific and foreign nomenclature. When a considerable number of the drawings were ready a team of nine eminent physicians, apothecaries, and a surgeon examined them, and declared in a ‘Publick recommendation’ their “good opinion of the capacity of the undertaker”.

Elizabeth had learned that there was a great need for a herbal of medicinal plants. Encouraged by Sir Hans Sloane, then President of the College of Physicians of London, and Isaac Rand, the Director of the Chelsea Physic Garden, Elizabeth took lodgings close to the gardens and embarked on her great undertaking. The first step was the drawing of each plant as true to life as possible. The drawings were then taken to Alexander in prison where he supplied them with the scientific and foreign nomenclature. When a considerable number of the drawings were ready a team of nine eminent physicians, apothecaries, and a surgeon examined them, and declared in a ‘Publick recommendation’ their “good opinion of the capacity of the undertaker”.

After finishing the drawings Elizabeth then set to engraving the illustrations on to the copper plates. On the return of the printed sheets this “virtuous and  worthy” woman set about hand colouring each and every page of every issue ready for binding and publication. Originally published in weekly parts, the first collected volume of 'A Curious Herbal' appeared in 1737, with the second being issued either in late 1738 or early 1739. In total it consisted of five hundred illustrations drawn, engraved and hand coloured by Elizabeth Blackwell herself. The ‘Curious’ of the title, is from an archaic use of the word, meaning ‘accurate and precise’.

worthy” woman set about hand colouring each and every page of every issue ready for binding and publication. Originally published in weekly parts, the first collected volume of 'A Curious Herbal' appeared in 1737, with the second being issued either in late 1738 or early 1739. In total it consisted of five hundred illustrations drawn, engraved and hand coloured by Elizabeth Blackwell herself. The ‘Curious’ of the title, is from an archaic use of the word, meaning ‘accurate and precise’.

The finished work met with the approval of both the College of Physicians and the College of Surgeons, and the whole enterprise proved such a success that it restored the Blackwells’ finances. Alexander was released from prison after serving two years, a young man apparently with a promising future ahead of him. There was, however, more trouble and tragedy still to come.

Alexander took up a new career as an agricultural adviser, and for a time worked for the Duke of Chandos as director of the aristocrat’s improvements on his estate of Canons in Middlesex. In 1741 he published an agricultural textbook, A new method of improving cold, wet and barren lands.

Things seemed to be going well. In 1742, on the recommendation of the Swedish ambassador in London, Alexander went to Sweden where he continued his work on agriculture and added the profession of physician to his repertoire. In 1744 he gained the patronage of King Frederick, and was awarded a royal estate where he could carry out his experiments of agricultural improvements.

Unfortunately Alexander then turned his hand to politics. The intrigues of the time now make the truth of the whole affair difficult to establish. The aftermath of the Forty-Five rebellion had led to links between the Jacobites and some highly-placed individuals in Sweden, and there were contending factions under French and Russian influences. It certainly was not the best of times for someone like Alexander. He is reported to have had “a very indiscrete licence of tongue … against persons in power.“

Alexander Blackwell was accused of being involved in a plot to alter the Swedish succession; he was arrested and subsequently condemned for high treason. He was executed on the 29th of July 1747, showing it is said, remarkable fortitude. After attempting to lay his head on the wrong side of the block he apologised on the grounds that it was the first time he had ever been beheaded.

Alexander Blackwell was accused of being involved in a plot to alter the Swedish succession; he was arrested and subsequently condemned for high treason. He was executed on the 29th of July 1747, showing it is said, remarkable fortitude. After attempting to lay his head on the wrong side of the block he apologised on the grounds that it was the first time he had ever been beheaded.

Elizabeth was at least spared witnessing her husband’s death. She was in England at the time, apparently just on the point of joining him in Sweden when the tragedy occurred. Little more is known of Elizabeth Blackwell apart from the simple facts that she died in 1758 and was buried in the churchyard of Chelsea Old Church. Her great work remains, however, each page a testament to a remarkable woman. “As a monument of female devotion it is most touching and admirable, and its practical value was very great.”