The Federation of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the UK has provided international UK equivalent Core Medical Training (CMT, now Internal Medicine Training, IMT) since 2015. The quality management of these international programmes includes externality at the Annual Review of Competence Progression (ARCP) and an accreditation process. This paper describes the use of a short trainee questionnaire to support the accreditation process.

The history and delivery of UK equivalent Core Medical Training has been previously described.1,2 It is currently delivered in six sites (Iceland; Kochi, Trivandrum and Wayanad in Kerala; New Delhi; and in Dubai in the Middle East). To ensure UK equivalence, a considerable programme of training is put in place for both trainers and trainees before the programme starts. Once running, externality is provided each year at the ARCP and a process of accreditation based on relevant international standards of education is delivered every two to three years.3

In the UK, the process of quality management of training posts and programmes is undertaken by regional postgraduate deans and to support it, since 2010 there has been a UK-wide General Medical Council (GMC) run questionnaire which is completed by over 95% of all trainees in the UK each year.4 This has developed significantly since 2010 and questions are reviewed in detail with regard to relevance for individual specialties on an annual basis. The survey itself was based on historical surveys that had been developed in a number of deaneries, including London, and Kent, Surrey and Sussex. The survey represents a subjective view of the trainee’s experience in each post and programme and its power is in comparative responses with other posts and programmes and how those responses change over time. Many postgraduate deans pay particular attention to outlying issues compared with the rest of the UK and where those issues persist over time. The great strength of the survey is when it is used by local educational leaders to question and challenge educational and service practice and thus improve both the care of patients and training. To support physicianly training, the Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board (JRCPTB) provides its own analysis based on the published GMC data of particular relevance to heads of schools of medicine and training programme directors who are running the CMT (now IMT), as well as higher specialty training programmes.5 This comparative analysis focusing on physician specialties is well received as a useful supportive tool at a local level to make improvements and challenge practice. It is also a fundamental part of The State of Physicianly Training report that is published by the Federation every two years.6

The current GMC survey is long and designed to cover all aspects of UK training and practice. It would therefore not be appropriate to simply use it in an international accreditation process. However, anonymous trainee data was thought to be a useful tool to support the Federation international accreditation process. Most importantly to help identify quality issues, but in part, to give some impression of trainees’ subjective views internationally, compared with their colleagues in the UK. Therefore, a much smaller survey tool was designed to be able to be used internationally but also to offer some comparison with current UK GMC trainee responses. As the international CMT programme is designed to be UK equivalent, it was important that the questions used were essentially unchanged.

Methods

Each year the GMC agree with JRCPTB the questions for the annual UK trainee survey (108 in total in 2019). This long set of questions cover many issues that only have relevance to the UK such as rota gaps. It also includes a comprehensive set of 18 additional questions to provide a summary of the published CMT quality criteria.7 This full question list would not have been appropriate for international programmes. So, a subset of questions was identified that would work in an international context, were relevant to the provision that we were trying to provide, broadly sampled quality issues in the whole curriculum, and were questions that experienced visitors routinely used in practice.

Through this process, an initial set of 17 questions was identified. These were then discussed with senior quality administrators within JRCPTB and at wider clinical engagement groups within JRCPTB, with wide diversity and experience of international training, to produce a final list of 18 questions (Table 1). The questions were then reviewed for an international context with one partner. The final set agreed were very similar, but not absolutely identical in wording, with those in the GMC survey to ensure they worked when built on to a very simple survey monkey questionnaire.8

Table 1 Final list of 18 questions

|

|

|

1

|

Please confirm your current year of training. (International sites only)

|

|

2

|

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement? I am confident that I know how, or could find out how, to raise a concern about my education and training. (Educational governance)

|

|

3

|

In this post, OUT OF HOURS, how often (if ever) are you expected to obtain consent for procedures where you feel you do not understand the proposed interventions and its risks? (Clinical supervision out of hours)

|

|

4

|

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements? Handover arrangements in this post always ensure continuity of care for patients BETWEEN SHIFTS. (Handover)

|

|

5

|

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement? I’m confident that this post will give the opportunities to meet objectives set out in my development plan relating to: CLINICAL EXPERIENCE (for example examination skills, taking a history, deciding investigations and management, seeing a variety of patients in different settings etc.). (Curriculum coverage)

|

|

6

|

Have you received feedback in a formal meeting with your educational supervisor about your progress in this post? (Feedback)

|

|

7

|

In this post, how often (if ever) are you supervised by someone who you feel isn’t competent to do so? (Clinical supervision)

|

|

8

|

How would you rate the intensity of your work, by night in this post? (Workload)

|

|

9

|

In this post, how often (if ever) do you feel forced to cope with clinical problems beyond your competence or experience? (Clinical supervision)

|

|

10

|

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement? My educational supervisor is easily accessible should I need to contact them. (Educational supervision)

|

|

11

|

Please rate the quality of teaching (informal and bedside teaching as well as formal and organised sessions) in this post. (Overall satisfaction)

|

|

12

|

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement? Staff, including doctors in training, always treat each other with respect. (Supportive environment)

|

|

13

|

Please rate the quality of the induction you received for this post. (Induction)

|

|

14

|

How would you rate the practical experience you were receiving in this post? (Adequate experience)

|

|

15

|

How would you describe this post to a friend who was thinking of applying for it? (Overall satisfaction)

|

|

16

|

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement? This post will be useful for my future career. (Overall satisfaction)

|

|

17

|

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement? My organisation encourages a culture of teamwork between multidiscipline healthcare professionals (for example nurses, midwives, radiographers etc.). (Teamwork)

|

|

18

|

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement? My organisation encourages a culture of teamwork between clinical departments. (Teamwork)

|

International partner sites were then invited to contribute to this process as part of the quality management process of the quality management system for these international training sites.

Once permission was received, all trainees received a letter about three months before the survey informing them about it, including the UK experience. It emphasised the importance of contributing to the survey while confirming the guaranteed anonymity of all responses. The actual survey was then circulated by email through the local administration, but all responses went directly back to JRCPTB. After two weeks, a general reminder was sent to all trainees, again via the local office, where the response had not yet been 100%.

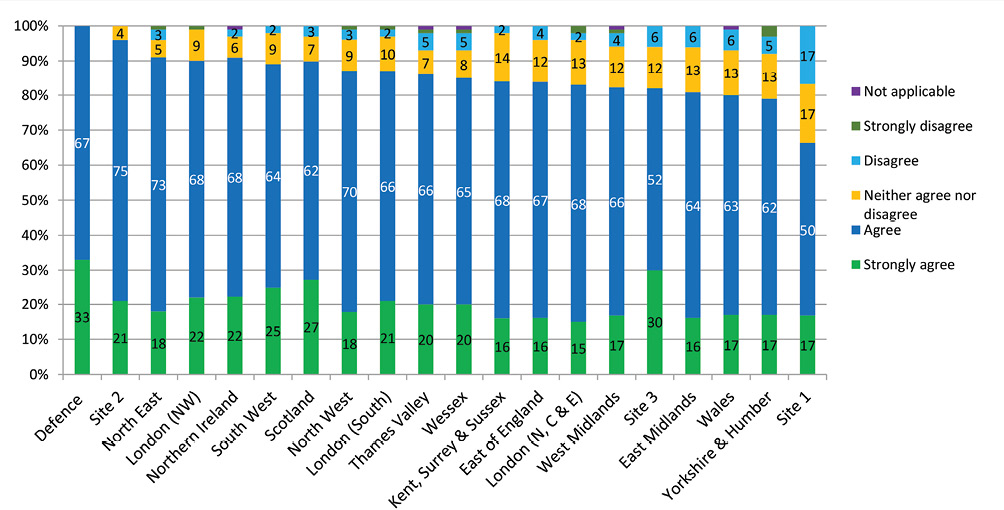

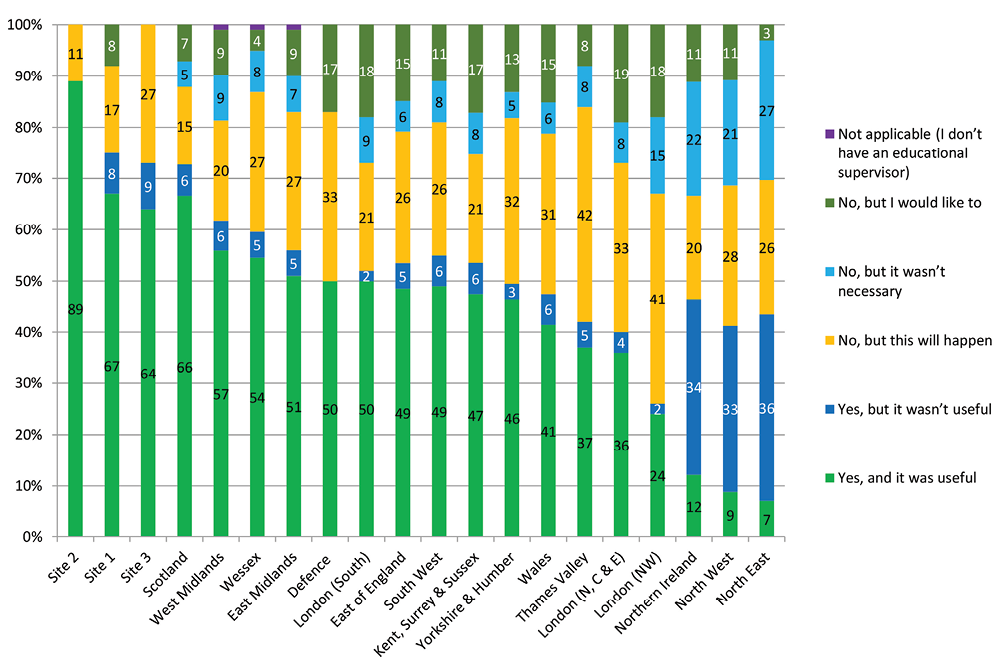

Once the survey was closed, JRCPTB undertook an analysis showing how the responses, in each of the international sites, compared with the 2019 results in the UK, by deanery. This document was then returned to each international site with a request to circulate it widely to all trainees and trainers.

Results

We describe the results of this process for the first three of the current six international partners of JRCPTB: one site in Iceland and the other two in India. In site one, 12 of 12 (100%) completed the survey. In site two, 28 of 30 (93%) and in site three, 36 of 38 (95%) completed the survey. No problems with question understanding or difficulties with the technology were reported.

In the first pilot site one, a private and confidential face-to-face discussion with all the trainees and a UK accreditation team occurred shortly after completion of the questionnaire. This generated positive comments about the survey and useful discussion about quality issues. For example, at that site an issue with consent was identified through the survey which senior management and supervisors had not been aware of. In the other two sites, the information was fed back and discussed with trainees and supervisors in local meetings.

The data are presented graphically with the international sites compared for illustration, with the UK deanery responses in 2019 as analysed by JRCPTB. All results were found to be reasonably comparable to UK responses. No important negative outliers were identified. For the time being we believe it is appropriate that the international sites remain anonymous (although they know which are their set of results).

The full set of graphical comparative tables are available online from the JRCPTB.9 For illustrative purposes, four examples are set out in this paper (Figures 1–4).

Figure 1 To what extent would you agree or disagree with the following statement? I am confident that I know well, or could find out, how to raise a concern about my education and training.

Figure 2 In this post, out of hours, how often (if ever) are you expected to obtain consent for procedures where you feel you do not understand the proposed interventions and risks?

Figure 3 Have you received feedback in a formal meeting with your educational supervisor about your progress in this post?

Figure 4 How would you describe this post to a friend who is thinking of applying for it?

Discussion

We successfully implemented a short online trainee survey to support the quality management of the Federation’s UK equivalent CMT programmes. The survey samples across the generic standards for postgraduate education that we use for the Federation accreditation process3 and provides useful further input into that process.

There was good trainee engagement, and the survey could be operated remotely and anonymously from the UK. The very close similarity of questions with questions in the national GMC survey allowed easy relative comparison in a graphical format that was readily accessible by both trainees and trainers. Experience at all three sites found that the information was subsequently used for quality discussions with both trainees and trainers.

As in the UK, we found considerable variation both between the international sites and the UK experience. This was neither consistently good or bad and no serious issues requiring immediate intervention were discovered that would compromise the safe delivery of training. Importantly for the longer-term success of the programme, there was considerable evidence of trainee satisfaction with their supervision, the quality of teaching, overall satisfaction, and whether the post would be useful for a future career. As in the UK, there could be specific challenges around consent for procedures and supervision out of hours.

Although each item can be compared graphically with UK deanery results, we do not produce a league table, although to give some guidance we do, as in the UK, report overall quartiles.5,9 However, it is not appropriate to produce a league table as we are only sampling a small number of questions, the individual questions are not comparable to each other in terms of their importance, and the questions may have very different spreads of results. The main learning to take from the results is the importance of having an opportunity for an informed and engaged discussion at the local level about both service and training delivery and as a basis to look at trends over time.

As with any survey tool, it has its limitations. It is based on a subset of questions from the full UK questionnaire to make it both acceptable and yet still useful for quality management purposes. It needs to be deliverable in a number of international sites and short enough to ensure good engagement with the process from the start. Evidence from the first sets of results and site visit suggests that it does meet its objective of supporting quality management processes and provides some reassurance, but not directly comparable evidence, that the training is meeting its aim of being UK equivalent. Full confidence in the process, especially confidentiality, is likely to come with repeat usage as indeed happened in the UK.

In summary, we have shown that a simple online questionnaire can have good engagement with trainees on an international basis and produce useful information that helps trainees and trainers discuss the care of their patients and improving training. It also supports the Federation accreditation process of the six current UK equivalent CMT (now IMT) programmes.