In the winter of 1494–1495, King Charles VIII of France laid siege to the city of Naples. With the (ultimately temporary) French victory, the majority of the soldiers and mercenaries began to withdraw from the siege and proceed to their homelands, which included Italy, France, Germany and Scotland. As the militaries moved through the Italian peninsula, contemporaries began to notice the appearance of a strange sickness. The illness spread very rapidly, reaching Scotland by 1497, India by 1498, Russia by 1500, and China by 1505.1 The most commonly recorded symptoms were severe pains in the joints and limbs along with outbreaks of pustules, boils, and other ‘festering or hardened eruptions of the skin’.2 In its most horrific form, the disease rotted the bones and skin of its living victims, devouring, amongst other things, noses, penises, and leg bones.2,3 One Germanic witness (and later victim) of the disease, Joseph Grünpeck, a secretary to the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, recorded in 1496 that the pain it caused was so extreme that those infected ‘wished to die as soon as possible’.4

The pox

The disease became known by several names, including ‘grandgore’ (Scotland), ‘great pox’ (France), and ‘French pox’ (Germany and Italy). Here I use the term ‘French pox’ (also abbreviated to ‘pox’) because this is the most accurate translation of the language in the primary sources in which this article is founded. While this paper focuses on the period 1495–1560, many would argue that the French pox is alive and, indeed, thriving today as the disease known as syphilis. Many historians, including Claude Quétel and Robert Jütte, have used the term ‘syphilis’ to refer to the disease that pervaded in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe.5,6However, this article follows scholars including Claudia Stein, Laura J. McGough, Jon Arrizabalaga, John Henderson and Roger French in using an early modern name for the disease when studying this era.2,3,7 As Stein argues, a principal reason for using a contemporary name is that a disease is ‘a socio-cultural construct specific to a particular scientific and socio-cultural setting at a given time’.2 Consequently, the use of an early modern name helps to separate our current medical and cultural understandings of the disease from those of the past. For example, interpretations and cultural meanings of the pox in the early modern period were deeply influenced by contemporary theories of morality which constructed many (but not all) cases of the disease as God’s punishment for sinful behaviour, including not only sexual sins but also other immoral actions such as blasphemy.8 Meanwhile, the term ‘syphilis’ is strongly associated with the nineteenth- and twentieth-century ‘syphilis hysteria’ that pervaded in western countries. This was a governmental, medical, and societal anxiety concerning the threat that syphilis was perceived to pose to the physical and moral wellbeing of the individual, family, and state. These attitudes resulted in the strict regulation and stigmatisation of prostitution in Germany and other western countries.2 Therefore, using a contemporary term helps us to focus on the disease in a particular historical moment.

A new type of medical practitioner: indispensable, competitive, and suspect

This paper sheds light on a heretofore largely uninvestigated category of medical practitioners: the Franzosenärzte (French pox doctors, singular: Franzosenarzt). This new type of medical practitioner, who emerged in the German-speaking lands of the Holy Roman Empire during the final years of the fifteenth century, provided essential and highly valued care for victims of the French pox. Until now, very little has been written on the Franzosenärzte. Research has been situated within larger projects, including Stein’s study of medicine and the French pox in Augsburg; Karl Sudhoff’s collections of French pox regulations from Nuremberg; and Paul Uhlig’s studies of the pox and medical practitioners in Zwickau.2,9–13The absence of dedicated studies reflects the difficulties of tracing these practitioners in the archives. Although the Franzosenärzte played a key role in treating the pox, they left little trace in sources. We are yet to uncover the writings of any such practitioner, and mostly find our information through much searching in municipal records. Through an exploration of Nuremberg’s fifteenth- and sixteenth-century municipal records, this paper makes a first step in filling this gap in the historiography, focusing particularly on the position of the Franzosenärzte within the city’s medical and civic systems.

Building on this analysis, this paper argues that in Nuremberg the Franzosenärzte were simultaneously indispensable, competitive, and suspect practitioners. At a moment when the city’s trusted official physicians were unable to aid those suffering in the city, the Franzosenärzte arrived, bringing hope with their promise of effective treatments. Nevertheless, the city’s civic authorities and medical practitioners kept a close watch over the French pox doctors. The council constantly feared that their citizens would fall prey to profiteering quacks, while the surgeons and physicians jealously guarded their stations within Nuremberg’s emerging medical hierarchy. For approximately 60 years, the Franzosenärzte carved out a profitable and respected role in Nuremberg; however, after 1557, these practitioners disappeared from the municipal records. As physicians took greater control of the medical marketplace and, along with surgeons, developed standardised pox treatments, and Nuremberg entered a period of financial strife, the Franzosenärzte lost their position as essential practitioners.

Setting the scene

During the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, Nuremberg was one of the largest cities in the Germanic lands, with estimates placing the population between 22,000 and 40,000 (circa 1500).14,15 At this time the city was enjoying its golden age, a period that saw a thriving economy and an outpouring of artistic, humanist, and scientific production, including artwork by Albrecht Dürer, humanist writings by Willibald Pirckheimer, and the production of the oldest surviving globe pioneered by Martin Behaim. As a free imperial city, answerable only to the Holy Roman Emperor, Nuremberg was governed by its Rat (city council), at the core of which sat the Innere Rat (inner council), which held the legislative power. Thirty-four of the inner council’s 42 seats were reserved for the city’s patriciate, a group of large-scale merchants and manufacturers with significant economic power and socio-cultural capital.16 The council sought to regulate almost every aspect of life within the city’s walls.15,17 During the sixteenth century, it extended its control considerably; this included developing its management of the healthcare and poor relief systems, as well as enforcing stricter moral standards on its population. As Gerald Strauss concluded, ‘(i)n Nuremberg… the Council was not merely the supreme authority, it was the only authority’.15

The arrival of the pox

On 2 September 1496, the inner council recognised the arrival of the French pox in Nuremberg; they recorded in their minute book (Ratsverlässe) that ‘the sickness called French evil’ was ‘to be cared for by the learned doctor[s] [of the] council’.18At this time, many believed that the French pox was a highly contagious disease, a stance supported by its rapid spread around Europe and the globe. Authors of medical tracts from the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries warned that the pox spread through a variety of mechanisms including sexual contact and ‘travels through external things’, such as eating utensils, money, food, and surgical instruments.19–22Nuremberg’s council also believed that the pox was a highly contagious disease with multiple transmission mechanisms. Soon after the official recognition of the disease in the city, the council launched an investigation into the possible transmission of the pox through pig meat.18 In October 1496, they ordered all afflicted citizens and inhabitants to proceed to the hospital of the Heilig Kreuz (Holy Cross), located outside of the city walls.18 This recalled the practice of removing plague victims to extramural locations which began in late fourteenth-century Italy and was subsequently adopted across Europe. Further, the Nuremberg council banned sick beggars from public places, such as bridges and streets, and any infected itinerant beggars who did not have residency rights in Nuremberg were to be expelled from the city.18 Clearly, Nuremberg’s council was anxious to control the spread of the illness and protect its healthy population.

Searching for a cure

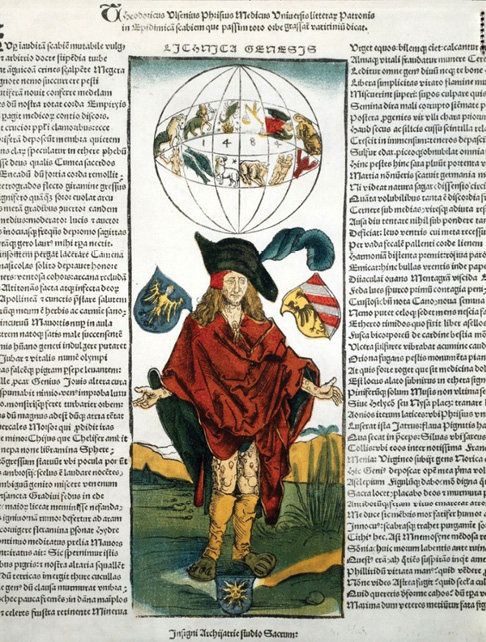

Anxieties prevailed not only about containing the disease but also curing it. During the late fifteenth century, many feared the French pox was incurable.3 This was reflected by Theodoricus Ulsenius, a Dutch municipal physician and humanist working in Nuremberg when the pox first appeared there, and one of those consulted by the council.23 In August 1496, Ulsenius’s Latin poem In Epidemica[m] scabiem (‘In the Scabies Epidemic’) was published as a broadsheet with a woodcut depicting a poxed individual (Figure 2). In this poem Ulsenius described how the new epidemic was raging but ‘nobody knew how to cure it’.24,25 While victims suffered in agony, he writes, the physicians argued incessantly amongst themselves but moved no closer to a cure.

Figure 2 Theodoricus Ulsenius, ‘Vniuersis littera[rum] Patronis’.

In: Epidimica[m] scabiem (Nuremberg, 1496). Source: Wellcome Collection. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/pt87tf6m. Licence: CC BY 4.0.

Despite the possibility that they were facing an incurable disease, the Nuremberg council did not only seek to protect the healthy; they also strove to aid the sick. These efforts were founded in ideas of good government, charity, and genuine sympathy for the sick; as well as the practical desire to heal the infected so that they or their families did not become permanently dependant on aid from the council.22In 1496, the council ordered that the city’s official physicians were to examine a recipe for a pox cure.18 In 1497, for the first time, Nuremberg’s municipal records documented the presence of a medical practitioner who specialised in treating the French pox; the council ordered that ‘The doctor of the French evil to be accepted as a citizen and granted the corresponding legal status of citizenship’.18 By this time the council had been contending with the French pox for over a year. Furthermore, by January 1497, the Heilig Kreuz hospital was overflowing with pox patients.18 Therefore, practitioners who specialised in treating this disease were valuable acquisitions for the city because they could relieve suffering citizens and ease some of the strain on the municipal healthcare system. Medical practitioners not born in Nuremberg, including the city’s esteemed official physicians (Stadtärzte), were not automatically entitled to citizenship. For example, one Stadtarzt, Heinrich Wolff swore his oath to the council in 1553 but did not receive citizenship until 1561.14 The relatively rapid grant of citizenship to the ‘doctor of the French evil’, indicates just how greatly the city trusted, esteemed, and needed this practitioner.

The proliferation of pox healers

By the first years of the sixteenth century, practitioners specialised in treating the French pox were proliferating in German-speaking regions. Augsburg’s city council employed several healers, who Stein describes as ‘French pox specialists’, to treat the sick in the municipal pox hospital (Blatterhaus). At the start of the sixteenth century, one of these healers, Johannes Wurzel from Friesland, was contracted to work there full time for 26 Gulden per quarter.2 By 1513, there were at least four Franzosenärzte working in Nuremberg. Employed by the council, they treated the poor in the municipal pox hospitals.18 By 1522, Zwickau’s council had also hired a Franzosenarzt to treat the city’s poxed poor.11 A council document preserved in Nuremberg’s Stadtarchiv (City Archive) outlines the principal duties and regulations placed upon the Franzosenärzte who gained permission to practice in the city. Probably composed between 1523 and 1543, these decisions outline that, in addition to the city’s physicians and surgeons, the council would also pay a ‘frazos[en] arzt’, who would care for the pox victims under municipal care, housed in the St. Sebastian plague hospital.26

All of the Franzosenärzte that I have encountered in my research were male, and at least eight of those who practised in Nuremberg came from outside the city. Unfortunately, the council records usually do not document their geographical origins, simply describing them as ‘foreign’. One came from Lindau in 1518 and another from Prague in 1539.18 The latter was still practising in Nuremberg in 1540, when he requested citizenship.18 However, many pox specialists were likely quite mobile, travelling to where there was a demand for their services. Zwickau’s council permitted its Franzosenarzt to travel in search of work when the pox subsided in the city.11The Nuremberg council limited some grants to practice in the city to fixed periods of a few months.18 Such permits allowed the council to assess further the practitioner’s performance and, as rates of the pox could fall significantly, these contracts ensured that the council was not paying for unused services.

Qualified or quacks?

Unfortunately, we are yet to uncover any Franzosenarzt’s records of their treatments, training, and understandings of the pox. Similarly, sources, such as physicians’ texts and municipal records, have so far been silent on the pox doctors’ specific treatments and techniques. The extant records relating to Nuremberg also lack any insight into how these practitioners gained their understandings of the French pox or how they came to the career of Franzosenarzt. However, some things can be established about the Franzosenärztes’ training. Unlike physicians and surgeons, who treated patients with a broad range of illnesses and health problems, the Franzosenärzte were dedicated to treating the French pox. In further contrast to the Germanic physicians, and some surgeons, it is unlikely that the Franzosenärzte possessed a university education. Instead, they probably underwent a training process similar to the regular surgeons and barber-surgeons (Wundärzte and Barbiere). Uhlig similarly concludes that the Franzosenarzt in Zwickau had training equivalent to that of ‘a field surgeon’.13 Thus, in the eyes of their contemporaries, the Franzosenärzte were ‘empirics’, a term denoting practitioners with a training and knowledge that ‘was hands-on and local’.14 This category also encompassed many ‘specialists’, who were dedicated to certain illnesses, areas, or types of treatment, such as eye doctors, teeth doctors, and bone breakers. While some of these practitioners established themselves in a location, others travelled from place to place. In Nuremberg, and across the German-speaking lands, many of these empirics and specialists were seen as important to the general health of the citizens, and many ‘exalted’ their practice.14 In Zwickau, for instance, the city council praised one such travelling practitioner for healing facial disfigurements. Furthermore, in 1539, they passed a regulation obliging their valued Franzosenarzt to seek the council’s permission if he wished to leave the city for any period to treat patients elsewhere.13 However, some of these empirics and specialists were regarded with suspicion. Citizens and government feared unlicenced quacks, selling dud cures, and they were frequently derided as incompetent, exploitative, and even dangerous. Itinerant specialists were often regarded with particular caution.14

As Hannah Murphy has demonstrated, it was during the sixteenth century that Nuremberg’s physicians gained authority over the city’s medical marketplace.14,27 However, the physicians did not secure their position at the peak of the medical hierarchy in Nuremberg and other Germanic cities like Ulm and Augsburg, until the second half of the century. The Empire’s medical marketplace was heterogeneous, valuing the skills of a range of practitioners, including physicians, surgeons, and empirics.28 In Nuremberg, there was intense competition. Murphy has shown how the surgeons and, especially the physicians and apothecaries, fought to establish which practitioners had the most understanding and experience.14

Pox politics

The arrival of the Franzosenärzte coincided with the early stages of the physicians’ efforts to rise to dominance. With Ulsenius and his fellow physicians struggling to explain and treat the pox, the Franzosenärzte, with their specialisation and their treatments which were considered effective by the council, undermined the physicians’ efforts to secure their place at the top of Nuremberg’s medical hierarchy. In retaliation, some physicians publicly derided the Franzosenärzte. For example, in 1497–98 two Augsburg physicians, father and son Johann and Ambrosius Jung, lamented that ‘unqualified quacks’ were selling a mercury salve at extortionate prices, without any heed to the individual nature and condition of the pox victims that came to them.2In the early seventeenth century, Tobias Knobloch, a city physician of Ansbach and personal physician of the Princess of Brandenburg, wrote in his De lue venerea (‘Of the Venereal Disease’) that Franzosenärzte routinely stripped the sick of their money and their health.21 Nevertheless, the Nuremberg council’s grants of permission for Franzosenärzte to practice in the city clearly illustrates that they ratified them as skilled and effective practitioners.

However, the physicians’ objections and slanders, along with popular anxieties about quacks, also permeated the council’s governance. They constantly sought to uncover practitioners who had no medical training or education but who, regardless of this, produced and sold remedies ‘through which the common man loses not only his money, but also his health suffers great damage and cannot recover’.29 The council’s vigilance was not unwarranted, as seen in 1518, when a Nuremberg citizen was discovered to be pretending to be a Franzosenarzt and banned from practising.18

Hierarchy

Despite the council’s recognition of the skills of the Franzosenärzte, the physicians and, below them, the surgeons ultimately secured their dominance. During the sixteenth century the role of municipal physician was legally encoded in cities across the Empire, providing an official position. Furthermore, sumptuary regulations granted physicians many privileges of the nobility. Their role located them between the burghers and the elites and many physicians came from great and good families, while others married into the patriciate, further increasing their influence and social status.14 Furthermore, they used their university educations to distinguish themselves from ‘artisanal’ healers like barber-surgeons and place themselves amongst the learned elite.28 In contrast, Nuremberg’s apothecaries, who once held quite important civic positions, patronising artists and mixing with the patriciate, were moved to a lower standing. Legislation lessened their hold on property and their professional standing became ‘a mercantile-like attachment to tools and instruments’.14 Moreover, unlike the physicians, apothecaries were not hired by the council. The physicians had the legal and social leverage required to ensure their position. Meanwhile, it appears that the Franzosenärzte, like most other specialists and empirics, came from lower in the social scale and thus lacked these influential connections.

Regulating the Franzosenärzte

To gain their permits to practice in Nuremberg, the local and ‘foreign’ (from outside the city) Franzosenärzte had to undergo an examination assessed by the city’s sworn physicians and surgeons. Permission to practice was not simply granted on the basis of claimed qualifications or recommendations.18If the Franzosenarzt came from outside the city there was an ever-present concern that his documents were forgeries. Joachim Camerarius, a sixteenth-century Nuremberg physician and humanist, was particularly suspicious of practitioners who qualified in foreign countries because he believed they frequently lied about their education.30 Some records of the examinations have survived in the municipal records. In 1518, the council ordered that a ‘frembd’ (‘foreign’) Franzosenarzt from Lindau was to be examined.18 Further examinations of Franzosenärzte were recorded in 1531 (one non-native), 1536 (for two, likely natives), and 1537 (one non-native).18 These examinations were most probably carried out by physicians and or surgeons, perhaps accompanied by a council official. This type of examination and regulation was further codified in 1592, when the council ordered that ‘specialists’, such as bone setters and dentists, were required to demonstrate their skills before the newly established Collegium medicum. This was an institutional body dominated by the physicians that operated under the mandate of the Rat to regulate the practice of medicine in Nuremberg.14 Therefore, although they were highly valued, the Franzosenärzte, like other empirics and specialists, were not simply given free reign, and their position was subject to the more powerful physicians, who had been cultivating links with the inner council and sought to position themselves as they city’s supreme medical authorities throughout the 1500s.

Like the physicians and surgeons, the approved Franzosenärzte were required to swear an oath to serve the city, work for its wellbeing, and obey the council. The record of duties maintained that the Franzosenarzt was not to cause harm to his patients, many of whom would come from the city’s native poor.26 They were to visit the poxed in the municipal government’s care every other day, and the council was emphatic that they should carry out their treatments with great diligence. The council also instructed that the Franzosenärzte should not refuse treatment to anyone who sought their cures outside of the municipal pox institutions, as long as they offered payment. Evidently, despite their absence from the existing historiography, the Franzosenärzte were not marginal figures, but an essential part of Nuremberg’s healthcare system during the first half of the sixteenth century.

Once approved by the council, a Franzosenarzt could aspire to a relatively profitable career. In February 1540, the council authorised a payment of 15 Gulden to a Franzosenarzt for his care of the sick (unfortunately, the record does not state the duration of the treatment but it is unlikely that the period surpassed one year).18 To put this in perspective, sixteenth-century Nuremberg’s best-paid official physician earned 200 Gulden per annum in the 1560s, whilst the lowest paid, hired in 1548, received 20 Gulden per year from the council.14In Zwickau, the Franzosenarzt also received substantial remuneration for his services; in 1522 he was to be given a free place to live and a supply of firewood. In 1573, that city decided to pay 12 Groschen weekly to the Franzosenarzt treating the sick in a municipal hospital (Lazaret). Uhlig calculated that this would be enough to purchase 10.9 kilograms of the best beef.11Furthermore, in Nuremberg, the Franzosenärzte could also take on private patients, who did not come through the municipal healthcare system, opening up further sources of profit.

However, even Franzosenärzte who received permission to practice in Nuremberg remained under close surveillance. Those who failed to meet the council’s standards could be banned from practising in the city at any time.18 For instance, in December 1539, Michael Seela petitioned the council for permission to continue practising and receiving a livelihood from the city. However, the Rat was not convinced of his competence and ordered that he should treat his existing patients for only a further 14 days. He was also forbidden from taking on new patients.18 On 13 November 1539, a Franzosenarzt was ordered to perform his cure but, after 14 days, the patient was to be inspected by the doctor and the barber-surgeon.18 This may have been due to doubts about the identity of the patient’s illness or the efficacy of the Franzosenarzt’s cure. Later that month, on 28 November, the Ratsverlässe recorded that persons who were healed by the Franzosenarzt and had become reinfected were to be visited, presumably by council officials or designated medical practitioners, and questioned about their illness.18The council probably sought to discover whether they had contracted the disease again through an incorrect regimen or whether there was a possibility that the Franzosenarzt’s treatment had failed. The tight regulation of the Franzosenärzte was typical of Nuremberg, where the council had banned guilds after the artisan revolution of 1348–1349 and closely controlled all trades as it strove to develop and maintain far-reaching control. The constant surveillance of their practice in the sixteenth century is also a further indicator of the council’s fear of quack practitioners and their growing regulation of the medical marketplace. The physicians’ and surgeons’ roles as examiners and inspectors (notably, there is no evidence to suggest that a Franzosenarzt could be examined by another trusted Franzosenarzt) also demonstrates that although the council valued the Franzosenärzte, they never achieved the same level of confidence.

The disappearance of the Franzosenärzte

The Franzosenärzte disappeared from Nuremberg’s Ratsverlässe after 1557;18 the reason behind this disappearance is not clear from the council records. However, a consideration of the broader context provides some suggestions. The Second Margrave War (1552–1555) cost Nuremberg four and a half million Gulden and ‘ruined its finances’, leaving its economy weak.31Among the damages suffered by the city was the burning of its Franzosenhaus (French pox hospital). Guarding its weakened economy and faced with the cost of rebuilding the Franzosenhaus, the council became increasingly cautious about its expenditure on victims of the disease and sought to limit it to only the most essential costs.

Diminishing demand

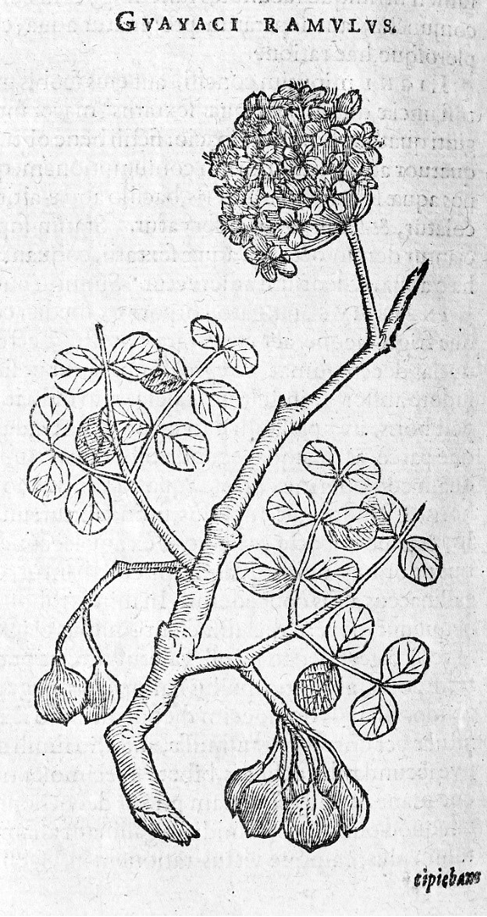

Furthermore, physicians and surgeons in Nuremberg and beyond were increasingly confident of their ability to cure the French pox. Many of these treatments were based on the guaiacum wood (Figure 3) brought from the Americas, along with applications of sweating and mercury therapies, when deemed necessary. During the 1550s, Franz Renner, a Nuremberg Wundarzt (surgeon) who worked for the council in the city’s pox institutions, published his Handtbüchlein (‘Manual’), which expounds the virtues of the guaiacum therapy.19 The text portrays a surgeon who was wholly confident of his understanding and treatment of the French pox. Moreover, this confidence was endorsed by the council who permitted Renner to dedicate the work to them.19,32Elsewhere, in Augsburg in 1522, a group of physicians persuaded the council that guaiacum therapy was a ‘miracle cure’ for the pox.2 With the standardisation of treatment came a restructuring of medical practitioners’ positions in Augsburg’s Blatterhaus. From then on, the institution would only employ two healers, a physician and a barber-surgeon.2Using practitioners already employed by the city who could treat numerous ailments and injuries would have been more cost effective than paying for practitioners who specialised in a single disease. During the late fifteenth century, Nuremberg had between two and five official physicians at one time. By 1525, the number had risen to seven and later in the century reached nine.14 During the sixteenth-century Nuremberg attracted some of the best physicians in the Germanic lands; thus it possessed a strong base of reputable and multitalented practitioners and the need for the Franzosenärzte diminished.

Figure 3 Charles de l’Ecuse, Indian Guaiacum – a branch illustrated. Source: Wellcome Collection; https://wellcomecollection.org/works/ue4uyqee. Licence: CC BY 4.0.

The profession of Franzosenarzt emerged in response to the demand for effective practitioners created by the French pox and the uncertainties of established medical authorities about how to treat this sickness. Between circa 1497 and 1557 in the city of Nuremberg, the Franzosenärzte were highly valued by the city council. They rapidly became an integral part of the municipal healthcare system and could aspire to profitable careers. This represented a threat to the physicians’ ambitions to cement their position at the apex of Nuremberg’s medical hierarchy. The existence of specialised practitioners, such as the Franzosenärzte, who challenged the local healing community triggered a discussion amongst this community about their authority over the human body and their hierarchical order within the city’s community of healers. Who can treat what became a question and research has shown that at least part of this battle was fought over the treatment of unknown diseases, such as French pox. However, the council, worried that quack practitioners would do harm to their citizens, also enforced strict regulation of the Franzosenärzte, testing their abilities and closely monitoring their practice. The city’s physicians played a key role in proliferating these anxieties and examining the new empirics. Thus, the physicians’ supremacy was ultimately further enforced. The physicians’ and surgeons’ rising influence and their confidence in standardised treatments, along with Nuremberg’s financial problems, fused with the prevailing fears of medical malpractice to precipitate the disappearance of the Franzosenärzte from Nuremberg around 1557. However, the Franzosenärzte did not uniformly fade from the Germanic lands or the popular consciousness. Zwickau retained a Franzosenarzt until at least 1573,11and Knobloch was still writing about their misconduct in 1620.21 Furthermore, in the 1658 edition of his book on the treatment of the French pox, Peter Sartorius, a surgeon at Strasbourg’s pox hospital (Blatterhaus) described himself as a Franzosenarzt.33 This raises a number of questions: Why did Sartorius use this term to describe himself? How long did the role of Franzosenarzt survive across the German-speaking lands? If so, did it change over time? Undoubtedly, much research remains to be done on the Franzosenärzte and their relationships with medical and civic hierarchies across the Germanic lands.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank The Leverhulme Trust who generously funded my PhD at the University of Glasgow, from which this article has emerged.

References

1 Cohn SK. Epidemics: Hate and Compassion from the Plague of Athens to AIDS. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2018.

2 Stein C. Negotiating the French Pox in Early Modern Germany. Farnham: Routledge; 2009.

3 Arrizabalaga J, Henderson J, French R. The Great Pox: The French Disease in Renaissance Europe. London: Yale University Press; 1997.

4 Moore M, Solomon HC. Joseph Grünpeck and his Neat Treatise (1496) on the French Evil: A Translation with a Biographical Note. Br J Vener Dis 1935; 11: 1–27.

5 Quétel C. History of Syphilis. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1990.

6 Jütte R. Syphilis and Confinement: Hospitals in Early Modern Germany. In: Finzsch N, Jütte R (editors). Institutions of Confinement: Hospitals, Asylums, and Prisons in Western Europe and North America, 1500-1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. p. 97–115.

7 McGough L. Gender, Sexuality, and Syphilis in Early Modern Venice: The Disease that Came to Stay. Houndmills: Palgrave Mamillan; 2010.

8 Maximilian I. ‘Kgl. Mandat gegen gotteslästerung’, Worms, 7 August 1495. In: Angermeier H (editor). Deutsche Reichstagsakten Unter Maximilian I. Göttingen; 1981. p. 575.

9 Sudhoff K. Die ersten Maßnahmen der Stadt Nürnberg gegen die Syphilis in den Jahren 1496 und 1497. Arch Für Dermatol Syph 1913; 118: 1–30.

10 Sudhoff K. Sorge für die Syphiliskranken und Luesprophylaxe zu Nürnberg in den Jahren 1498–1505. Arch Für Dermatol Syph 1913; 118: 285–318.

11 Uhlig P. Die Franzosenkrahnkheit im Spiegel Zwickauer Ratsprotokolle. Sudhoffs Arch 1942; 35: 113–6.

12 Uhlig P. Arzt und Apotheker in Altzwickau’, Sudhoffs Archiv für Geschichte der Medizin und der Naturwissenschaften. Sudhoffs Arch 1938; 30: 301–6.

13 Uhlig P. Fahrende Ärzte. Sudhoffs Arch 1935; 28: 264–6.

14 Murphy HS. Reforming Medicine in Sixteenth Century Nuremberg. Berkeley: University of California; 2012.

15 Strauss G. Nuremberg in the Sixteenth Century: City Politics and Life Between Middle Ages and Modern Times. Indiana: Indiana University Press; 1976.

16 Fleischmann P. Rat und Patriziat in Nürnberg: Die Herrschaft der Ratsgeschlechter vom 13. bis zum 18. Jahrhundert. Vol. 1. Neustadt an der Aisch; 2008.

17 Murphy HS. Supplications and Civic Rule in Sixteenth-Century Nuremberg [Internet]. The Many-Headed Monster. 25 November 2016 [cited February 2020]. Available from: https://manyheadedmonster.wordpress.com/2016/11/25/supplications-and-civic-rule-in-sixteenth-century-nuremberg/

18 Staatsarchiv Nürnberg, Ratsverlässe. 1495.

19 Renner F. Ein new wolgegründet nützlichs und haylsams Handtbüchlein. Nuremberg; 1559.

20 Rostinio P. Newer außführlicher unnd nutzlicher Tractat Von den Frantzosen. Frankfurt am Main; 1626.

21 Knobloch T. Die lue venere, von Frantzosen kurtzer Bericht. Giessen; 1620.

22 O’Brien MC. Contagion, Morality, and Practicality: The French Pox in Frankfurt am Main and Nuremberg, 1495-1700. Glasgow: University of Glasgow; 2020.

23 Santing CG. Medizin und Humanismus: Die Einsichten des Nürnbergischen Stadtarztes Theodericus Ulsenius über Morbus Gallicus. Sudhoffs Arch 1995; 79.

24 Ulsenius T. Vniuersis littera[rum] Patronis in Epidimica[m] scabiem que passim toto orbe grassat[ur] vacitiniu[m] dicat. Nuremberg; 1496.

25 Savinetskaya I. The Politics and Poetics of Morbus Gallicus in the German Lands (1495-1520). Budapest: Central European University; 2016.

26 Stadtarchiv Nürnberg, D15 S14/15. 1500.

27 Murphy HS. A New Order of Medicine: The Rise of Physicians in Reformation Nuremberg. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press; 2019.

28 Lindemann M. Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

29 Neufassung der Medizinalordnung. [Nuremberg]; 1679.

30 Cohn SK. Cultures of Plague: Medical Thinking at the End of the Renaissance. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010.

31 Scott T. Town, Country, and Regions in Reformation Germany. Leiden: Brill; 2005.

32 Newhouse AM. Outside the Walls: Civic Belonging and Contagious Disease in Sixteenth-Century Nuremberg. University of Arizona; 2015.

33 Sartorius P. Frantzosen Artzt. Erfurt; 1658.