Introduction

Preliminary evidence has suggested that care home residents are especially vulnerable to COVID-19 exposure and morbidity, with 57% of all European COVID-19 deaths originating from care homes.1 It is reported that protective strategies and personal protective equipment (PPE) were insufficient at this time, as they were perceived challenging for health and social care professionals to access, thus leaving vulnerable patients at risk.2 As a result, care providers, both within and outside of care homes, urgently required safer and more suitable methods of providing care that were considerate of the frailty, multimorbidity and disability of care home residents2 without introducing further risks into the homes. One way of ensuring these criteria were met was the implementation of video consulting (VC).3

Initial studies reveal VC is useful in mitigating negative psychological impacts of isolation (for example, anxiety, stress, depression and loneliness),3 in that internationally, many long-stay facilities are rapidly implementing VC into routine practice. A recent study found that the convenience and flexibility of VC resulted in Australian care providers ‘ramping up’ the use of VC from staff meetings to GP appointments.4 A study prior to COVID-19 found that VC can be used to increase family contact, which reduced feelings of social isolation, thus supporting the mental health and wellbeing of residents.5 The social isolation periods used to limit the spread of coronavirus have been linked with increased rates of loneliness and depression, and therefore it is considered important to understand if there are methods to limit these negative impacts.6 Early COVID-related data demonstrate that there is potential for VC to improve quality of life and reduce loneliness during the pandemic, concluding that VC could become a permanent feature within care homes.6 Nevertheless, COVID-19-related data within care homes are limited, and it is essential that further research into the use and value of VC is conducted.7

Methods

In March 2020, when the COVID-19 emergency was announced in Wales, the NHS Wales Video Consulting (VC) Service provided by Technology Enabled Care (TEC) Cymru8 was developed to roll out ‘Attend Anywhere’ (AA) VC appointments across all Welsh NHS services. Interviews with NHS AA users identified a need to link in with care homes but reported that many were experiencing difficulties with accessing VC, such as poor or no internet connectivity, a lack of available resources/devices or limited technological literacy of staff, thus impacting on the uptake of VC.9

Funded by the Welsh Government,10 TEC Cymru is a multidisciplinary team of clinical, project, technical and research members, who are collaborating with Digital Communities Wales11 to roll out the NHS Wales VC Service with care homes to explore these difficulties further. TEC Cymru obtained service evaluation approval from research and development departments from all health boards to evaluate patients, families, carers and clinicians (care homes within the definition of NHS patients and carers).

Over an eight-week period between September and November 2020, data were collected from a total of 101 care homes across Wales. The method of data collection was a structured telephone call interview, which consisted of the interviewer(s) randomly calling telephone numbers from a master list of care homes across Wales. Upon phoning each care home, the interviewer asked to speak to the manager (or other staff member if more appropriate). After providing information about the service evaluation, the interviewer obtained consent from the respondents to take part in a series of structured questions regarding their experience of VC. A mixed-methods approach was used to analyse the data to capture quantifiable and narrative data.

Ethical approval

Full ethical committee approval and a risk review (SA/1114/20) were obtained, with additional permissions granted by all local Welsh Health Boards to undertake evaluation relating to the NHS Wales VC Service by TEC Cymru.

Results

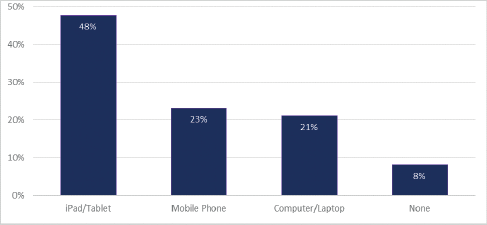

In total, 101 care homes were interviewed, of which 92% reported to be using VC. Figures 1 and 2 display the types of devices and platforms used for VC.

Figure 1 The usage of the types of devices within the care homes

Figure 2 The proportion of platform usage within care homes

Use and value of video consulting (VC)

To explore the perceptions of ‘use and value’ the responses were recorded by taking handwritten notes, which were extracted and analysed to observe any commonalities between the care homes. Out of the 101 care homes, 89% of homes reported to be ‘using’ VC for one or more reasons.

VC was used for keeping residents in touch with family members who were not permitted to visit during the COVID-19 restrictions, which as a substitute for face-to-face meeting was reported to impact positively on residents’ mental health and wellbeing.

‘Gives residents a massive lift being able to see and talk to family members, which has helped with their mental health.’

‘Amazing for mental health of residents, and for boosting morale. We now use VC much more than the telephone.’

‘Really helpful … some residents talk in riddles, but they speak fully coherent to family via VC. It’s brilliant mental stimulation.’

In addition, 67% of care homes reported to have been offered VC as a link to NHS services and local authorities. These were mainly to general practitioners (GPs), mental health teams, dieticians, speech and language therapists, physiotherapists, and social workers.

‘Handy for appointments with the psychiatrist, and reduces waiting times and the amount of people in the home.’

‘Beneficial for sending pictures e.g. with a rash to a GP and saves so much time.’

‘Very useful, especially for ward rounds.’

Many stated that they could see the use and value in having VC links with different NHS services that had not yet offered them VC, with examples including GPs, mental health, speech and language, continence, dermatology, neurology, diabetes, dentistry, optometry and dementia care.

‘We reached out to a dentist, but haven’t heard back since.’

‘We would like to use VC for extreme circumstances like for end of life or serious diagnoses … We have asked GP for this service but they never got back to us.’

The overall perception of the use and value was reported as positive by respondents (89 responses, 83%).

‘Yes, massive value. Use it with 2–3 local GP surgeries. Really valuable for clinic rounds with GPs.’

The usage was often associated with being more convenient for the residents and staff, and therefore valuable in saving time and the need to travel to face-to-face appointments.

‘Very easy to use platform. Saves time and increases access to support. Get more advice and guidance, and increases the speed of treatment such as medication reviews.’

‘Very valuable … In fact, been more beneficial than face-to-face in some instances. There are some things that would’ve been impossible if not for VC.’

VC was also reported as being used for other purposes within the care home, such as staff and professional group meetings.

‘Find it very useful for staff meetings across different homes.’

‘Good as you can involve the care home manager, healthcare clinicians, other care providers and the resident.’

However, 3% of the respondents did not consider VC to offer them much use or value, and 13% were unsure, or highlighted its use and value only in specific circumstances, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic.

‘It’s a small home, so limited use.’

‘It’s really good, but staff are unsure.’

Some of the care homes reported VC to have limitations on its use and value, while others expressed a preference for telephone calls or face-to-face consultations.

‘Yes [we see the value of VC] but many services i.e. district nurses or CPNs prefer phone calls still.’

‘They (staff and residents) do see value, but are happier to just use the telephone.’

Benefits of VC

All respondents were asked about the benefits of VC. One important aspect of VC was that it allowed a reduction in the level of visitors and health professionals entering the homes, and possibly introducing risks of COVID-19 transmission. There was an element of safety felt by many respondents, in that these risks were significantly reduced due to the implementation of VC. In addition, VC reduced the need for residents to leave the home and travel to appointments, once again limiting the risk of exposure to infection, as well as saving time that would be taken up by travel.

‘Quicker and safer … Less formal than physical appointments and reduces the need for excess people in the home.’

‘Easier to facilitate appointments and saves the nurses having to leave the home.’

‘Useful for emergency admissions when residents didn’t have time to talk to family, giving them a chance to discuss with the family and to keep their spirits high.’

VC was reported as beneficial for specific appointment types, such as those with mental health teams and GPs. For these situations, respondents praised the addition of a visual element to VC that would not have been available when using the telephone.

‘Reduces strain on the NHS. Much quicker for things like rashes, and easy for younger staff who are familiar with using the devices.’

‘A lot faster to diagnose non-fatal aliments.’

‘The visual element of VC is much more beneficial to provide clarity on what condition the resident has … very useful in the peak.’

The use of VC allowed residents to link in with their families, which was perceived as a significant personal benefit for residents, enabling regular contact during times of social isolation. Examples were reported to include speaking to families living both locally and abroad; to celebrate birthdays; meeting a new baby; and to attend a virtual funeral. The ability to do this was reported to reduce the stress and anxiety levels of the residents, specifically for those who were suffering from dementia.

‘One woman is non-verbal and is expressionless, but when she’s using the video chat with her husband, she’s happy, smiles and interacts.’

‘The residents are loving it, especially for families who live abroad.’

‘When residents celebrate their birthdays, they host a little party on VC with families, who get to see residents open gifts and cards.’

‘One resident has a great-great-grandchild born during lockdown, so got to meet the baby via VC, which really boosted morale.’

‘Even allowed a resident to attend a funeral via video.’

In addition, the ability to receive virtual healthcare was considered to have a calming impact on residents. Some reported that the residents felt more open to speak on VC compared with face-to-face, and that sessions were more private.

‘VC has benefited anxious or irritated residents with dementia, and helps calm them.’

‘Increases patient comfort when they may not feel able to say certain things face-to-face.’

It was also reported that VC services were offered at a much faster speed compared with other consultations, such as face-to-face and telephone, which ultimately lowers stress and anxiety of both staff and residents.

‘Generally, residents really enjoy it. It allows for smaller ailments to be seen quicker, and in certain instances VC is much better.’

‘Prior to lockdown, phone calls took up to six hours wait, but since VC it has reduced waiting times and increased contact capacity, which prevents the GPs coming into the home.’

Challenges of VC

Overall, 71% of 84 respondents reported some initial difficulties with using VC with their residents.

‘Non-communicative patients, so was initially difficult to use.’

‘Most can use it fine, but dementia patients only manage it with help from staff.’

‘Older residents were unsure how to use VC at first as it was completely new to some of them … starting to get to grips with it now.’

However, the majority of the care homes had positive responses in terms of resolving these issues, reporting to be fully equipped and having adequate knowledge and skills to make this process as easy as possible.

‘Technology is new to the elderly, but the home has allocated time within the nurses’ shifts to allow for VC. Nurses are able to teach them how to use it.’

‘Residents with learning disabilities require constant supervision from care staff, but it is easy to do as it’s easy to use.’

‘Some residents with hearing difficulties struggle to understand how to use it, but if the resident wants someone in the room with them, then we have someone in there to help them.’

The majority of care homes reported that their staff have the appropriate skills to use VC, and for others this was achieved after receiving sufficient training.

‘Some problems with older staff to start with, but no issues after they are shown how to use it.’

Nevertheless, a few respondents still expressed a lack of confidence in VC, often resulting in confusion and ‘struggles’, although many still seemed willing to try to use it to help their residents.

‘Some staff are older and VC is completely new to them, so it’s a learning curve.’

A total of 45% of 86 respondents reported specific issues with devices and technology. The most common was relating to Wi-Fi and internet connectivity, with mentions of slow connection causing lag, and the inability to access Wi-Fi in every part of the home.

‘Connectivity for us is the biggest concern as it loses its appeal to staff members when it keeps dropping off.’

‘The Wi-Fi is poor and doesn’t provide strong enough connection throughout the home.’

However, the remainder of homes reported no difficulties, or that they had installed (or planned to install) Wi-Fi boosters to increase access to the internet and usability of the platforms and devices.

‘Wi-Fi is a bit slow, but it is better now we have purchased “boosters”.’

‘No Wi-Fi in the home, so we use 4G. But we are making headway on Wi-Fi installation.’

Although VC was viewed positively overall, respondents still reported concerns and limitations separate to technological difficulties; for example, issues with accuracy in diagnoses.

‘Nurses are concerned about the accuracy of VC when diagnosing and reviewing more serious illness – but often due to picture quality.’

Others expressed a preference for face-to-face.

‘No substitute, as soon as face-to-face visits are allowed, we will be back to that.’

‘My concern is it needs to be reduced a bit to ensure residents have a good relationship with their GPs, but also keen to increase use when needed for convenience.’

Another concern was the need for staff to support residents using VC, thus increasing the time taken ‘off the floor’.

‘Using VC takes the staff off the floor in order for them to supervise.’

‘VC does withhold who would otherwise be available on the floor, and then we have to call in extra staff to do more hours to cover.’

Furthermore, some respondents reported a lack of VC training, or expressed concerns regarding the multitude of platforms on offer, introducing difficulty and confusion.

‘Not had any training on how to use it, so it’s confusing for us.’

‘Too many platforms, so confusing, so we need prior notice to prepare to use different ones.’

Finally, care homes were asked if they would continue to use VC post-COVID. Of 87 responses, 74% stated that they would use VC once COVID-19 had passed, although some stated that it would be used in specific circumstances or only when necessary.

Discussion

A large proportion of care homes perceived the ‘use and value’ of VC as positive. VC allowed a reduction of visitors entering the care homes, ultimately minimising the risk of COVID-19 transmission. This made attending NHS appointments more convenient by reducing both travel and appointment time for residents and staff. In addition, VC can allow residents to stay in contact with their families, improving their overall mental health and wellbeing. Issues with the ability of some residents to use VC were reported, although with staff support, this was generally successful. Concerns were reported when using VC for specific pathologies that require physical examinations in circumstances where residents have limited communication abilities. It was reported that VC added to the demand of staff time, in that additional support was needed. Regardless of the difficulties, the majority of care homes reported they would continue to use VC post-COVID-19. Thus, overall, VC seems to be accepted by many care homes in Wales.

Based on this data, care homes are clearly very responsive to using VC, with very little concern of significant difficulties with accessing devices or technology, nor did they express any unwillingness to improve their internet connectivity. Furthermore, technical literacy and the ability to put solutions in place to support residents were also evident. Rather than assuming that care homes are not able to use VC, more urgent work is needed to ensure that better communication and awareness are readily available to limit the ‘noise’ surrounding the myths, and to work more closely with care homes to ensure they are getting the best use of VC.

Nevertheless, there are still clear gaps that emerged as barriers for some care homes to use VC. For example, there is a lack of awareness regarding VC in that some respondents were unsure of the name of the ‘GP link’ (9%) they were using. Also, the majority of care homes were using a large number of different platforms at one time, potentially contributing to the confusion about VC not only for residents and staff, but also for their relationships with external VC users such as NHS clinicians and local authorities. It is therefore recommended that further awareness about the NHS Wales VC Service is needed to ensure that a better and more consistent line of communication is offered to care homes. This will be to provide support and training regarding the most appropriate and accessible platform to use, in order to take advantage of the NHS services that are available to them, which many seem to be currently unaware of. Thus, a clear messaging about the NHS Wales VC Service platform is needed, along with a single method of training and support to ensure that all NHS and local authority services are made aware of the uptake of VC within their local care homes, and to encourage a more collaborative approach between all services. Furthermore, it would also be recommended to encourage future uptake on a long-term basis to support the mental health and wellbeing of staff and residents beyond COVID-19.

At the time of data collection, there were limited logistics or protocols in place for using VC in care homes. This is likely to be due to the nature of the pandemic, and VC being adopted as an emergency. However, as Wales looks to come out of pandemic, TEC Cymru and the Welsh Government are making recommendations for the sustainable use of VC in care homes. Further research is also under way, such as observational studies. Further work is looking at linking up care homes and a wider range of services, such as healthcare, social care and third sector agencies, to get the best out of VC in the future.