Introduction

This is the first of two papers which examine a series of portraits of patients at the Royal Edinburgh Asylum (REA) which were undertaken in the 1880s by John Miles, who, as well as being a professional painter, was also an inmate of the Morningside institution. The portraits by John Miles are of interest for several reasons. They are an example of patient art, only a small portion of which has survived from nineteenth century asylums. They are also in the tradition of patient portraiture. The Edinburgh physician Sir Alexander Morison commissioned professional artists to create portraits of asylum inmates for his 1838 book, The Physiognomy of Mental Diseases.1,2 WAF Browne, Medical Superintendent of the Crichton Royal Asylum, commissioned one of his patients, William Bartholomew, to create large portraits of inmates, which Browne used in his lectures to illustrate different types of insanity.3 John Miles’s work is of interest because he was both a professional artist and a patient. His portraits also provide some insight into the patients’ world: their appearance, demeanour, posture, clothing and their surroundings in the asylum. The patients in the portraits have been identified and their case notes examined. This information complements Miles’s portraits and helps to build up a fuller picture of individual patients and their life in the Morningside asylum. The case notes also reveal the symptomatology and behaviour of the patients. They show how they were treated and viewed by asylum staff. In this paper we examine the patient portraits by John Miles, which are held at the Lothian Health Service Archive (LHSA), and a second series, held at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, which are unsigned. The identity of the artist of this second series is discussed and it is suggested that it was probably not Miles, but someone who made copies of the originals.

Life in the Royal Edinburgh Asylum

The Royal Edinburgh Asylum was opened in 1813. The death of the city’s poet laureate, Robert Fergusson in the local Bedlam in 1774 had exposed the lack of facilities in the capital for the mentally ill, and a campaign instigated by the Edinburgh doctor Andrew Duncan eventually led to the building of the asylum.4 The Royal Edinburgh Asylum was considered to be Scotland’s premier asylum, and during John Miles’s time there from 1881 to 1882, Thomas Clouston was the Superintendent, the head of the institution.5 The asylum catered for private patients who resided in the East House, and pauper patients who stayed in the West House.6 A small group of patients who paid a low rate of board stayed in the West House. The pauper patients wore institutional clothes, whilst private patients were allowed to wear their own clothes. Pauper patients were put to work in the asylum in the grounds, the workshops and the farm. In contrast, private patients could not be compelled to work. Patients were placed in the various ‘galleries’ or wards of the asylum and could be moved between galleries, depending on their level of disturbance.

During Clouston’s period of office, case note proformas were printed and set out under a series of headings: sociodemographic details; patient’s presentation; information taken from the two medical certificates which were required if the patient was compulsorily detained; and details about the patient’s mental and physical state. Finally the patient was given two diagnoses, a standard one, and one relating to David Skae’s classification. Skae, the superintendent who had preceded Clouston, developed his own classification of mental diseases based on aetiology.

The portraits

The LHSA has seven coloured loose-leaf drawings which are signed ‘JM’ and are executed in watercolour. They give the patient’s name, their diagnosis, their patient number and their case book reference. The clinical information is written in pen, most probably by a clinician, and quite possibly by Dr Thomas Clouston. Certainly the handwriting resembles his distinctive style. These drawings are held by the LHSA, whose staff identified John Miles as the artist some years ago.7

In addition, the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh has 12 portraits, six of the same patients from the original series and six further patients.8 They are also watercolours. These paintings are contained in a book titled Bruised Reeds and prefaced with a picture of a landscape with broken reeds (Figure 1). The phrase ‘bruised reeds’ comes from the Bible, Isaiah 42:3: ‘A bruised reed shall he not break’. The statement is commonly taken to advocate compassion for a person (reed) who has suffered (bruised). One can see why the metaphor has been applied to a series portraying individuals suffering from mental disturbance. The portraits are pasted into a mass-produced notebook, with a cover made of canvas-covered card. The bruised reeds image itself is the only image drawn directly into the notebook, rather than pasted in. The only mark in the book, aside from the images and descriptions of patients, is a symbol on the back cover. It may be an abstract design or a highly stylised monogram. It does not resemble the ‘JM’ signature in the LHSA series. Below this symbol is written ‘93’, which may be short for 1893, and, if so, could well be evidence that this series was done later. However, it might not be a date, and even if it is, it might not refer to when the portraits were painted, but to when they were collected.

Figure 1 Cover of Bruised Reeds. RCPE

The paintings in the Bruised Reeds series are not signed individually and are much cruder in their execution, suggesting they were done by another artist. They have an accompanying handwritten text, which gives the patient’s name and provides a brief clinical vignette. The handwriting is different from that of the series of portraits signed by Miles, though they may have also been written by a clinician. Despite the Christian allusion in the title of the collection, the tone of the texts tends to be judgemental, mocking, gossipy, and lacking in a caring, respectful attitude towards the patient. It is unclear how this series came to be created. They would appear to be copies of the original John Miles’s portraits, as they are much less detailed and they are less refined in rendering the patient’s facial features and clothing. The painted portraits also tend to be more melodramatic: the expression of the sitter is exaggerated; they strike more animated poses; and they are placed in a background of confined space. It is possible that Miles also did these portraits and perhaps they were preliminary sketches for the final portraits. However, this seems unlikely in view of the difference in artistic expertise between the two sets of portraits and the fact that the painted ones were unsigned, though one does have to take into account the fact that the case notes report that Miles was for a short period neurologically impaired to such extent that he was unable to hold a brush or see clearly. This might explain the inferior quality of the painted portraits. But, on balance, the lurid and emotional quality of the painted portraits, which contrasts with the restrained and tranquil air of the signed Miles’s portraits, adds weight to the contention that the two series were created by different artists.

It is not clear how Miles’s pictures came to be made. The portraits all contain clinical information which suggests that asylum doctors were involved in the process at some point. It is possible that they were commissioned by Dr Clouston. We do not know if Miles began drawing portraits of his fellow inmates of his own accord – he was after all a portrait painter – and doctors then became aware of this and took ownership of the material. Miles’s case notes make one mention of him painting in oils but do not say what he was painting. There is certainly no mention of him being commissioned to make portraits.

The purpose of making the portraits is also not clear. When Morison commissioned portraits of asylum inmates in the first half of the nineteenth century his aim was to illustrate the principles of ‘physiognomy’. Under this theory, the facial appearance, every expression, movement of the eyes, wrinkle of the brow, could be analysed to determine a patient’s underlying mental condition. The study of faces, therefore, enabled psychiatry to develop measurable, quantifiable tools to assist in the diagnosis of patients. By the second half of the nineteenth century the theory of physiognomy was waning as a result, in part, of its increasing association with the controversial study of phrenology. As we will see, Miles’s portraits do not seem to be trying to capture ‘types’ of mental conditions. The advent of photography in 1839 with its claims to ‘scientific’ objectivity served to undermine the value of portraits created by artists, at least in the opinion of many clinicians.

Were the portraits produced for educational purposes? They were too small, being postcard-sized, to be used in lectures, though it is possible they were photographed and projected as lantern slides. There is, however, no evidence to support this, and, in particular, no evidence that Clouston used them in his lectures. Perhaps they were intended to illustrate a textbook of mental diseases. Clouston in his The Neuroses of Development,9 incorporated several portraits of patients, but they were not done by John Miles. Perhaps the portraits were intended as a visual record of the patients at the Royal Edinburgh Asylum. Unfortunately, because of the lack of documentation, we cannot answer these questions definitively. A further suggestion is that they were featured in the asylum magazine, The Morningside Mirror, but this was not the case. An examination of the magazine draws a blank, and, in any case, the portraits with their clinical detail are not the kind of material The Mirror featured.

John Miles

Artistic career

Little is known about the artistic career of John Miles (or Myles as it is spelt in his professional life). The art historian Maureen Park researched his career, but little was found about him in the surviving records.10 There are several surviving paintings, one of which is shown here (Figure 2).11 He exhibited his paintings – portraits, landscape and genre scenes – at the Royal Scottish Academy between 1850 and 1873. The National Records of Scotland holds the collections of Edinburgh’s School of Art (now the Edinburgh College of Art). Miles is identified in these records as having been a student at this institution between 1849 and 1855.12 The records give his age as 27 years in 1849, and his occupation is originally stated as ‘glass stainer’. From 1853 onwards, his profession is simply given as ‘artist’.13

Figure 2 Edinburgh’s City Officers. Myles John. Active 1860-1873. Photo credit: Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh This may have been the picture exhibited as a ‘City Officer’ at the Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, in 1851 (no. 282)

Although the student lists provide some insight into Miles’s life, perhaps the most notable omission is his lack of a ‘recommender’. It was common for students at the School of Art to be recommended for admission and for this information to be recorded in the student lists. The gap in Miles’s entries where this information should have been recorded was particularly unusual, though there is no indication of the reason for this omission. These records do, however, indicate the ongoing interest on Miles’s part in developing his artistic credentials and, consequently, he exhibited his work almost every year between 1850 and 1873 at the Royal Scottish Academy as part of their annual open exhibition. Non-academy members such as Miles could submit pictures to this exhibition for a small fee. These artworks then underwent an onerous review process by the academy’s selection committee to determine which pictures were chosen for display. For Miles to have succeeded on so many occasions suggests both the esteem in which he was held and the perceived quality of his art.

In the asylum

John Miles was admitted to the Royal Edinburgh Asylum on 21 May 1881.14 He was then 59 years old, married and described as a ‘portrait painter’. His education was said to be good and his religion was Protestant. He lived at 6 Lothian Street and was a pauper patient from St Cuthbert’s, having been admitted via the Royal Infirmary. His disposition was said to be cheerful, intelligent and witty. For the previous two years he had been ‘very sober’, but before that he had been ‘very intemperate’. He had no previous history of insanity, nor a family history. He was regarded as suicidal. The case notes record:

Three years ago when intoxicated he had a severe fall on the back of his head. In the last year the power of his legs has been gradually failing, & of late he has felt tingling pains in his fingers, & when sitting or standing the sensation of his lower limbs has been prevented. He has recently had business anxieties. Three months ago he became manifestly changed in his behaviour, though for some time before he had been absent-minded. Became very low-spirited, thought that there was nothing but starvation before him; at times was very excited. Swallowed some paraffin in order to destroy himself. Bought charcoal to suffocate himself. Was full of groundless fears & terrors. Was very restless at night. Had a voracious appetite. Of late he has been very quiet & apathetic (p.157).

He had been ill for three months.

The first medical certificate stated:

Countenance expressive of great depression – very taciturn – says everything is wrong – that hosts of troubles are about him everywhere, everyone is a trouble and all is trouble... Nurse says he has delusions. Jumped out of bed yesterday, stating that the bed was a steamboat, and that he was a funnel, cautioned his wife not to approach the bed, as it was swarming with vermins of every description (p.157).

The second certificate stated: ‘Very melancholic… remains in bed – refuses food unless strongly pressed to do so, thinks it was dirt that made him lose his mind…’ (p.157).

On admission, he was noted to have a dejected expression and exhibit listless behaviour. He was considered to be greatly enfeebled. His memory was much impaired and ‘he never speaks, except when questioned & then his replies are very brief & slow, & he takes no interest in anything’ (p.158).

In appearance he was a ‘pale, melancholy, unwholesome old man’ (p.158). His hair was grey and scanty. His right pupil was larger than the left and irregular. Both pupils were ‘sluggish’. There was distinct impairment of power in the lower limbs, slight in the upper limbs. He dragged his legs along when he walked. His patellar (knee) reflex could not be elicited. The notes went on:

In walking & sitting he has the feeling of a wooly sensation in his soles & buttocks. The grasp of his hand is also defective, sensation being prevented so that he cannot now hold a brush properly. Sight is defective & hearing slightly so. After looking at an object for some time the image becomes blurred & indistinct. He is also subject at times to a sensation of choking in his throat (p.158).

Not being able to hold a brush properly would, of course, be a serious problem for a painter and affect his very livelihood.

Miles was catheterised because of urinary retention. His diagnosis was ‘Melancholia’, and Skae’s classification was ‘Senile Insanity’. Miles exhibited many of the classic symptoms of melancholia. He was low in spirits, suicidal, had delusions of a depressive nature, he refused food and he was generally slowed down in his physical and mental activity. He also exhibited neurological impairment, possibly the result of a head injury following his fall.

Miles was placed in the 5th Gallery. He remained despondent but showed some improvement after a week. On 30 June he was judged to be ‘considerably improved’ (p.159). On 8 December he displayed ‘considerable excitement’ and had to be removed from the 8th to the 3rd Gallery. On 28 December the case notes recorded: ‘Causes much trouble to attendants by endeavouring to break windows. States that does so in order to get back to the Sickroom’ (p.159). He was kept in a room with closed shutters. On 2 January, it was reported that a shutter had been left partially open at night and that Miles had put his left foot through the glass window, sustaining a wound to his leg. He was removed from the 3rd to the 8th Gallery.

There were no further entries until 1 October: ‘Miles has recovered. He remembers nothing of his late illness. He paints in oil and reads classical books & is well versed in ancient mythology’ (p.159). This is the only mention of Miles painting. Obviously, his physical state, particularly his grasp, must have improved to allow him to resume painting again.

On 16 October 1882 he was discharged ‘Recovered’.

We will now consider his portraits of asylum patients, and compare them with the unsigned portraits in the Bruised Reeds collection.

Richard Hailing

Richard Hailing was admitted to the REA on 12 January 1867.15 He was 17 years old, single, unemployed and resided with his parents in Henderson Row in Edinburgh. He was reported to have been insane for the past four or five years. The cause was epilepsy which he had been subject to nearly all his life. He was not suicidal but was considered dangerous. The medical certificates related that his ‘mind’ was ‘weakened & erroneous’ as a result of his fits. Hailing was unmanageable and very violent to his friends. He was unable to control his actions and was thus a danger to others. He was constantly muttering on one subject. On admission, the case notes record:

Is a stout – but pale & unhealthy looking boy – with a heavy & pasty vacant countenance. He is subject to constant involuntary twitching of the eyelids… considerably excited. Walks up & down – talks incoherent gibberish & is troublesome and very irritable… (p.230).

Hailing presented with neurological symptoms, disturbed speech and behavioural difficulties, most probably as a result of his epilepsy. He was placed in the 4th Gallery. By 20 January, he was considered to be ‘Very quiet & harmless generally’ (p.231). He had repeated fits. On 1 October 1878, the asylum doctor wrote:

A typical epileptic. Is subject to attacks of intense irritability, in which he is excited and very violent and abusive. These attacks come on in about once in every 3 or 4 weeks, and last for several days… during his quiet periods he shows a marked increase of the religious sentiment, is “sair” upon the Bible, & fond of making texts in coloured threads on cardboard. Masturbates heavily (p.304).

It was held that people with epilepsy had a ‘religiose’ personality, and Hailing seemed to conform to the stereotype. In his portrait, he is pictured holding a Bible (Figure 3). Alongside his religiosity, it was also noted that he masturbated frequently. Masturbation was often recorded, censoriously, in mid to late nineteenth century asylum patient records. This was the case in England, as the historian Alannah Tomkins has noted, in Australia and New Zealand, as Catharine Coleborne has demonstrated, and in South Africa.16 Indeed, excessive masturbation was such a frequently recorded occurrence amongst asylum patients that when it was not noted that in itself is considered worthy of the historian’s note.17

Figure 3 Richard Hailing by John Miles. Lothian Health Service Archive (LHSA)

By 1890, the case notes were recording:

No great change. Is becoming somewhat more stupid. Still works on canvas, is pious, and speaks with an explosive and loud style of conversation & generally angrily.18

He died on 20 August 1891, having had an attack of angina pectoris some weeks before.

This portrait is the only one that does not have a parallel, painted version. Hailing’s portrait is captioned ‘A Religious Epileptic’. He appears calm and well-dressed. He does not appear to be wearing pauper clothes, and, instead sports a patterned jacket. Hugh W Diamond in his photographs of the insane featured a woman with ‘Religious Melancholy’, wearing a cross.19 In the case of Diamond’s portrait, the question arises as to how much the image was manipulated: was the patient made to wear a cross? In the case of the portrait of Richard Hailing, similar questions arise, but the medical notes do confirm that he regularly read the Bible.

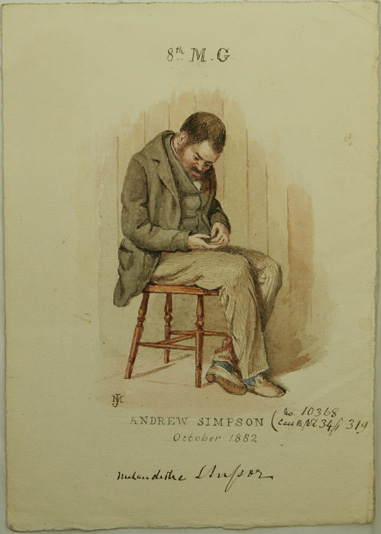

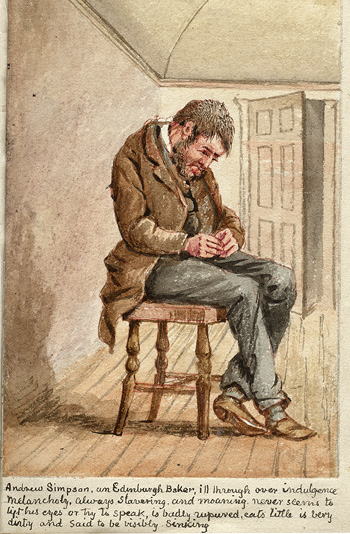

Andrew Simpson

Andrew Simpson was admitted to the REA on 5 March, 1880.20 He was a 55 year old, married baker. He lived at 53 Bristo Street, Edinburgh and was a pauper patient from St Cuthbert’s parish.

His disposition was described as ‘Always dull and desponding’ (p.319), but his habits were steady and he was very temperate. He was in a state of anxiety and grief because he could not find employment. ‘Became melancholy & depressed, & took delusions of a desperate character, such as the money of a Bakers’ Society of which he was Treasurer had been lost’ (p.319). He slept badly. He was suicidal and had tried to throw himself out a window. He had been unwell for five weeks. Medical certificate no. 1 read:

Furiously excited – keeps crying, he is done – he is done – that it must be done to-night, and constantly trying to throw himself out of the window... Wife confirms above and says it is a constant struggle to keep him from his suicidal propensities (p.319).

The second medical certificate stated the same.

On admission, he was considered to show great depression. He was very restless and unsettled. He had delusions that ‘he is lost for ever’, that ‘something dreadful is going to happen to him’ and that ‘he has injured his body beyond hope of recovery’ (p.320). He was described as a ‘thin, poorly nourished, middle-aged man, with very depressed expression’ (p.320). The diagnosis was ‘Melancholia’, and Skae’s classification was ‘Idiopathic Insanity’.

He was placed in the 5th Gallery and was under special observation because of his suicidal behaviour. He was given extra diet, but it was a struggle to get him to take sufficient food. He was described as very melancholic. By 7 May, it was reported: ‘Has sunk into a condition of melancholic stupor, & is scarcely to be roused to answer a single question, requires to be dressed, & to have his food put into his mouth’ (p.321). He continued to be depressed and a subsequent case note entry reads: ‘Chronic melancholic who sits almost in a stupor inattentive to all that is passing round him… saliva trickling from his mouth’ (p.322).

He declined physically and developed a cough. He was put to bed, but died on 7 July 1883. The cause of death was: ‘Phthisis Pulmonalis’, ‘Kidney Disease’ and ‘Brain Disease’. ‘Phthisis’ was a term for tuberculosis, a common condition during this period and to which many of the asylum population succumbed.

The first portrait captures Andrew Simpson in what is described as melancholic stupor (Figure 4). He is bent over, with his tongue protruding and seemingly oblivious of his surroundings. He is wearing the standard pauper clothing which we will see in most of the other portraits. The second, Bruised Reeds image sketches more of the background, but because the room is out of proportion with the central figure – either by design or lack of skill – the patient looks like a giant. The domed ceiling adds to the claustrophobic atmosphere of the picture. The text is judgemental and states that Simpson was ill through overindulgence, though the case notes say he was very temperate.

Figure 4 The picture on the left is by John Miles, LHSA. The picture on the right is unsigned and is part of the Bruised Reeds collection held by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. Throughout the paper we will consider the John Miles pictures first, and then the Bruised Reed ones

George Lumsden

George Lumsden was admitted to the REA on 22 July 1867.21 He was single and of no occupation. No age was given. His diagnosis was ‘Epileptic Imbecility’. The asylum doctor wrote that Lumsden: ‘Has been insane all his life’ (p.349). He was considered suicidal and dangerous. His brother reported that George had always been of weak mind and that he had been epileptic for the last eight years, being violent and excitable after his fits. The case notes recorded:

He is fond of music, & constantly plays on the violin – before an epileptic seizure he breaks everything within reach his violin included. When well he is very good natured (p.349).

He continued to have fits and became progressively enfeebled. Latterly he was unable to work in the asylum. He died in 1893 of ‘Epilepsy – 34 years. Pneumonia 3 days’.22

In the first portrait, George Lumsden is described as a ‘Musical Epileptic’ (Figure 5). He is seen playing his violin and there are no obvious signs of ‘imbecility’. He is smartly dressed. The second, Bruised Reeds, portrait is much more crudely executed. The accompanying text appears to be inaccurate, at least in terms of what the case notes tell us. He is called James rather than George and is said to have been blind since birth. This was not mentioned in the case notes and surely would have been, if true. He was described as playing the violin not particularly well and to have a bad temper, though the case notes described him as good-natured.

Figure 5 George Lumsden. On left, by John Miles, LHSA. On right, from Bruised Reeds collection, RCPE

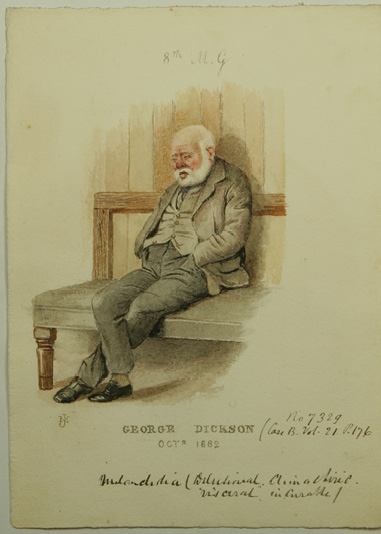

George Dickson

George Dickson was admitted to the REA on 6 May 1870.23 He was 60 years old and had been admitted previously in 1852. He was a joiner and had been widowed. He lived at 3 North Saint James Street, Edinburgh. The current attack had lasted six months. He was not epileptic, suicidal or dangerous.

Medical certificate no.1 read:

He states to me that he has committed theft, and that the Police are watching him, also that he is being poisoned by things being put into the door & window... Mrs Campbell his landlady says that she cannot control him (p.176).

No diagnosis was given, probably because he was admitted in 1870 before printed case notes were introduced and at a time when case note recording was less comprehensive. He was placed in the 4th Gallery. On 7 May, the case notes recorded: ‘On admission was quiet but listless. Says that he has got things in his shop that don’t belong to him & and that the detectives are constantly following him about (p.176).

He improved but still retained his delusions. He was removed from the 4th to the 8th Gallery. He then developed gastritis and scarlatina. His mood fluctuated, at times he was cheerful, at others depressed. He was ‘fond of doing little things in the Carpenters shop and making himself generally useful’ (p.177). Later he became confused and was in ‘a great state of anxiety about things in general’ (p. 181). His depression continued and he had to be compelled to take food. He was also given Whiskey.

On 13 July 1881, he sustained a fracture of the neck of the left femur while walking in the dormitory.24 Curiously, there are no further case note entries and we have to look to the asylum’s Register of Deaths25 to discover what happened to him. There we learn that he died on 6 October 1885 at the age of 75 years of peritonitis, pleurisy with effusion and cardiac disease (mitral incompetence).

In the first portrait, Dickson is sitting looking depressed and with his eyes practically closed. In the second Bruised Reeds, picture, his eyes are open wider and he appears scruffier (Figure 6). The accompanying text contains information not found in the case notes:

… Says he’s Dead wants to be laid out in the grounds was very successful in business but always was covetous & cruel. Is said to have thrown his wife over a window on the day after his marriage. Says he’s very poor and being constantly robbed… has to be forced to eat and gives a great deal of trouble.

Again the tone is condemnatory and lacking in compassion. One also wonders about the accuracy of the statements.

Figure 6 George Dickson. On left, by John Miles, LHSA. On right, from Bruised Reeds collection, RCPE

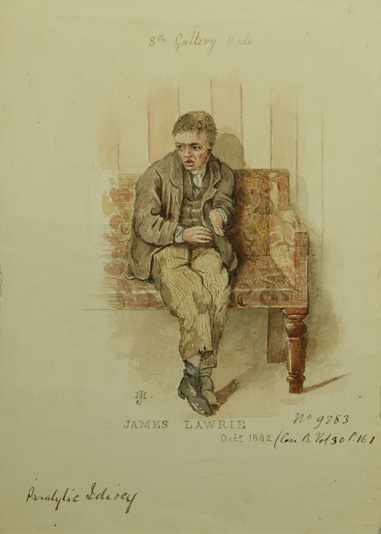

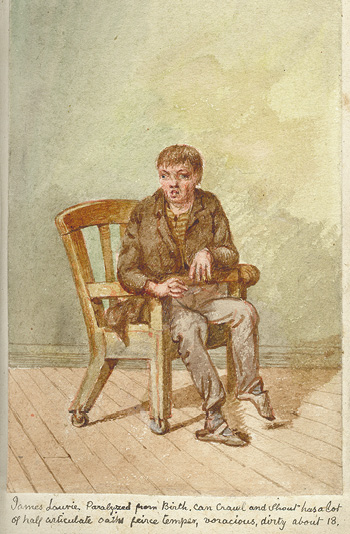

James Laurie

James Laurie was admitted to the REA on 20 January 1877.26 He was 13 years old. He had no education and was a pauper patient who was transferred from St Cuthbert’s Poorhouse. The predisposing factor was ‘Congenital’ and it was recorded that ‘Patient was his mother’s first child, she subsequently had triplets, and got the usual Queen’s Bounty’ (p.161). The Queen’s Bounty was initiated by Queen Victoria and was a donation that was given to mothers who gave birth to three or more babies at one time.27 The first medical certificate stated: ‘Inability to speak. Complete absence of intelligence’. ‘By Nurse that he is of dirty habits. The second certificate stated: ‘Idiotic – perfectly helpless’.

On admission, the asylum doctor wrote: ‘Expression of feeling limited to shrill laughter when pleased by food, musical sounds, etc. Can articulate a few words, as “baby”, etc.’ (p.162). On physical examination, James was found to be paralysed on the left side and his left foot was clubbed. He was epileptic. The diagnosis was ‘Idiocy’ and Skae’s classification was ‘Essential Paralysis of Infancy’ and ‘Insanity from Brain Disease’.

He was placed in the 8th Gallery. He had repeated fits. On 1 February, the asylum doctor wrote: ‘Is very mischievous and destructive’ (p.163). On 10 May, the doctor observed: ‘Like most idiots swears a great deal’ (p.163). On 1 July 1878, the asylum doctor wrote: ‘A noisy mischievous epileptic idiot boy… Is untidy and dirty in his habits and requires looking after’ (p.163). On 1 October 1882, the doctor made an interesting observation: ‘He calls things by onomatopoeic names e.g. when he wants to say he has heard the fiddle he says pointing in the direction whence the sound proceeded “Pum. Pum” – (the) plucking of the strings in tuning)’ (p.164).

On 7 November 1884, James died. The cause of death was ‘Brain Disease and Phthisis Pulmonalis, duration one year’ (p.176). He was 20 years old.

Both the portraits show James’s left-sided hemiplegia and his club foot (Figure 7). The text accompanying the second, Bruised Reeds, portrait reads ‘has a lot of half articulate oaths, fierce temper, voracious, dirty’. In the second portrait, James has a different pose and seems to be sitting in a chair with a restraining bar across it, keeping him confined.

Figure 7 James Laurie. On left, by John Miles, LHSA. On right, from Bruised Reeds collection, RCPE

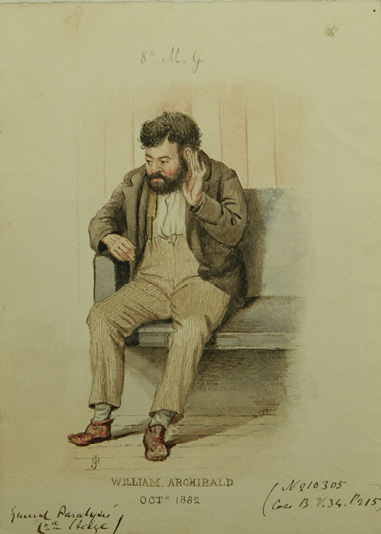

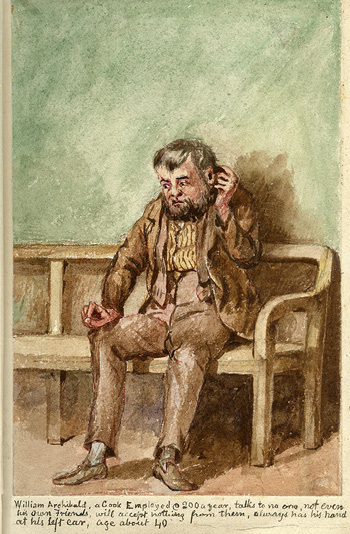

William Archibald

William Archibald was admitted to the REA on 1 January 1880.28 He was 28 years old, married and a cook. He lived at 25 East London Street, Edinburgh and was a pauper patient from St Cuthbert’s parish.

He was described as quiet and reserved, but his habits were ‘intemperate’. There was insanity in both his parents’ families. He had become ‘confused and stupid mentally, and was unable to do his work’ (p.215). He became ‘acutely maniacal this morning, very violent and destructive (p.215). He was regarded as suicidal as he had tried to throw himself out a window. He was also dangerous. He had been unwell for six months.

The first medical certificate read:

Is in a state of cerebral excitement… brain disease – and some degree of Paralysis... Has had several paroxysms of maniacal excitement – in which he had to be restrained by force, to prevent dangerous consequences to himself and others… (p.215).

The second certificate recorded the same details. On admission, he showed great excitement, was constantly restless and struggled furiously with the attendants. He had broken a window in the cab coming into the asylum. He showed great impairment of memory and was incoherent. He was described as a ‘well-nourished, dark-complexioned, strong-looking young man’ (p.216). His articulation was much impaired. The diagnosis was ‘General Paralysis’ (which we now know is the end-stage of syphilis). Skae’s classification was ‘General Paralysis’.

He was placed in the 8th Gallery in a single room with special attendants. He began to beat on the walls and the door, and had to be removed to the padded room. It was judged that his condition had already advanced to a considerable extent. However, his excitement passed off and he was able to be returned to the dormitory. He was removed to the 5th Gallery and then 4th Gallery, and became a private patient. He was more ‘enfeebled’.

On 30 June, it was recorded: ‘Patient’s idea lately has been that his neck & his legs are broken, that he has no head, & finally that he was all in pieces, which are now being fastened together’ (p.217). He deteriorated and was described as ‘very dirty and slovenly’. He persistently took off his clothes. He developed an abscess but would not permit dressings to remain on. His feet became swollen and ulcerated. He began kicking and was unsettled. He was put in a protective bed, which helped to heal the swelling and his ulcers. On 24 January 1890, he died of Bronchopneumonia (p.845). William Archibald’s case was typical of patients with General Paralysis. It was a devastating illness, in which the patient developed mental and physical symptoms and invariably died in the asylum.29

In the first portrait, Archibald looks like he is listening to voices, whereas in the second Bruised Reeds, picture, it appears he is scratching his head (Figure 8). The second portrait is much cruder. The text says he was about 40 years old, though according to the case notes he was 30.

Figure 8 William Archibald. On left, by John Miles, LHSA. On right, from Bruised Reeds collection, RCPE

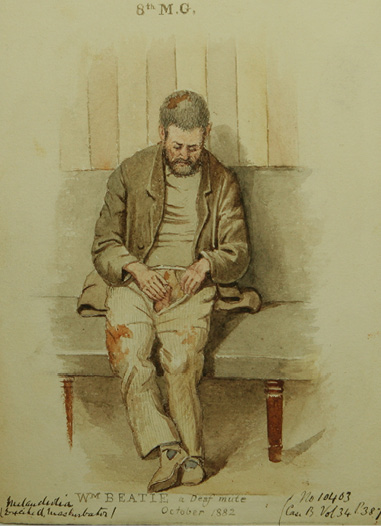

William Beattie

William Beattie was admitted to the REA on 7 April 1880.30 He was 45 years old, single, and a tailor. He had limited education. He was a pauper patient from St Cuthbert’s parish and had been transferred from Dundee Royal Asylum.

His disposition was said to be sociable, but he was also nervous and excitable. This was his first attack. His habits were steady and he had one insane relative. He had become unsettled, irritable and depressed in mind. He had also been very noisy and had tried to get out over the window. He was considered dangerous. His transfer certificate recorded: ‘He is deaf, dumb, and in a frail state of bodily health’ (p.387).

On admission he was considered to show great depression and was ‘very distressed, constantly moaning to himself in a low tremulous tone’ (p.388). Because he was deaf and dumb it was not possible to test his memory and coherence. The physician judged that Beattie ‘evidently labours under delusions of a melancholic character – points in a distressed way to his stomach, as if his trouble was all there’ (p.388). He was described as a ‘thin wretched & depressed-looking man’ (p.388). The diagnosis was ‘Melancholia’ and Skae’s diagnosis was ‘Unknown’.

Beattie was placed in the 5th Gallery. On 17 April he was so noisy in the dormitory that he had to be removed to a single room under special observation. He continued to be noisy and was kept in the padded room. Whenever anyone looked at him, he began to howl. On 25 May he moved from the 5th to the 8th Gallery. He continued to be noisy, unsettled and was ‘constantly working on his penis, & seems to indicate that he suffers pain there’ (p.389).

On 14 August, it was recorded: ‘By being kept under constant observation by a special attendant, patient has improved a little – he is more tidy in his dress, does not masturbate so openly & shamelessly…’ (p.389). He was given bromide of potassium for some weeks but developed boils, so the medication had to be stopped. He continued to masturbate ‘shamelessly’. On 1 October 1881, the asylum doctor wrote that Beattie repeatedly pointed to his stomach and seems to become passionate at not being understood. He continued that Beattie ‘masturbates openly & constantly and smears himself… with his own faeces. Drinks his own urine. Is wet & dirty. Frequently suffers from diarrhea’ (p.390). By 1 January 1886, the doctor judged that Beattie was a: ‘A most hopeless specimen of humanity’ (p.398).

Later, the asylum doctor gave an even more severe judgement:

Beattie is without doubt the most repulsive man in the Asylum. He still masturbates in an open shameless way, his penis and hands being often covered with faeces, and his mouth and face also daubed with the same. He is constantly wet and dirty. He is still dangerous to others, and will strike them or smear them with his faeces. Owing to his deafness, his dumbness, his dangerousness & his dirtyness he is most difficult to approach.31

Shortly after this entry, William Beattie died. The tone is undoubtedly judgemental but the challenges, and presumably frustrations, faced in providing care to a patient such as Beattie are clear from the descriptions of his circumstances given here.

The first portrait shows Beattie openly masturbating (Figure 9). He appears to have faeces in his hair and on his trousers. In the second Bruised Reeds, picture, Beattie strikes a different pose. He has one hand on his head, and the other is clutching his crotch. He seems wilder and more distressed. His trousers are torn. Once again the portrait seems very melodramatic. The accompanying text has a judgemental tone and describes Beattie as a ‘savage’.

Figure 9 William Beattie. On left, by John Miles, LHSA. On right, from Bruised Reeds collection, RCPE

An anti-masturbation crusade grew in fervency across Britain, the European continent and North America over the course of the nineteenth century. Its origins are commonly identified by historians in an anonymous eighteenth century text which decried the dangers of onanism to physical health.32 A shift in emphasis took place in publications on this subject over the course of the nineteenth century, moving from the danger of masturbation to physical health to its impact on mental wellbeing. Indeed, the emphasis placed on the negative effects of masturbation on mental health was promulgated by, amongst others, REA superintendent Skae and his successor Clouston.33 In works such as these, the moral and medical rationales for condemning masturbation were inexorably intertwined. Historians, including Michael Stolberg, have connected increased concern about masturbation with a broader societal heightening of moral concerns and masturbation’s association with venery and, by extension, venereal disease.34 It could also be argued, however, that there were more mundane and functional reasons why nineteenth century alienists included masturbation as a primary indicator of mental illness. In a medical specialty, such as psychiatry, where symptoms were frequently ambiguous and open to dispute, a physical indicator of mental illness that did not leave room for misinterpretation was a useful indicator.

This ends our examination of the portraits in the LHSA collection, all but one of which has been accompanied by a portrait in the Bruised Reeds series. In the next paper we will examine the remaining Bruised Reeds portraits.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Louise Williams of the Lothian Health Services Archive for the invaluable advice and information which she has provided. Without her assistance the production of this paper would not have been possible. We are also grateful to Robin Rodger of the Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture for his assistance in uncovering elusive details of John Miles’s artistic work.