Introduction

We describe a case of 43-year-old female who presented with sudden onset headache, left-sided weakness and numbness. She was found to have isolated right-side convexity cortical subarachnoid haemorrhage (cSAH) with ipsilateral severe intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis.

Case presentation

A 43-year-old female with a history of common migraines presented to the emergency department with one-day history of sudden onset headache, left arm numbness and left arm and leg weakness. The numbness and weakness resolved in 20–30 minutes. On arrival to the emergency department, she did not have any focal neurological deficit. The initial BP was 138/68 and heart rate was 79 per minute.

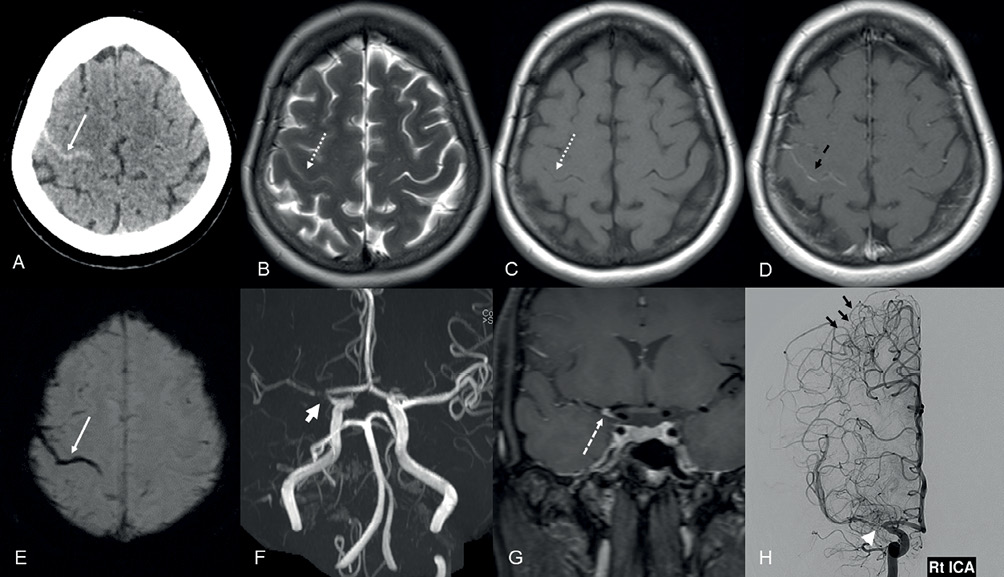

She underwent a plain computed tomography (CT) scan of the head (Figure 1A), which showed linear hyperdensity in the right central sulcus, suggesting subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH). A CT angiogram of the head and neck was performed, which showed severe stenosis/near occlusion involving the right internal carotid artery (ICA) terminus and proximal middle cerebral artery (MCA)-M1 segment. No arteriovenous malformation or aneurysm was found in neck or intracranial arteries. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and magnetic resonance venography were performed, which confirmed the right central sulcus cSAH (Figure 1B, C, E) and severe stenosis in the right ICA terminus and proximal MCA-M1 segment (Figure 1F). There was associated minimal pial enhancement in the central sulcus noted (Figure 1D). Considering the non-traumatic cSAH at a young age, extensive blood tests and interval follow-up vascular imaging were suggested to exclude diagnosis of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS).

Figure 1 (A) Axial CT section of the head showing subarachnoid haemorrhage in the right central sulcus (white arrow). (B, C) Axial T2W and T1W section of the head revealing T2W hypointense (dashed white arrow, B) and T1W isointense (dashed white arrow, C) acute subarachnoid haemorrhage in the right centrum semiovale. (D) Axial T1W post-contrast section of the head demonstrating pial enhancement (dashed black arrow) in the right central sulcus. (E) Axial SWI image demonstrating linear blooming susceptibility artefact in the central sulcus (white arrow). (F) 3-Dimensional time-of-flight MRA reconstruction of the head revealing severe stenosis in the right carotid terminus and proximal MCA-M1 segment (thick arrow). (G) Coronal post-contrast vessel wall imaging section of the head showing eccentric vessel wall enhancement in the stenotic artery (dashed white arrow). (H) Conventional right ICA angiogram anteroposterior view revealing severe stenosis in the right carotid terminus and proximal MCA-M1 segment (white arrowhead) with multiple right MCA–ACA pial-pial collaterals (short black arrows).

Blood tests including full blood count, liver function tests and electrolytes were normal. Autoimmune screen, Lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies and vasculitis screen were negative. Cholesterol was 5.68 mmol/L (<5.2), triglyceride was 3.4 mmol/L (<1.7) and low-density lipoprotein was 2.76 mmol/L (<3.36).

She was followed up four weeks later in the stroke clinic with a repeat CT/CT angiogram of the head and neck, which demonstrated persistent severe stenosis of the right ICA terminus and proximal MCA-M1 segment with complete resolution of the SAH. A conventional angiogram (digital subtraction angiography, DSA) and MRI vessel wall imaging were organised for further work up. DSA confirmed severe stenosis of right ICA terminus and proximal MCA-M1 segment, with slow antegrade flow in the distal MCA branches. There were multiple tiny pial–pial collaterals noted in the right anterior cerebral artery (ACA)–MCA watershed zone (Figure 1H). The MRI vessel wall imaging showed short segment eccentric vessel wall enhancement in the stenotic artery, suggesting underlying atherosclerotic disease (Figure 1G).

She was prescribed Aspirin 100 mg and Atorvastatin 40 mg once daily. She was followed up at six weeks and six months in our secondary prevention clinic and remained asymptomatic.

Discussion

Non-traumatic cSAH is a rare type of cerebrovascular disease different from aneurysmal SAH. Although the true incidence is unknown, an estimated incidence of cSAH from case series is 7.5–19% of all SAH.1 cSAH is associated with vascular and non-vascular causes. Vascular causes include RCVS, cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), dural and cortical cerebral venous thrombosis, vascular malformations (dural arteriovenous fistulas, pial arteriovenous malformations and cavernomas), vasculitides, mycotic aneurysms, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome and Moyamoya disease or syndrome. Non-vascular causes include primary or secondary brain neoplasms, brain abscesses and coagulopathy.2–10

Among multiple aetiologies for cSAH, RCVS is found more frequently in patients below 60 years of age, while in those over 60 years, CAA is more prevalent.11,12 A case series by Geraldes et al. reported 5 out of 15 patients with cSAH showed significant ipsilateral ICA atherosclerotic disease, two patients had RCVS and four patients had possible/probable CAA.9 In another study of 14 patients, ICA system atheromatous disease was the most common cause of cSAH, affecting 50% of the patients, with the majority having severe or occluded intracranial vessels.13

cSAH has also been observed in 0.5% of hyperacute ischaemic patients within 4.5 hours of ischaemic stroke onset and in 0.5% of cases around six days after ischaemic stroke onset. All these patients had arterial stenosis or occlusion ipsilateral to the cSAH.14 In another study, 0.14% of the patients with ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack had cSAH, and more than 60% were found to have major vessel stenosis or occlusion.15 There have been a few cases of isolated cSAH secondary to high-grade extracranial and intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis.9,12

The exact pathophysiological mechanism remains unknown in these intra or extracranial severe vascular stenosis cases and is considered similar to that of Moyamoya disease. However, the vascular imaging usually shows stenosis at the carotid bifurcations, carotid siphons or intracranial arteries without the typical ‘puff of smoke’ appearance of lenticulostriate arteries (a characteristic of Moyamoya disease).10 Therefore, the proposed mechanism seems to be haemodynamic stress associated with severe atherosclerotic stenosis, leading to rupture of the dilated fragile compensatory pial–pial collaterals in the watershed zones10,12 as evident in our patient.

In this young patient, after carefully considering multiple aetiologies of cSAH, she had detailed diagnostic work up. There was neither evidence of CVT nor RCVS. She was unlikely to have CAA due to her young age and this was proved by imaging. There was no evidence of the Moyamoya disease ‘puff of smoke’ pattern on the DSA.

Results of lupus anticoagulant, anti-cardiolipin antibodies, and vasculitis screening tests were negative with normal inflammatory markers. Her conventional angiography and vessel wall MRI clearly showed severe atherosclerotic MCA stenosis. Isolated cSAH is a rare and unique presentation of intracranial atherosclerotic disease, as evident in this case.

These patients need careful diagnostic work up, though it may be challenging due to multiple causes of cSAH. Therapeutic strategies should be tailored according to underlying aetiology. In view of atherosclerotic aetiology, the patient was started on antiplatelets and statins.

Conclusions

Isolated non-traumatic cSAH is a distinct subset of SAH associated with a wide spectrum of aetiologies. Our case report suggests that significant intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis can be presented as cSAH, although it is rare. Due to this, it requires complete investigation, including vascular and parenchymal imaging and a conventional angiogram to properly identify the underlying cause.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Hayaa Hassan, Doha College, for final proofreading.