Introduction

In 2013 a survey of Core Medical Trainees, conducted jointly by the Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board (JRCPTB) and the Royal College of Physicians of London, revealed that heavy service demands were leading to a loss of training opportunities and a wide variability in the quality of supervision.1 At the same time, there were growing concerns about potentially widespread suboptimal care in the National Health Service (NHS), powerfully documented by the failures at Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust.2 These factors were influencing some trainees against pursuing a career in the acute medical specialties. In response the three UK Royal Colleges of Physicians (London, Edinburgh and Glasgow) increased their commitment to improving the quality of Core Medical Training (CMT) via the JRCPTB and its CMT Advisory Committee (CMTAC).

The JRCPTB set up a Working Group with representatives from the JRCPTB CMTAC, Heads of the UK schools of postgraduate medicine, Health Education England, NHS Education for Scotland, the Royal Colleges of Physicians of London, Edinburgh and Glasgow and their corresponding Trainees’ Committees, to consider how best to increase the educational experience of trainees, improve the quality of the training environment and enhance wider patient safety and experience in the process.

Methods

Development methodology

A wide variety of suggestions were considered from a range of sources, including those from a 2014 UK-wide survey of trainees.3 Over 40 distinct suggestions were made. Proposals were discussed from the perspective of securing the most tangible improvements in the quality of training that could be monitored, without adversely impacting service delivery.

Another major aim of the criteria was to ensure the CMT curriculum was systematically covered by the training programme, whilst helping to build trainee confidence in performing the Medical, or General Internal Medicine (GIM), Registrar role, which was highlighted as a particular concern in the 2013 trainee survey.

The possibility of a CMT Charter was rejected in favour of a more systematic approach of monitoring a set of ‘quality indicators’ through the General Medical Council’s (GMC’s) National Training Survey (NTS), starting in 2015. Close collaborative working with the GMC was established and the phrase ‘quality criteria’ was used to make a clear distinction between these voluntary indicators and the minimum standards for postgraduate medical education and training4 enforced by the GMC. The criteria were also checked to ensure they were complementary to other relevant national guidance, for example, the Gold Guide requirements for specialty training programmes5 and the British Medical Association’s Code of Practice for employment purposes.6

The final set of agreed criteria became ‘core’ criteria (n = 14). These were perceived to contribute the most to the intended outcomes. Other commendable suggestions were deemed ‘best practice’ (n = 7). All criteria were grouped into four domains:

- A – Structure of the programme.

- B – Delivery and flexibility of the programme.

- C – Supervision and other ongoing support available to trainees.

- D – Communication with trainees.

It was agreed that the quality criteria would be integrated into UK CMT programmes from August 2015 onwards, with all criteria to be met by the end of the 2-year programme and also applied during training extensions. Implementation was led by the Heads of the UK postgraduate schools of medicine with support from CMT programme directors and College tutors (or equivalents) at a local education provider level.

Survey methodology

Following further discussions with the GMC survey team, all ‘core’ quality criteria were to be reflected in the 2015 GMC NTS, except for one (C4) on the grounds that the question had already been asked within the ‘generic’ NTS questions. In subsequent years (2016 and 2017) this question was included by universal agreement but two others were removed (B4.2, C3) on the grounds they did not add sufficient value when question numbers were limited. Some minor wording alterations were also made for clarification but did not significantly impact question content or meaning.

An online survey was sent to all CMT programme directors and College tutors (or their equivalents) via the Heads of the UK postgraduate schools of medicine in August 2015 and repeated in August 2016. In each instance the survey was open for 1 month and two reminders were sent during that period. The purpose of the survey was to receive feedback on the implementation of each of the criteria, including any practical difficulties. For brevity, this survey will be referred to from now on as the ‘trainer survey’.

Promotion of the initiative

The new criteria were formally launched in January 2015 and promoted widely to trainees and training providers using a combination of traditional (e.g. newsletters) and digital marketing techniques. This included a dedicated CMT quality criteria page on the JRCPTB website7 with a link to a PDF of the A4 background briefing document and short video extracts of the formal launch (posted on YouTube).8 In addition, all UK postgraduate schools of medicine were provided with hard copy materials and digital slides to promote the quality criteria locally; feature articles were placed in trainee and trainer e-newsletters; the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh promoted the criteria via a blog and at their monthly Evening Medical Updates; PDF copies of the documents were emailed to all UK CMT and Foundation trainees; and, an alert was set up on the ePortfolio.

Results

GMC NTS

The 2015 NTS provided ‘baseline’ data, as the survey was conducted (March–April 2015) prior to the formal implementation date (August 2015). Feedback from training programme directors was used to clarify some questions in subsequent NTSs, which led to some refinements to question response categories (A1, B2, B3, B5, D2). In two cases, baseline percentage responses were likely affected as a result (A1, D2). The criteria themselves did not change post launch (January 2015).

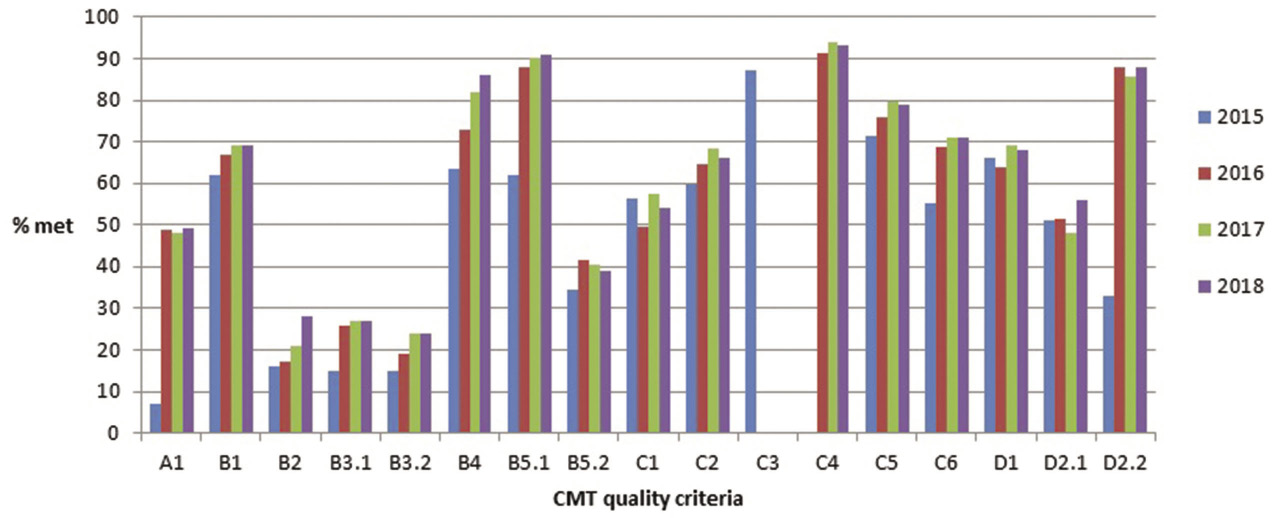

According to JRCPTB Annual Review of Competence in Progression (ARCP) records, the NTS response rates of Core Medical Trainees were 99% (2015), 96% (2016) and 91% (2017). The percentage of trainees agreeing that each individual criterion had been met in their training programme (cohorts 2015–18) is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Percentage of trainees agreeing that each individual criterion had been met in their training programme (cohorts 2015–18). CMT: Core Medical Training

Trainer survey

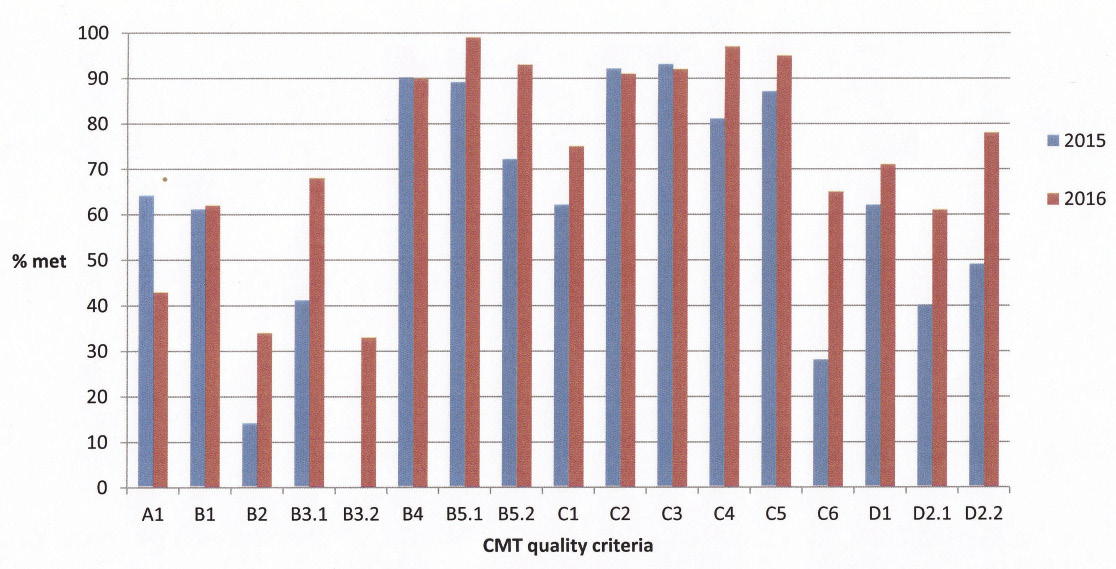

In 2015, 97 respondents filled in the survey out of a potential 255 listed as a CMT programme directors, College tutor, or both, in 2015 JRCPTB records, giving a response rate of 38%. This ratio increased (112 out of 243) in 2016 to a response rate of 46%. The percentage of trainers agreeing that each individual criterion had been met in their training programme (cohorts 2015–16) is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Percentage of trainers agreeing that each individual criterion had been met in their training programme (cohorts 2015–16). CMT: Core Medical Training

Respondents were asked to state whether they believed each of the quality criteria were being met in their area. A free-text response was provided per criterion for additional feedback. Comments were categorised as either ‘general concepts’ or ‘practicalities’ but were also used to help clarify NTS questions.

Box 1 lists the full descriptors for each criterion. Details of percentage responses, questions and question amendments are available as online supplementary material.

Box 1 Core Medical Training (CMT) ‘core’ quality criteria descriptors

A1) Trainees to spend a minimum of two-thirds of placements (usually 16 months) contributing to the acute medical take, including the acute medical unit. B1) Shift patterns to be structured to ensure trainee attendance at relevant post-take ward rounds and handovers. B2) Trainees to undertake a minimum of 40 outpatient clinics. B3) Bleep-free cover arrangements to allow trainee attendance at outpatient clinics and other learning events, e.g. PACES training as protected learning time. B4) Skills laboratory and/or simulation training for all mandatory procedural skills to be provided at least once a year to supplement clinical training. B5) A minimum of 1 hour of curriculum-relevant teaching to be provided per week on average, including a regular programme of direct observation of clinical skills around the PACES diet. C1) Trainees to be appropriately represented on and engaged with local professional and education committees, e.g. trust education committee. C2) An introduction to the system of review and assessment at a departmental level (to include ePortfolio use) to be provided within 1 month of starting the programme. C3) A named college tutor, or equivalent lead, to be appointed in all trusts to oversee CMT training. C4) Each trainee to have a single, named educational supervisor for a minimum of 12 months, who has been selected, trained and assessed as per national guidance. The supervisor’s duties and training time will be specified in their job plan according to national guidance. C5) Formal interim reviews, also known as ‘a pre-annual review of competence progression (ARCP) appraisal’, involving a training programme director (or equivalent) to be provided to all CMT trainees pre-ARCP and the outcome to be recorded in the ePortfolio. C6) The educational supervisor and trainee to discuss and agree a plan for MRCP(UK) training, to include ‘before and after’ meetings for each part of the examination. Trainees requiring more support should receive enhanced training and/or supervision. D1) Information on expected CMT rotations to be published at the time of job offers. D2) On-call rotas to normally be published at least 6 weeks in advance and to cover 4 months in length. |

Individual quality criteria

Results for individual quality criteria, in the context of free-text comments from the trainer survey, are provided below.

A1: Minimum of two-thirds of placements spent on the acute take

The large increase in percentage trainee agreement from 7% (2015) to 49% (2016) is likely to be due to clarification of question response categories in 2016. Results from 2016–18 were consistent (49%, 2016; 48%, 2017; 49%, 2018).

There was a fall in trainers who believed this criterion was being met, from 64% (2015) to 43% (2016). Trainers were concerned about language (such as the ‘acute take’) not being sufficiently clear and that trainees did not always recognise on-call duties as contributing to the medical take. There was a strong belief that most of the curriculum competencies and confidence needed to become a GIM Registrar could only be obtained whilst on-call.

B1: Shift patterns enable attendance at post-take ward rounds and handovers

There was a gradual increase in trainees attending post-take ward rounds and handovers with time (62%, 2015; 67%, 2016; 69%, 2017; 69%, 2018).

A similar gradual increase was reported by trainers (61%, 2015; 62%, 2016). Perceived problems included limited time being available for handover after night shifts but, if they occurred, the potential learning opportunities were considerable.

B2: Minimum of 40 outpatient clinics

There was an increase in trainees attending outpatient clinics with time (16%, 2015; 17%, 2016; 21%, 2017; 28%, 2018).

Trainers reported a larger increase, from 14% (2015) to 34% (2016). There were concerns about the practicalities of including more clinics and what the definition of a clinic entailed. For example, whether a trainee was merely observing or actually running a clinic, with the latter deemed educationally superior. However, despite the concerns raised, trainee attendance improved with time.

B3: Bleep-free learning events

There was an increase in ‘bleep-free’ attendance at learning events from 15% (2015) for both PACES (26%, 2016; 27%, 2017; 27%, 2018) and outpatient clinics (19%, 2016; 24%, 2017; 24%, 2018).

There was an increase in trainer agreement from 41% (2015) to 68% for bleep-free PACES teaching but a decrease for bleep-free outpatient clinics (33%) in 2016, although the latter may be due to the 2015 question having both categories combined. Some trainers felt that clinics, as per senior doctors, should not be bleep free.

B4: Simulation training

There was a sequential increase in simulation training attendance with time (63%, 2015; 73%, 2016; 82%, 2017; 86%, 2018).

Trainers consistently reported attendance at 90% and stated this training should be mandatory.

B5: 1 hour of curriculum-relevant teaching per week

There was a sequential increase in trainees reporting receiving at least 1 hour of curriculum-relevant training per week (62%, 2015; 88%, 2016; 90%, 2017; 91%, 2018). However, after an initial rise there was a slight fall in trainees reporting regular teaching pre-PACES examination (35%, 2015; 42%, 2016; 40%, 2017; 39%, 2018).

Trainers reported higher levels of both curriculum-relevant (89%, 2015; 99%, 2016) and pre-PACES teaching (72%, 2015; 93%, 2016). There was a sense that teaching was becoming increasingly geared towards trainees expressed needs, partly due to low turnouts.

C1: Representation on local committees

Trainee representation on professional committees fluctuated but remained roughly the same overall (56%, 2015; 50%, 2016; 57%, 2017; 54%, 2018).

Trainers reported higher levels of representation than trainees (62%, 2015; 75%, 2016) and some believed that greater engagement was possible.

C2: Inductions

There was a modest overall rise in trainee induction attendance, albeit falling in 2018 (60%, 2015; 64%, 2016; 69%, 2017; 66%, 2018).

Trainers reported higher levels of attendance at inductions (92%, 2015; 91%, 2016) but felt a clearer distinction was needed between regional and local events.

C3: Presence of College tutor or equivalent lead

The presence of a named College tutor, or equivalent lead, in hospitals was slightly less recognised by trainees (87%, 2015) than trainers (93%, 2015; 92%, 2016), although subsequent data were not collected.

C4: Educational Supervisor

Both trainees (91%, 2016; 94%, 2017; 93%, 2018) and trainers (81%, 2015; 97%, 2016) reported high levels of provision of Educational Supervisors for a 12-month period, although some training programmes provided supervision in 6-month blocks in 2015. Any initial reluctance to change systems appears to have been overcome prior to the 2016 survey.

C5: Formal interim reviews (or pre-ARCP appraisals)

Trainees were less likely to report having formal interim reviews (71%, 2015; 76%, 2016; 80%, 2017; 79%, 2018) than did trainers (87%, 2015; 95%, 2016), although this gradually increased with time.

C6: Plans to take MRCP(UK)

There was an increase in the number of trainees devising a plan to undertake the MRCP(UK) examination with their Educational Supervisors (55%, 2015; 69%, 2016; 71%, 2017; 71%, 2018). This is the only criterion where trainers’ agreement was lower than trainees (28%, 2015; 65%, 2016); however, the consistent rise in trainees’ responses suggest the experience is becoming more common.

D1: Information on CMT rotations

Trainees report similar levels of information offered on rotations by the time of job offers each year (66%, 2015; 64%, 2016; 69%, 2017; 68%, 2018). Trainers largely concurred with this (62%, 2015; 71%, 2016).

D2: Publication of on-call rotas

Notice given for on-call rotas fluctuated but remained broadly similar (51%, 2015; 52%, 2016; 48%, 2017; 56%, 2018). The marked increase in the number of months covered by the rotas from 32% (2015) to 88% (2016) is likely due to a clarification in survey response categories. After that results remained consistent (88%, 2016; 86%, 2017; 88%, 2018) with time.

Trainers reported an increase in both notice given (40%, 2015; 61%, 2016) and number of months covered (49%, 2015; 78%, 2016), but these figures did not readily concur with trainee experiences. A number of trainers referred to the rota disruption resulting from 2016 industrial action.

Discussion

The main driver behind the quality criteria was to improve the educational experience of CMT, with greater attention being paid to developing the skills and confidence to undertake the GIM Registrar role. The results clearly demonstrate trainee-reported improvements in training since the quality criteria were applied to all CMT programmes in 2015. These improvements most likely reflect the engagement of local trainers, possibly incentivised by peer comparison. Overall, those in charge of training programmes were more likely to agree that a particular criteria was being met than trainees; however, the much larger trainee cohort and higher response rate (averaging 95% compared to an average of 42% for programme overseers) prevents more meaningful data comparisons. The survey findings, especially the free-text comments, revealed the attention to detail that many training programme overseers adopt to improve the quality of CMT.

Where a full set of trainee results (2015–18) is available, improvements from baseline were observed in at least eight out of 13 quality criteria measured, namely: B1, B2, B3, B4, B5, C2, C5 and C6. Improvements for criteria where the 2015 baseline was likely affected by the survey category responses (A1, D2) were disregarded. It was noted that implementation of many criteria stabilised from 2017–18 with a small ‘drop-off’ effect, possibly due to a diversion of priorities towards the implementation of the new Internal Medicine (IM) curriculum (start date August 2019).9

The findings demonstrate that centrally coordinated efforts to improve the quality of CMT by focusing on specific local measures can be effective, despite no additional resources being available for implementation. The improvements reported by trainees were achieved through the coordinated efforts of the central promotion and drive for change arising from the three UK Colleges of Physicians together with a network of key stakeholders, including Heads of UK postgraduate schools of medicine, CMT programme directors, supervisors, College tutors and their equivalents responsible for implementing the desired changes at a local level.

Not all quality criteria were equally easy to implement, with some requiring cultural changes (for example, inductions and bleep-free attendance at learning events), individual behavioural changes (such as planning for examinations with supervisors) or practical changes (for example, simulation training and information on rotations). A range of approaches, including future planning, liaison with personnel throughout the training system, local promotion efforts and trainee engagement, were required. Details of how this was achieved in practice are being highlighted and promoted by NHS Employers in a bid to encourage all trusts to follow suit (email communication from K Wilson, 23 January 2019).

A principal objective of the quality criteria was to impart a sense of collective purpose and achievement to quality improvement at a programme level, for example, by also involving College tutors or their equivalents in implementation. To this end, it has largely attained its original goals, albeit that attention and resources need to be continually focused on CMT to secure further improvements, especially whilst IM curriculum arrangements are being made and for as long as the programme continues.

It is often assumed that improvements in training will lead to improvements in the quality of care, for example, the purpose of the Shape of Training review10 was ‘to ensure that doctors receive high-quality education and training that supports high-quality patient care and outcomes’. In practice there is some evidence that higher quality training results in better patient outcomes;11 however, two systematic reviews suggest the evidence linking training quality to better patient care and outcomes in the longer-term is weak,12,13 although short-term improvements in patient satisfaction are recognised.14 Adequate faculty and individual support have been highlighted as important factors in maintaining the quality of patient care during training.13

An indirect effect on improving patient care and experience was expected with the implementation of the quality criteria, but could not be demonstrated by the chosen methodology. Given the wider evidence available, however, it is likely that the additional protected time for learning, greater training opportunities and faculty support specified by the quality criteria would result in similar short-term improvements. Therefore, the expectation is that increased implementation of the quality criteria would contribute indirectly to improved patient care as well as trainee experience.

The CMT quality criteria will continue to apply until the programme is fully replaced by the IM curriculum in August 2020. Owing to the positive feedback and evidence15 received early in the implementation process, some individual quality criteria, for example those stipulating simulation training and outpatient clinic attendance, have been incorporated in an enhanced form directly into the IM curriculum. The remaining criteria will be expanded (in conjunction with the 2018 GIM and Acute Internal Medicine Registrar quality criteria)16 to form an appropriate full set of IM quality criteria for implementation in August 2020. It is expected that most existing quality criteria will continue (perhaps in an adjusted format) as apart from the inclusion of critical care attachments, the learning environment will be broadly similar to present. In addition, the momentum gained from the promotion of the CMT quality criteria, and the ensuing local and national discussion of NTS results, needs to be maintained for the benefit of IM trainees. To this end, the JRCPTB has entered into a formal partnership with NHS Employers and other key stakeholders to oversee the development of IM quality criteria and produce additional resources to support the implementation of existing quality criteria. Further analysis of the impact of quality criteria, using GMC NTS data, will continue to inform future quality improvement initiatives.

Conclusion

This paper summarises the origins and process of creating the CMT quality criteria, developed following a wide consultation process with a particular focus on the views and priorities of CMT trainees and training programme overseers. It also highlights their impact, namely, consistent trainee-reported improvements in a number of specific areas since their introduction.

There were clear improvements in at least eight out of 13 measured ‘core’ criteria from 2015–18: attending post-take ward rounds and handovers; outpatient clinics; learning events bleep free; simulation training; curriculum-relevant and PACES teaching and inductions; having pre-ARCP appraisals; and, agreeing training plans before attempting MRCP(UK).

The criteria have been applied UK-wide since August 2015 and have demonstrated their value as a means to further raise the educational value and quality of CMT without the input of significant additional resources. Where implemented, they can help improve trainee workload-to-learning balance, provide enhanced educational support and, together with critical learning opportunities, help better prepare trainees for the GIM Registrar role. With this purpose in mind, some individual criteria have been incorporated into the IM curriculum (effective from August 2019) whilst others will be integrated into a new set of IM quality criteria designed to enhance the quality of training throughout the programme (effective from August 2020).

Acknowledgements

We should like to acknowledge the numerous contributors who helped shape the quality criteria from inception to publication, in particular: Professor Bill Burr (previous JRCPTB Medical Director), Dr Michael Jones (Medical Director for Training and Development, Federation of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom), Warren Lynch (JRCPTB Quality Management), JRCPTB CMT Advisory Committee members, Heads of the UK postgraduate schools of medicine, Royal Colleges of Physicians of London, Edinburgh and Glasgow and associated Trainees’ Committees, Health Education England, NHS Education for Scotland, Conference of Postgraduate Medical Deans (UK), Northern Ireland Medical & Dental Training Agency, Wales Deanery, and the General Medical Council for their support to include the quality criteria in the annual National Training Survey.

Online Supplementary Material

Supplementary tables are available with the online version of this paper, which can be accessed at https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/journal.

References

1 Tasker F, Newbery N, Burr B et al. Survey of core medical trainees in the United Kingdom 2013 – inconsistencies in training experience and competing with service demands. Clin Med 2014; 2: 149–56.

2 For example see: Doyle E. Senior physicians call for ‘cultural change’ in NHS, Health Service Journal online. 25 February 2013. https://www.hsj.co.uk/5055373.article (accessed 21/01/19).

3 Tasker F, Dacombe P, Goddard A et al. Improving core medical training – innovative and feasible ideas to better training. Clin Med 2014; 14: 612–7.

4 General Medical Council. Standards, guidance and curricula. 2015. http://www.gmc-uk.org/education/postgraduate/standards_and_guidance.asp (accessed 21/01/19).

5 UK Health Departments. A reference guide for postgraduate specialty training in the UK (the ‘Gold Guide’), 5th edn. 2014. Later updated to: COPMeD. A reference guide for postgraduate specialty training in the UK (the ‘Gold Guide’), 6th edn. 2017. https://www.copmed.org.uk/images/docs/publications/Gold-Guide-6th-Edition-February-2016.pdf (accessed 21/01/19).

6 British Medical Association. Code of practice: Provision of information for postgraduate medical training. London: BMA, 2010. Later updated to: British Medical Association. Code of practice: Provision of information for postgraduate medical training. London: BMA, 2017. https://www.bma.org.uk/advice/employment/contracts/juniors-contracts/accepting-jobs/code-of-practice. (accessed 21/01/19).

7 Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Quality criteria for core medical training. 2015. https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/cmtquality (accessed 21/01/19).

8 Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. CMT Quality Criteria launch Jan 2015 – Professor David Black. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZBC59-GTiKA (accessed 21/01/19).

9 Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Internal Medicine Stage 1 Curriculum. 2018. https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/internal-medicine (accessed 17/04/19).

10 Greenaway D. Securing the future of excellent patient care. 2013. https://www.shapeoftraining.co.uk/reviewsofar/1788.asp (accessed 16/04/19).

11 Asch DA, Nicholson S, Srinivas S et al. Evaluating obstetrical residency programs using patient outcomes. JAMA 2009; 302: 1277–83.

12 Simons MR, Zurynski Y, Cullis J et al. Does evidence-based medicine training improve doctors’ knowledge, practice and patient outcomes? A systematic review of the evidence. Med Teach 2019; 41: 532–8.

13 Van der Leeuw RM, Lombarts KM, Arah OA et al. A systematic review of the effects of residency training on patient outcomes. BMC Med 2012; 10: 65.

14 Oosterom N, Floren LC, ten Cate O et al. A review of interprofessional training wards: Enhancing student learning and patient outcomes. Med Teach 2019; 41: 547–54.

15 Joint Royal College of Physicians Training Board. Enhancing UK Core Medical Training through simulation-based education: an evidence-based approach. A report from the joint JRCPTB/HEE Expert Group on Simulation in Core Medical Training. 2016. https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/news/enhancing-uk-core-medical-training-through-simulation-based-education-sbe-evidence-based (accessed 17/04/19).

16 Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Quality criteria for GIM/AIM Registrars. 2018. https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/quality/quality-criteria-gimaim (accessed 21/01/19).