Definition

Malignant spinal cord compression (MSCC) is defined as the compression of the spinal cord (and/or cauda equina) as a result of malignant disease. Typically this is due to extradural tumour compressing the thecal sac (Figure 1), but in rare cases it can be due to dural metastases or intramedullary tumour. MSCC arising from spinal metastases (from haematogenous spread of cancer) is consequent upon either pathological vertebral collapse or direct tumour extension into the spinal canal resulting in compression of the thecal sac. Associated oedema exacerbates the compression and the resulting mass effect causes white matter oedema, vascular compromise and eventually infarction of the spinal cord.1

Figure 1 Sagittal T2-weighted MRI image of a patient with malignant spinal cord compression at T9 vertebral level

Epidemiology

MSCC is a relatively common complication of cancer, occurring in 5–10% of patients with malignancy, often complicating the end stages of the patient’s illness. In 23% of patients it can be the presenting manifestation of malignancy.2 It is viewed as an oncological emergency as a patient’s mobility at time of diagnosis is both a significant predictor of the ability to walk independently following treatment and is significantly associated with prognosis.2 The consequences of established MSCC can be devastating, including pain, motor and sensory loss, paraplegia and urinary/faecal incontinence.

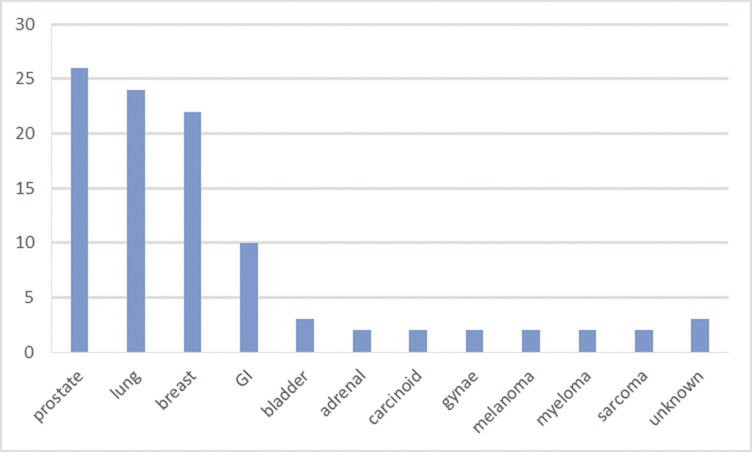

In order to identify the frequency of MSCC and the distribution of primary cancers responsible for MSCC in the local population (in advance of updating the MSCC pathway), an audit of patients presenting with MSCC to Aberdeen Royal Infirmary over a 9-month period in 2016, identified 37 patients with established MSCC with a further 21 patients defined as having ‘incipient cord compression’ (with incidental evidence of compression of the thecal sac on imaging, prior to the development of any discernible neurological compromise). All 58 patients were managed as ‘oncological emergencies’ and were identified retrospectively through the Radiotherapy Department Oncology Information System. The median age of this cohort was 65 years and the site of the compression was found to be thoracic (69%), lumbar (21%), cervical (7%) and sacral (3%) spine in decreasing frequency. All patients had undergone radiotherapy; however, only two of the patients in this audit had undergone prior surgical intervention for decompression/stabilisation, suggesting that interdisciplinary discussion of such patients might be improved in a new pathway. Figure 2 demonstrates that the most common primary tumours resulting in MSCC are prostate cancer, breast cancer and lung cancer in this cohort, accounting for approximately one-quarter of the incidence each, with diverse other tumours accounting for the remainder. The data from our audit are consistent with other series.2–4 The median survival from this condition is 2–3 months,2,4,5 the poor outlook in part a consequence of the advanced malignancy, in part due to the ensuing debility limiting systemic therapy in many patients and in part due to the complications of immobility (e.g. increased susceptibility to pulmonary complications and pressure sores).

Figure 2 Bar chart showing (in percentages) the primary tumour types responsible for the development to malignant spinal cord compression in a cohort of 58 patients in Aberdeen Royal Infirmary. GI, gastrointestinal

Clinical features

Patients with established MSCC can present with a wide variety of neurological symptoms affecting any or all of the motor, sensory and autonomic nervous systems, often in the context of radicular back pain at the level of the compression. Classically, patients will have bilateral upper motor neurone findings below the level of the compression, although unilateral findings are frequently seen. A circumferential ‘sensory level’ below which sensation is reduced or altered may be noted, and bowel or bladder dysfunction (typically urinary retention) is often present. In a smaller proportion of patients, loss of balance may be the main presentation due to loss of proprioception (resulting from compression of the posterior cord) in the absence of any motor weakness.

Key to shaping the guidelines for the management of MSCC in the UK was a prospective observational study of patients diagnosed with the condition between January 1998 and April 1999 in Aberdeen, Edinburgh and Glasgow.2 A total of 319 patients were identified, of whom 248 consented to interview and were able to provide a detailed description of their presenting symptoms. The headline findings from this study were as follows:

- At the time of diagnosis 82% of patients were unable to walk independently.

- Pain was described in 94% of patients and had been present for a median of 3 months prior to the diagnosis of MSCC being made.

- Pain had the typical distribution and nature of nerve root pain in 79% of patients (with descriptors such as ‘band-like’ thoracic pain, ‘worse on sneezing, coughing or bending’, ‘sharp’, ‘burning’, ‘worse on lying flat’).

- Weakness or difficulty walking was reported in 85% of patients and was present for a median duration of 20 days preceding diagnosis.

- Sensory changes were noted by 68% of patients, for a median of 12 days preceding diagnosis.

- Alteration in bowel or bladder function was noted in the majority of patients.

This study clearly identified that the large majority of patients with MSCC were diagnosed too late for intervention to be of major benefit, and that symptoms, in particular pain in a characteristic nerve root distribution, that could have alerted the patient and healthcare professionals to the impending development of MSCC were present in most patients for several months before neurological compromise was noted. A timeline analysis revealed that the delays from first symptom to the diagnosis being made were multifactorial, relating to delays in patients recognising the importance of symptoms and seeking advice, delays in primary care and onward referral, and delays in secondary care (in particular access to MRI and to timely intervention).

In order to improve the early diagnosis and subsequent management of patients with MSCC, in 2008 The National Institute for Clinical Excellence published ‘Metastatic spinal cord compression: diagnosis and management of patients at risk of or with metastatic spinal cord compression’, a guideline that sought to provide a framework for cancer networks to develop local pathways and services and against which those pathways could be audited.4

Some of the key recommendations are as follows:

- Ensure adequate information provision to patients at risk of MSCC.

- Development of an MSCC coordinator role as a single point of contact for patients (and their caregivers) who experience symptoms suspicious of impending MSCC or with established neurology.

- Improved access to MRI facilities.

- Consistent nursing procedures if spinal instability is suspected.

- Early commencement of definitive therapy, including access to radiotherapy services 7 days a week.

The pathway in NHS Grampian

In order to create a more consistent and streamlined approach to the management of patients with suspected and/or established MSCC, a multidisciplinary group was convened in 2016, comprising clinical oncologists, spinal surgeons, radiologists, clinical nurse specialists, ward nursing staff, physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

Information provision to patients, family and carers was a priority, to alert patients at risk of MSCC to early symptoms, empowering them to seek help prior to the development of any neurological compromise. MacMillan Cancer Support produce a leaflet (with an accompanying ‘wallet-size’ card), detailing the common early warning symptoms (an extract of which is seen in Box 1), along with details of what to do in the event of developing such symptoms.6 Local contact details for the MSCC coordinator are added to the leaflet.

Box 1 Extract of the information provided in the MacMillan Cancer Support malignant spinal cord compression leaflet6

|

- Unexplained new back or neck pain:

- The pain may be mild to start with but becomes more severe.

- It may feel like a ‘band’ around your chest or abdomen.

- The pain may spread down your leg or arm, or into your lower back and buttocks.

- Movement may make the pain worse.

- The pain may get worse when you strain – for example, if you lift something heavy, cough or sneeze.

- The pain may keep you awake at night.

- Numbness or pins and needles in a part of your body, such as your toes, fingers or over the buttocks.

- Feeling unsteady on your feet – having difficulty walking, leg weakness or your legs giving way.

- Problems passing urine:

- You may have difficulty controlling your bladder (incontinence).

- You may only pass small amounts of urine or none at all.

- You may be constipated or have problems controlling your bowels.

|

In the NHS Grampian pathway, the MacMillan leaflet is currently given to patients with known bony metastases, although in due course we may expand the MSCC information provision to other patients with malignancies that put the patient at particular risk of MSCC even in the absence of current bone involvement (e.g. renal cancer and lung cancer), with such groups being identified through planned future audit of the pathway. Whenever a leaflet is given to a patient, a standard letter is sent to the general practitioner detailing the same information that the patient has received, with a request for the information to be added to the Key Information Summary on the patient’s electronic record so that ‘out of hours’ teams are aware of the potential for MSCC.

The MSCC coordinator role was developed within existing resource by incorporating this into the remit of the clinical nurse specialists and advanced nurse practitioners through the day, and the on-call middle grade medical staff out of hours. Different regions in the UK have developed their own solutions to the development of the MSCC coordinator role, but the common theme is one of a single point of contact for patients/carers and primary care staff to discuss patients where the concern over MSCC is raised.

In Grampian, we developed a proforma for the MSCC coordinator to use when responding to such calls, ensuring that sufficient information is consistently requested and recorded regarding patient demographics, recent oncological management, prior radiotherapy or surgery, relevant comorbidity and current symptoms. The patient is then given advice about further management (often after discussion with the responsible oncology team). There are four potential outcomes from the telephone contact, itemised below:

- Outcome 1: for patients with any new neurological compromise, direct admission to oncology ward for urgent imaging (MRI whole spine unless contraindicated) and further management.

- Outcome 2: for patients with suspicious pain, but no neurological compromise, arrangements made for urgent outpatient review with urgent outpatient MRI of the whole spine.

- Outcome 3: for patients where symptoms are not suspicious for MSCC, arrangements made for routine review in clinic.

- Outcome 4: for patients with a very poor prognosis from underlying malignancy, or for those who have established paraplegia for over 48 hours where there is no prospect of recovery and who are in a stable environment with adequate nursing care, discussion with the patient/primary care team to explain the situation, avoiding a futile admission to hospital.

The inpatient pathway for ‘outcome 1’ patients was designed to streamline the initial assessment and management of patients and to ensure timely access to MRI (or CT if MRI is contraindicated) to assess the whole spine. It mandates that all patients are discussed between the oncology and spinal surgery team to ensure that a definitive management plan for MSCC can be made to ensure: 1) control of pain; 2) relief of the compression; and, 3) stability of the spine, where possible.

The initial plan for the guidance of ward staff is detailed in Box 2.

Box 2 NHS Grampian guidance for ward staff for the management of patients admitted with suspected malignant spinal cord compression

- Manage patient lying flat until spinal stability assessed clinically and on MRI.

- Assess for urinary retention and catheterise if required.

- Commence patient on dexamethasone (with PPI cover and daily blood glucose monitoring) with plan for steroid reduction in place as below:

- start at 8 mg b.d. (ideally 8 am and 2 pm);

- reduce to 4 mg b.d. after RT complete, for 4 days;

- reduce to 4 mg o.d. for 4 days;

- reduce to 2 mg o.d. for 4 days;

- reduce to 1 mg o.d. for 4 days;

- reduce to 0.5 mg o.d. for 4 days then stop; and,

- steroid dose should be increased in event of neurological deterioration.

- Consider the need for antiembolic graduated (TED) stockings.

- Consider the need for thromboprophylaxis (2,500 units dalteparin) – increasing the dose to 5,000 units if surgical approach not being considered.

- Consider the need for (increased) analgesia.

- Consider the need for bowel regimen.

- Arrange urgent MRI of whole spine, or if contraindicated, consider whole spine CT.

|

Following an MRI scan that reveals spinal cord compression, the oncology team complete a spinal instability neoplastic score (SINS; Table 1), which is a prospectively validated assessment of spinal stability based on the site of the compression, the presence and nature of pain, the nature of the metastases (sclerotic, mixed or lytic), the extent of involvement of the posterior elements of the spine and the degree of vertebral collapse and spinal misalignment.7 A score of 7 or more is suggestive of spinal instability. In addition, a prognostic score, the revised Tokuhashi score, is calculated to give an estimate of the patient’s prognosis (Table 2).8 The resultant score stratifies patients into groups with anticipated survival of <6 months, 6–12 months and >12 months. Clearly this provides a very rough estimate of prognosis and the judgement of an experienced clinician who is familiar with recent therapeutic advances and their impact on survival is paramount.

Table 1 Spinal instability neoplastic score (SINS)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Junctional (occiput–C2, C7–T2, T11–L1, L5–S1)

|

3

|

|

Mobile spine (C3–C6, L2–L4)

|

2

|

|

Semirigid spine (T3–T10)

|

1

|

|

Rigid spine (S2–S5)

|

0

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

3

|

|

No (occasional pain but not mechanical)

|

1

|

|

Pain-free lesion

|

0

|

|

|

|

Lytic

|

2

|

|

Mixed lytic/blastic

|

1

|

|

Blastic

|

0

|

|

|

|

Subluxation/translation present

|

4

|

|

De novo deformity (kyphosis/scoliosis)

|

2

|

|

Normal alignment

|

0

|

|

|

|

>50% collapse

|

3

|

|

<50% collapse

|

2

|

|

No collapse, with >50% of the body involved

|

1

|

|

None of the above

|

0

|

|

|

|

Bilateral

|

3

|

|

Unilateral

|

1

|

|

None of the above

|

0

|

Table 2 Revised Tokuhashi prognostic score8

|

|

|

|

|

|

Poor (10–40%)

|

0

|

|

Moderate (50–70%)

|

1

|

|

Good (80–100%)

|

2

|

|

|

|

≥3

|

0

|

|

1–2

|

1

|

|

0

|

2

|

|

|

|

≥3

|

0

|

|

1–2

|

1

|

|

0

|

2

|

|

|

|

Unremovable

|

0

|

|

Removable

|

1

|

|

No metastases

|

2

|

|

|

|

Lung, osteosarcoma, stomach, bladder, oesophagus, pancreas

|

0

|

|

Liver, gall bladder, unidentified

|

1

|

|

Others

|

2

|

|

Kidney, uterus

|

3

|

|

Rectum

|

4

|

|

Thyroid, breast, prostate, carcinoid

|

5

|

|

|

|

Complete (Frankel A, B)

|

0

|

|

Incomplete (Frankel C, D)

|

1

|

|

None (Frankel E)

|

2

|

|

|

|

|

0–8

|

6 months

|

|

9–11

|

6–12 months

|

|

12–15

|

Over 12 months

|

Once the MRI scan and the SINS and Tokuhashi scores are available, the patient’s case is discussed with the spinal surgery team on call and the decision over definitive management is made. In general, patients who are most likely to benefit from a surgical approach include those with a better prognosis, those with radioresistant tumours, those with a single site of MSCC with retained spinal integrity above and below the lesion, and those with good preservation of neurological function. Surgical interventions may include spinal stabilisation procedures (percutaneous pedicle screw fixation, cement augmentation) with or without excision of the tumour (via vertebral body resection or laminectomy). In select cases (typically with renal cancer metastases, which tend to be highly vascular) patients may require embolisation of the tumour mass prior to surgery to minimise the risk of haemorrhage. Postoperative radiotherapy is usually delivered to improve local control. For those patients in whom surgery is not feasible or appropriate, radiotherapy to the site of MSCC is usually delivered. In a small proportion of patients with MSCC (those with germ-cell tumours or lymphoma), primary chemotherapy may be the preferred definitive management approach.

Patchell et al. have published randomised evidence showing that in select patients, surgery followed by radiotherapy resulted in improved outcomes compared to radiotherapy alone, with independent mobility being better maintained in the surgery arm.9 A meta-analysis of comparative studies of radiotherapy vs surgery followed by radiotherapy, undertaken by Lee et al.,10 confirmed improved ambulatory outcomes, but also suggested a survival benefit at the 6- and 12-month time points in those patients undergoing combined modality treatment. These data strongly support an aggressive multimodality approach for patients of good performance status and with a good oncological outlook.

Multiple dose-fractionation regimens are in use for radiotherapy for MSCC, and although there is nonrandomised and randomised evidence in support of using a single 8 Gy fraction (demonstrating no significant difference compared to 20 Gy in five fractions in terms of symptom control and need for reirradiation in patients with a limited prognosis),11,12 many oncologists will choose a higher dose in a fractionated regimen for patients in whom the cancer and mobility prognosis is likely to be better.

In tandem with a definitive medical management plan for patients with MSCC, appropriate nursing and physiotherapy/occupational therapy planning is vital. Patients are managed flat until an MRI scan is performed, but early mobilisation for those with a stable spine is important to minimise the risks of prolonged recumbency in this population with advanced cancer, in particular, chest infection.13 Where the spine is unstable, lying flat is encouraged until surgical stabilisation can be achieved, or if this is not feasible, graded mobilisation is undertaken and the use of a spinal brace is considered in order to provide external support. For patients who are destined not to achieve independent mobility, early assessment for wheelchair use is undertaken. All patients require multidisciplinary input to ensure that discharge planning is started early, with involvement of orthotics, social work, rehabilitation teams and community teams of allied health professionals as appropriate.

In summary, MSCC can be a devastating diagnosis resulting in loss of independence in a patient’s final months of life, however, in many cases, early identification can allow early treatment to prevent paraplegia and loss of bowel/bladder function. The MSCC pathways that are developed in each UK cancer network are designed to identify a high-risk population, to provide information to allow such high-risk patients to identify early symptoms of the condition, and to empower patients and their primary care teams to seek early investigation of concerning symptoms through a single point of contact (the MSCC coordinator). Patients can then be triaged for immediate admission or outpatient investigation. As with all medical conditions, close liaison and good communication between all the relevant teams is paramount to achieving the best functional outcome for patients.

Presented in this paper is the NHS Grampian approach, however, many other MSCC pathway designs exist depending on regional services and local resources. Some pathways recommend the use of the Bilsky score to grade the degree of MSCC on MRI scan,14 and the NOMS framework (neurologic, oncologic, mechanical and systemic considerations) has been used to aid decision-making in MSCC.15 The key point is that all patients need access to a robust, sustainable, easily accessible pathway to prevent or minimise the consequences of this potentially devastating condition.

References

1 Lawrie I. Back pain in malignant disease – metastatic spinal cord compression? Rev Pain 2010; 4: 14–7.

2 Levack P, Graham J, Collie D et al. Don’t wait for a sensory level–listen to the symptoms: a prospective audit of the delays in diagnosis of malignant cord compression. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2002; 14: 472–80.

3 McLinton A, Hutchison C. Malignant spinal cord compression: a retrospective audit of clinical practice at a UK regional cancer centre. Br J Cancer 2006; 94: 486–91.

4 Metastatic spinal cord compression: diagnosis and management of adults at risk of and with metastatic spinal cord compression. Clinical guidelines CG75 November 2008. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg75/evidence/cg75-metastatic-spinal-co... (accessed 18/11/18).

5 Loblaw DA, Laperriere NJ, MacKillop WJ. A population-based study of malignant spinal cord compression in Ontario. Clin Oncol 2003; 15: 211–7.

6 MacMillan Cancer Support. Malignant spinal cord compression. Information for patients; 2015. http://be.macmillan.org.uk/Downloads/CancerInformation/LivingWithAndAfte... (accessed 18/11/18).

7 Fisher CG, Schouten R, Versteeg AL et al. Reliability of the spinal instability neoplastic score (SINS) among radiation oncologists: an assessment of instability secondary to spinal metastases. Radiat Oncol 2014; 9: 69.

8 Tokuhashi Y, Matsuzaki H, Oda H et al. A revised scoring system for preoperative evaluation of metastatic spine tumor prognosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005; 30: 2186–91.

9 Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF et al. Direct decompressive surgical resection in the treatment of spinal cord compression caused by metastatic cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet 2005; 366: 643–8.

10 Lee CH, Kwon J, Lee J et al. Direct decompressive surgery followed by radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for metastatic epidural spinal cord compression: a meta-analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014; 39: E587–92.

11 Rades D, Huttenlocher S, Segedin B et al. Single-fraction versus 5-fraction radiation therapy for metastatic epidural spinal cord compression in patients with limited survival prognoses: results of a matched-pair analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2015; 93: 368–72.

12 Hoskin P, Misra V, Hopkins K et al. SCORAD III: randomized noninferiority phase III trial of single-dose radiotherapy (RT) compared to multifraction RT in patients (pts) with metastatic spinal canal compression (SCC). J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 18_suppl, LBA10004.

13 Pease NJ, Harris RJ, Finlay IG. Development and audit of a care pathway for the management of patients with suspected malignant spinal cord compression. Physiotherapy 2004; 90: 27–34.

14 Bilsky MH, Laufer I, Fourney DR et al. Reliability analysis of the epidural spinal cord compression scale. J Neurosurg Spine 2010; 13: 324–8.

15 Laufer I, Rubin DG, Lis E et al. The NOMS framework: approach to the treatment of spinal metastatic tumors. Oncologist 2013; 18: 744–51.