Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

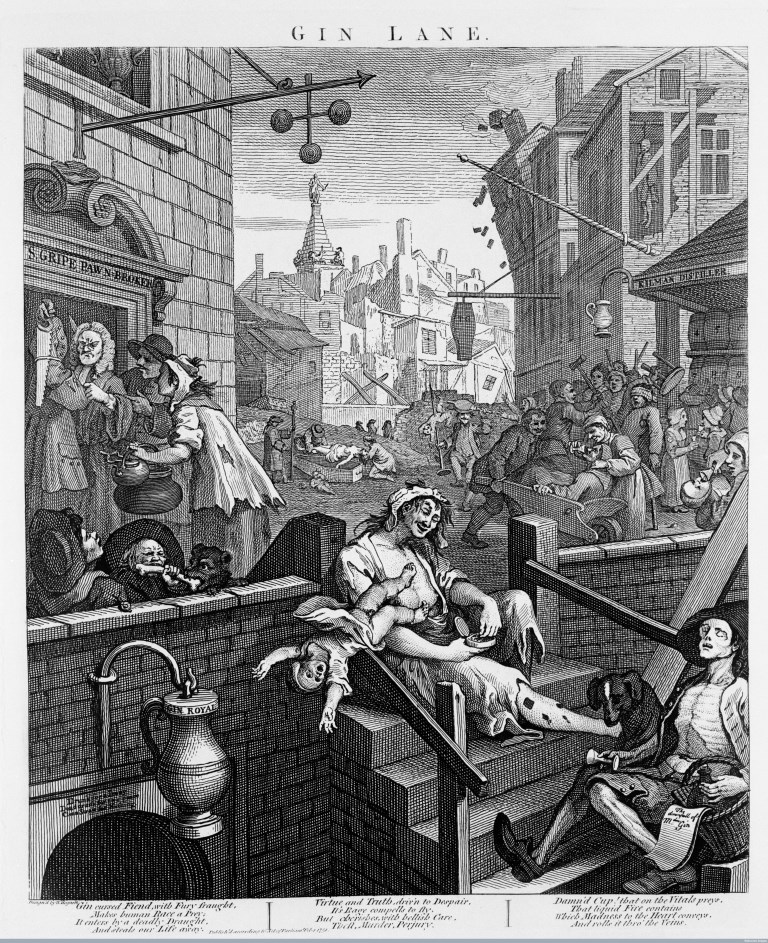

Gin cursed Friend, with Fury fraught,

Makes human race a Prey;

It enters by a deadly Draught,

And steals our Life away.

Virtue and Truth, driv'n to Despair,

It's Rage compells to fly,

But cherishes, with hellish Care,

Theft, Murder, Perjury.

Damn'd Cup! that on the vitals preys,

That liquid Fire contains

Which madness to the Heart Conveys

And rolls it thro' the Veins.

These verses, written by William Hogarth's friend and collaborator, the Rev. James Townley, accompany the artist's print, Gin Lane. Alcohol abuse is hardly a uniquely modern problem - Hogarth's print depicts the results of such abuse in the eighteenth century and highlights many of its social consequences.

Hogarth was interested in many humanitarian projects leading to reform and his zeal with regard to social and moral problems continued throughout his life. Many aspects of these problems appear in his works, which draw attention to the evils portrayed in the hope that some effort might be made to remedy them. As such, exaggeration of events would seem to be portrayed for enhanced effect. Nevertheless, exaggeration does not necessarily imply unreliability with regard to the underlying situation. To demonstrate the various effects of a social problem within the confines of one print it was appropriate to illustrate as many of them as possible in order to convey the breadth of the problem within the affected society. This is the case in the portrayal of Gin Lane (1751).

Figure 1, Gin Lane 1750-1751 by William Hogarth (© Wellcome Images, Wellcome Library, London).

Gin, whilst not the elixir of life that was looked for, was widely regarded as an universal panacea. If the outside world only offered hardship in the form of dirt, disease and poverty, the inner man could at least be cheaply and quickly fortified with the juice of the Juniper berry. Gin was introduced into England by soldiers returning from the Low Countries early in the eighteenth century and its popularity increased rapidly and disastrously between 1720 and 1750 especially in London, although other trading cities such as Manchester and Bristol were not spared.

It was not taxed initially because the use of fermented barley in its composition provided a market for farmers, and because the distillers had a powerful political voice. Its price therefore was low and its consumption overtook that of the traditional beverage of beer or ale as the favourite drink amongst the working class and poorer members of society. The more wealthy and aristocratic members of society drank wine, brandy or punch. Drunkenness was not seen as a vice in society as a whole. Its consequences were. The first attempt at legislation was in a Parliamentary Bill of 1729 which required each retailer to take out a licence costing £20, and put a duty of 5s. per gallon on gin. The result of this was to suppress the distillation of good gin and to increase the production of inferior products known then as 'Parliamentary Brandy'.1

A Bill of 1735 imposed taxes and licence charges upon retailers in a further attempt to curtail the distribution of gin. The preamble to this Act stating the necessity for it began:

Whereas the Drinking of Spirituous Liquors or Strong Waters is becoming very common, especially amongst the People of lower and Inferior Ranks, the constant and excessive Use whereof tends greatly to the Destruction of their Healths rendying them unfit for useful Labour and Business, Debauching their Morals, and inciting them to perpetrate all manner of Vices. . .2

The Act itself provided further impositions which caused anger amongst the admirers of the product and there was difficulty in enforcing the law. Gin continued to be sold by other names, including 'Ladies Delight', 'Cuckold's Comfort', 'King Theodore of Corsica' and 'Strip-me-Naked'. In 1743, the Act was repealed,...

whereas great Difficulties and Inconveniences have attended the putting the said Act in Execution, and the same hath not been found effectual to answer the Purposes thereby intended. . .3

Other duties were imposed, but the Vices alluded to in the Act of 1735 continued; the crime rate increased and this, along with poverty and ill-health, was blamed on the consumption of gin.

In 1751, Corbyn Morris, an economic reformer who initiated plans for a general registry of the total population of Great Britain and of the annual increase and decrease by births and deaths, invited people to:

Enquire from the several hospitals in the City, whether any increase of patients and of what sort, are daily brought under their care? They will declare, increasing multitudes of dropsical and consumptive people arising from the effects of spirituous liquors.4

Henry Fielding, a friend of Hogarth's, who became a lawyer and a Westminster magistrate in addition to pursuing his career as a dramatist and author, wrote a tract in 1751 entitled Enquiry into the Causes of the late Increase of Robbers etc. with some proposals for remedying this growing evil.5 In the second section of this he drew attention to the evils associated with the consumption of gin, 'This odious Vice (indeed the Parent of all others) first introduced by the Danes.' He continued:

A new kind of Drunkenness is lately sprung up amongst us-which-if not put a stop to, will infallibly destroy a great Part of the inferior People... the intoxicating Draught itself disqualifies them from using any honest Means to acquire it, at the same time that it removes all Sense of Fear and Shame and emboldens them to commit every wicked and desperate Enterprise. . .

What must become of the Infant who is conceived in Gin? with the poisonous Distillations of which it is nourished both in the Womb and at the Breast.

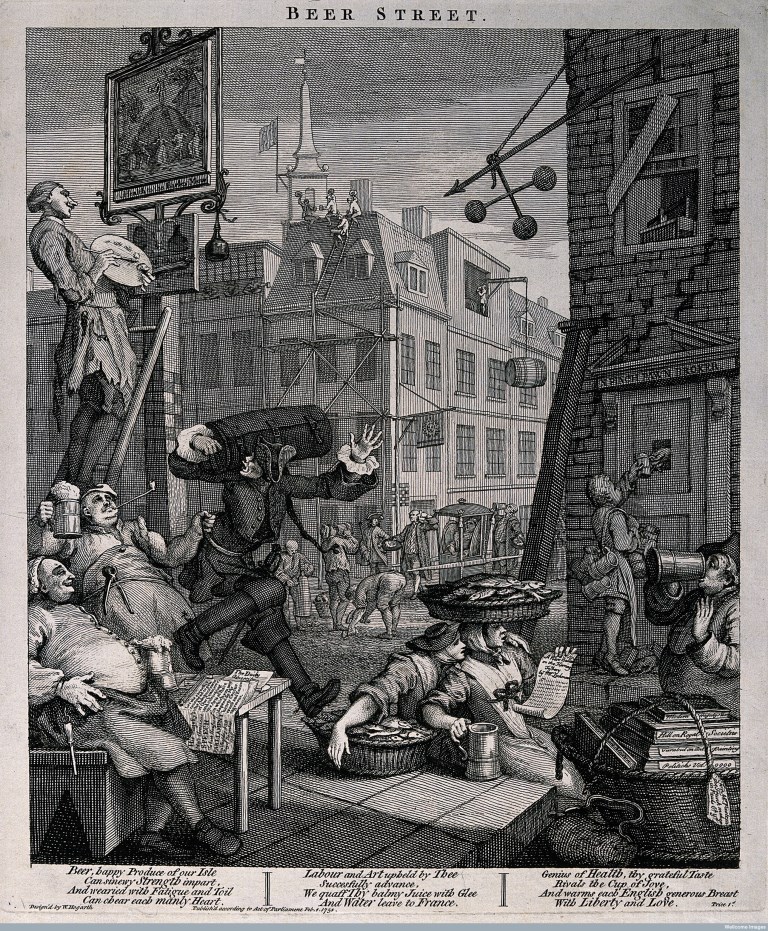

Figure 2, Beer Street 1750-1751 by William Hogarth (© Wellcome Images, Wellcome Library, London).

Hogarth's thoughts on these matters were in line with those of his friend and his prints Beer Street and Gin Lane constituted part of a general attempt to reimpose legislation on the sale of spirits. In Gin Lane, Hogarth points graphically to the total disintegration of a well-ordered society such as that depicted in Beer Street. He compares one with the other indicating that the difference is due to the consumption of gin rather than the traditional English beer (Fig. 2). Publication of the prints was announced on February 13, 1751 in the General Advertiser along with other prints of topicality with the author's comments,

As the Subjects of those Prints are calculated to reform some reigning Vices peculiar to the lower Class of People.

A pamphlet entitled A Dissertation on Mr. Hogarth's Six Prints lately Publish'd contributed to contemporary comment on the subject.6 This pamphlet was inscribed to the 'Lord Mayor, City of London and Worshipful Court of Aldermen' (1751) and contained a 'Genuine Narrative of the horrible Deeds perpetrated by the fiery Dragon, GIN...' In the Dissertation, the Bishop of Worcester asks,

...whether the criminals themselves and the crouds [sic] that sometimes attend them, do not bear in their countenance and their whole manner and Appearance, the plainest and most shocking Proofs that their Blood is inflamed by the habitual drinking of Gin...Their infants wretched, half-naked tho' in the coldest weather, and half starved for want of proper Nourishment; for so indulgent are these tender Mothers, that to stop their little gaping mouths, they will pour down a spoonful of their own delightful Cordial...

Look on her Children, and you will see such a Parcel of poor little diminutive Creatures, that you will fancy yourself in the Country of the Pigmies... either they were begot with very ill Will, or that there was some Defect in the generative Powers of their Parents; one is bandy-legged, another hump-back'd, another goggle-eyed, another with a Monkey's Face, scarce one in its proper shape, and all of them wearing some visible mark of their Mother's Folly.

Hogarth's scene is set in the slum district of St Giles' Parish, Westminster, where in 1750 at least every fourth house was a gin-shop, and numerous brothels and places for receiving stolen goods existed. The only thriving establishments appear to be the pawnbroker's where the prosperous looking owner 'Mr Gripe' (the name was slang for a usurer), is profiting from the search for funds to support the more profligate habits of his clients, and the distillers. This state of affairs accords with the observations of a letterwriter to the Gentleman's Magazine in 1743, who wrote:

Since Spirituous Liquors became common, the Baking Trade has very much decreas'd and what the Landed Interest has gained by them, it has lost in Bread and Beer; besides Meat, Butter, Cheese and other Eatables... [Spirituous Liquors] obstruct the carrying on of Trade in every Branch...7

The church tower in the background signifies the position of the church, or of some of its incumbents, in relation to the conditions around them. The 'goodness' they profess is at a distance and difficult to reach. The inhabitants of this scene illustrate collectively the effects that addiction has on life. The careless woman in the centre of the picture allows her underclothed child to fall presumably to its death whilst she takes a pinch of snuff. She herself suffers from intoxication, neglect and probably syphilis-indicated by the sores on her legs. The baby shows signs of the 'fetal alcohol syndrome' resulting from maternal alcoholism, but not recognised as such before the present century. Hogarth's observational powers provide this infant with seemingly large round eyes situated between small palpebral fissures, lending what has been called an 'Orphan Annie' appearance to the face.8 Small cheek-bones and small chin, an undersized head, some degree of mental retardation, low birth weight and stunted growth form other features of the condition, providing an 'elfin-type' study not unlike Hogarth's infant who is 'wearing some visible mark of [its] Mother's folly'. Whilst not recognising this syndrome as such, Hogarth and Fielding amongst others, seemed to observe congenital effects of maternal alcoholism.

Unhappy mothers habituate themselves to these distilled liquors, whose children are born weak and sickly, and often look shrivel'd and old as though they had numbered many years.9

The baby to the right of the steps in Gin Lane (Fig 1) is being fed on gin, whilst next to the coffin in the mid-ground, a weeping infant illustrates another form of neglect. Close by, a child is impaled on a large skewer, an example of eighteenth century 'non-accidental injury' attributed to gin mania, not so termed at that date but prevalent by any name and attested to by the perceived need to establish the Foundling Hospital at that time.10

No expedient has yet been found out for preventing the murder of poor miserable infants at their birth, or suppressing the inhuman custom of exposing newly-born infants to perish in the streets; or the putting of such unhappy foundlings to wicked and barbarous nurses who. . . do often suffer them to be starved for want of due sustenance or care...

The cadaverous ballad singer in the foreground is, or was, an itinerant ballad seller. He was supposedly painted from a man who frequented the area whose cry was 'Buy my ballads, and I'll give you a glass of gin for nothing'.11 The ballad for sale is entitled 'The downfall of Mdm Gin'. His dog is shown looking at the overturned glass with interest but appears to be healthier than his master who has parted with most of his clothes and his flesh to support his gin-drinking habit.

Two charity-girls or orphans, so designated by badges inscribed GS on their sleeves representing St Giles' Parish, indicate the youthfulness (and lack of supervision) of some imbibers. This was a pointed reference to such Charity Schools which failed in their professed objective of preserving children from vagrancy and fitting them for some sort of regular work. A woman lies in a drunken stupor on the left hand side of the steps with a snail crawling over her- indicating that she has been in this condition for some time.

In Gin Lane, Hogarth presents alcoholism as a social and economic problem, his visual images providing powerful 'propaganda' points. Clinical signs are also apparent, provided by this acute observer of physiognomy and pathognomy. Although retrospective diagnosis of many of the problems presented is fraught with inaccuracies, the overall effects of the consumption of gin were widespread and noted by many able observers.

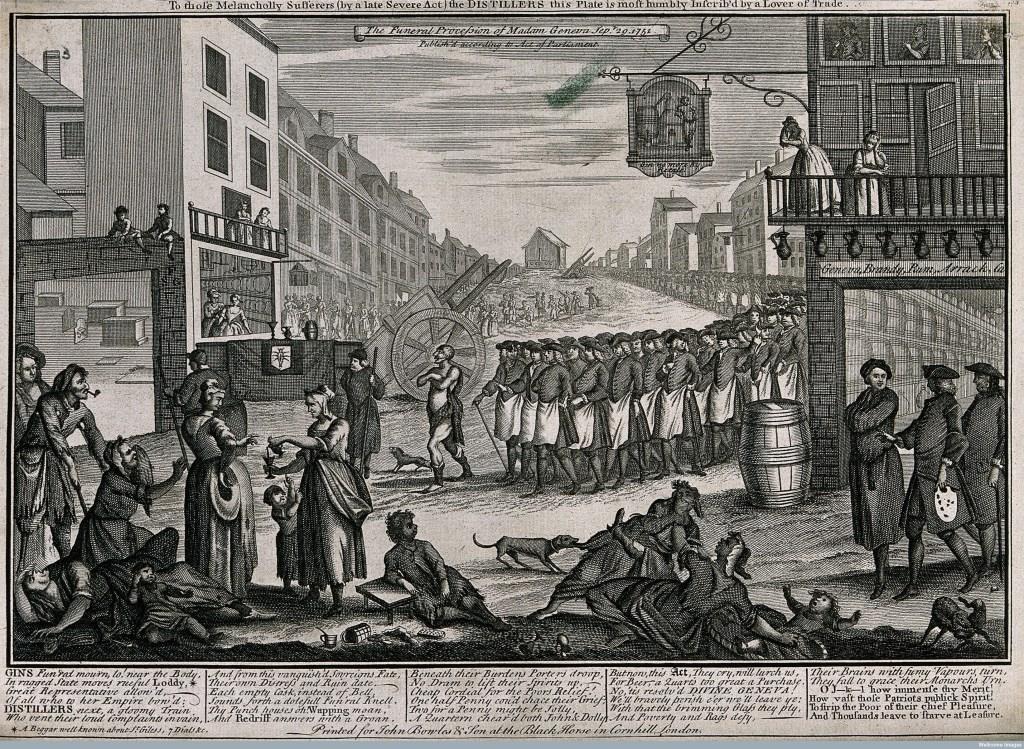

Figure 3, The funeral procession of Madam Geneva 1751 (© Wellcome Images, Wellcome Library, London).

In response to petitions from physicians, magistrates' committees, clergymen and private citizens, the government introduced legislation which was enacted in 1751. This restricted licensing of premises and imposed further duties on the sale of spirituous liquors. Infringements were more rigorously checked and penalties incurred. Gradually the problem diminished, but not without some outcry from those who, for various reasons disliked these measures. The 'Funeral Procession of Madam Geneva' was advertised as follows on September 29, 1751:

To those Melancholy Sufferers (by a late Severe Act) the DISTILLERS this Plate is most humbly Inscrib'd by a lover of Trade. 12

This was an engraved plate (Fig 3) of a street in St Giles's, London with a coffin on which lies a glass, noggin (a small mug or wooden cup which could hold a dram of alcoholic liquor of about a gill or quarter of a pint measure) and a key, being borne to a burial ground. It is followed by a poorly clad 'Loddy' described below as a 'Beggar well known about St Giles's, Seven Dials etc.', and a procession of publicans. Verses underneath include the lines:

GINS Fun'ral mourn, lo!...

Cheap Cordial for the Poors Relief!

One half Penny cou' d chace their Grief...

Hogarth, on his own admission, wished to draw attention to various social and moral issues in society. He would have had nothing to gain and much to lose by misrepresentation of facts with regard to these issues. Although his interpretations of the facts might differ from that of other witnesses, they had to be seen to be realistic. By co-ordinating his graphic images with those images provided by his literary contemporaries and in medical writings of the time, it can be seen that they represent a realistic scenario with regard to the prevailing medical scene and to some of the opinions expressed at the time. Hogarth offers a well-informed layman's view of the world of medicine as it impinged on the society that he portrayed. Alcohol abuse is just one example.

REFERENCES

1. Coffey TG, 'Beer Street: Gin Lane: Some Views of 18th-Century Drinking'. Q J Stud Alcohol 1966; 27: 674.

2. An Act for laying a duty upon the Retailers of Spirituous Liquors, and for licensing the Retailers thereof to be enacted after 29, September, 1736.

3. An Act for repealing certain Duties on Spirituous Liquors, and on Licences for retailing the same, and for laying other Duties on Spirituous Liquors and on Licences to retail the said Liquors, Act of Parliament 1743.

4. See reference 1 p. 671.

5. Fielding, Henry. Enquiry into the Causes of the late Increase of Robbers etc., London, 1751.

6. A Dissertation on Mr. Hogarth's Six Prints Lately Publish'd inscrib'd to the Lord Mayor, City of London and Worshipful Court of Aldermen, 1751.

7. Gentleman's Magazine, Vol. XIII, Jan. 20 1743: 38.

8. Rodin, Alvin E. Infants and gin mania in 18C. London, JAMA, 1981; 245: 1237.

9. A report from the Middlesex Sessions Committee in 1735.

10. George, M Dorothy. London Life in the Eighteenth Century, Penguin Harmondsworth, Middlesex, 1925: 56.

11. Ireland, John. Hogarth Illustrated, 1791; ii: 330.

12. Printed for John Bowles & Son at the Black Horse in Cornhill, London, Sept. 20, 1751.

Previously published in the Proceedings of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (1992), 22: 74-80

Author: Fiona Haslam, Clinical Assistant in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Bolton General Hospital.

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources