Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

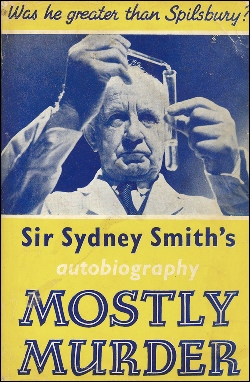

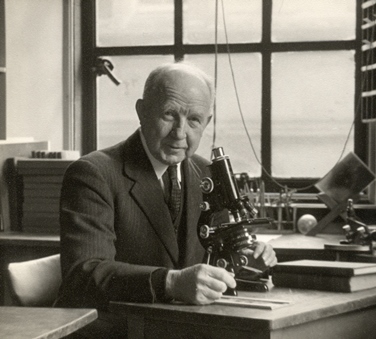

Sir Sydney Smith (1883-1969) was one of the pre-eminent medico-legal specialists of his day. As a leading forensic pathologist, Professor of Forensic Medicine and Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh from 1928 until his retirement in 1953, his medico-legal skills were well known.

In the 1930s, when forensic science was yet to be professionally differentiated from forensic medicine, Smith developed considerable expertise in forensic analytical laboratory techniques in areas that would now be the domain of a variety of scientific specialists. He took a keen interest in forensic ballistics. Indeed, while he was Medico-Legal Expert for the Egyptian Government, before his Edinburgh appointment, he and his colleagues identified the gun which was used to assassinate Sir Lee Stack Pasha (Sirdar or Commander in Chief of the Egyptian Army and Governor General of Sudan) in 1924, one of the first such identifications in legal history and a landmark case in the history of forensic ballistics. Therefore, it was small wonder that Lord Trenchard, Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, should beat a path to Smith’s door to consult him on the set up of a new laboratory for the Metropolitan Police in 1934. Smith’s autobiography, Mostly Murder reprints Trenchard’s first letter to Smith on this matter, gives a brief account of Trenchard’s laboratory project and Smith’s advice. Trenchard offered him the post of Director but Smith felt that he could not leave Edinburgh at that time.

It has been suggested that ‘the comparatively modest salary on offer’ was not sufficient to entice Smith to take up the role (nor indeed his counterpart in the University of Glasgow, Professor John Glaister Jr, who was also approached). However, seven letters from Lord Trenchard to Professor Smith sent over the summer of 1934 and held in the Royal College of Physicians Edinburgh archive suggest that Smith actively considered accepting the directorship and his reasons for finally rejecting it, despite his clear interest in police laboratories, were rather more complex than the matter of the salary. Only the Trenchard half of the correspondence is held in the RCPE archive, however it is not difficult to infer the questions which Smith posed to Trenchard in relation to the terms and conditions of the laboratory directorship. As Trenchard marked his letters ‘Strictly Confidential’ or ‘Personal and Confidential’ and sent them to Smith’s home address, it was clear that he did not want his plan to ‘poach’ Smith to be known to Edinburgh University. The salary on offer was £1700 per annum. This sum equates to about £110,000 in today’s terms. As the salary attaching to the position was not mentioned in Trenchard’s subsequent letters it is reasonable to infer that the salary was not the main issue that prompted Smith to turn down the offer.

Rather the two concerns which Smith raised with Trenchard were (a) the potential involvement of London University in the Metropolitan Police laboratory project and (b) retirement age and pension. To the former concern, Trenchard responded that, in the interests of speed he had not yet approached university authorities. ‘I must first start this Laboratory and try, if possible, to bring the University of London in later.’ On the second point Trenchard responded that, as the requirements were clearly of a permanent nature, he did to believe there would be any question of retirement before the age of sixty.

Understandably, Smith must have felt that the post offered little scope for the kind of research facilities he enjoyed at Edinburgh, given that no one in the University of London had even been contacted about the set up of the new laboratory at that stage. In addition, although Trenchard and Smith corresponded on the minutiae of pension arrangements over the summer of 1934, despite the offer of a generous salary, Trenchard could offer only vague promises on retirement arrangements and pension which hardly matched up to the life tenure and superannuation which Smith enjoyed at the University of Edinburgh. Whatever the temptations of becoming the inaugural director of the Metropolitan Police Laboratory, Smith was not to be persuaded.

In the relatively short time that he was Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police Trenchard had made a number of significant reforms and was desperate to start up a Police College at Hendon where the new laboratory was to be be sited and where courses of instruction could be given to detectives by laboratory staff. His letters betray a tone of considerable urgency; he needed to get detective courses started at the Police College within a year. Indeed, as he explained to Smith: ‘I am an old man in a hurry’. But perhaps he was an old man in too much of a hurry. Sensing that he was unlikely to hook his big fish, Smith, with somewhat meagre bait, he urged him to suggest someone more junior instead. ‘I must get a more junior man to start my laboratory with a view to getting a really first class man later.’ The appointment of the junior man took place and it was with some relief that Trenchard wrote to Smith on 17th November to inform him that Smith’s suggested ‘junior man’, Dr Davidson had been appointed. Unfortunately, as it subsequently turned out, Dr Davidson’s appointment was not a great success and the laboratory floundered in its early years.

However, the story of Sir Sydney Smith’s interest in directing a police laboratory does not end there. A few hundred metres from the RCPE premises in Queen Street, Edinburgh a file of Scottish Office memos, housed in National Records Scotland, reveals that Sir Sydney Smith also argued for the setup of a police forensic laboratory for Scotland, under his directorship at the University of Edinburgh a few years later.

In 1939, civil servants in the Scottish Home and Health Department (SHHD - part of the Scottish Office) began to discuss the adequacy of forensic science provision in Scotland. This was provoked, at least in part, by a letter from Professor Sydney Smith to the Lord Advocate (the highest legal officer in Scotland) offering to host a national police forensic laboratory under his aegis at the University of Edinburgh and suggesting preliminary costings. Senior police officers may well been discussing forensic laboratory facilities in Scotland for some time, but it was Smith’s letter to the Lord Advocate which appears to have unleashed a flurry of memos between civil servants prompting them to review forensic provision in Scotland. We should note that, in addition to the Metropolitan Laboratory, a regional forensic science network of laboratories in England and Wales was being developed under Home Office control in the 1930s. Of course, policing in Scotland lay outwith the Home Office remit so Scotland was not included in the new regional forensic science network. The frequent references in SHHD memos on forensic science to the apparently better provisioned situation for the subject in England and Wales show that Scottish civil servants were aware that the forensic laboratory situation was somewhat different south of the border. Smith’s suggestion presented itself as an apparently ‘off-the-shelf’ solution to growing requirements for forensic laboratory facilities in Scotland. It must be recalled that, government departments for Scottish affairs only gradually moved to Scotland in the first half of the twentieth century and the start of formal discussion on the provision of forensic matters in the Scottish Office coincided with its move to the splendid new St Andrew’s House which opened its doors on Calton Hill, Edinburgh on the site of the of the old Calton Jail, the day after war was declared in 1939.

For Smith, the appeal of setting up such a laboratory was clear. At a time when the distinction between forensic science and forensic medicine was crystallizing, he maintained an impressive array of knowledge and competence right across the forensic science spectrum, extending well beyond the medical arena. This made him a very attractive candidate for directorship of such a laboratory. The development of a forensic laboratory at the university would have allowed him to stay in Edinburgh, maintaining his more favourable employment conditions and, importantly, it would have given him continued access to laboratory research facilities which had not been on offer under the Metropolitan laboratory arrangement. But Smith’s Edinburgh police laboratory was not to be. The outbreak of war put an end to Scottish Office discussion on Scottish forensic facilities and when the matter was re-opened after the war, there was no further discussion of Smith’s proposed university laboratory in Scottish Office memos and the provision of police forensic laboratory facilities in Scotland took a different turn. Nevertheless, Smith’s acknowledged expertise and advice had acted as something of a catalyst in the development of forensic science laboratories both north and south of the border.

References

1 Smith, 1959, Ch.7

2 Smith, 1959, pp. 220-1

3 Ambage and Clark, 1994, p. 299

4 DEP/SMS/1/1/37

5 Letter from Trenchard to Smith, 15th June, 1934

6 Letter from Trenchard to Smith, 15th June, 1934

7 Letter from Trenchard to Smith, 15th June, 1934

8 Letter from Trenchard to Smith, 7th July, 1934

9 Letter from Sydney Smith to the Lord Advocate, 10th January, 1939, SRO HH55/711

Bibliography

Ambage, N. and Clark, M. ‘Unbuilt Bloomsbury: medico-legal institutes and forensic laboratories in England between the wars’, pp293-313, Legal Medicine in History, ed. M Clark and C. Crawford, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Smith, S., Mostly Murder, London, Harrap, 1959.

Smith, S., RCPE archive, DEP/SMS/1/1/37

SRO HH55/711 Scottish Office, Identification of Criminals, Laboratory Facilities in Scotland, National Records of Scotland.

Author: Alison Adam, Professor of Science, Technology and Society, Sheffield Hallam University and author of A History of Forensic Science: British beginnings in the twentieth century, Abingdon, Routledge, 2016.

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories