Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

Sir Alexander Morison (1779-1866) was an early forensic psychiatrist who specialised in mental and cerebral illness. After studying at Edinburgh’s Royal High School and the University of Edinburgh, he joined the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh where he practised for some years before moving south. While in England, Morison worked as Physician of Lunatic Asylums in Surrey and Bethlehem Hospital, and in 1838 became the personal physician to Princess Charlotte and her husband Prince Leopold. Following his knighthood and still working in London, Morison was appointed President of the RCPE, a position which he served from 1827 to 1829. Wishing to return to Edinburgh but without an official job offer or position, Morison gave a series of very popular lectures on mental illness, medical treatment, and physiognomy.

Morison’s 1840 publication, The Physiognomy of Mental Diseases, which includes some of his famous lectures, is of particular interest due to the inclusion of several plates featuring patients Morison encountered throughout his career. Morison believed that it was possible to diagnose mental illness by looking at patients’ faces and body language. He taught that there were “characteristic features” of the face which could be recognised to distinguish between different diagnoses and used to warn of “the approach of the disease” in people who might, he said, be predisposed to becoming ill. According to Morison, the face was a mirror of the state of the mind, and the muscles in the eyes and facial expressions could be very telling.

The study of the features of the face, or of the form of the body generally, as being supposedly indicative of character; the art of judging character from such study.

The College library and archives hold collections of Morison’s publications and the drawings he commissioned. The collection of original drawings were presented to the library by Sir Alexander Morison in 1862. Featured below are some of the striking images of patients suffering from mental illnesses, split into Morison’s four categories: Mania, Monomania, Dementia and Idiocy. The terms used here are taken from Morison’s 1838 work, based on the contemporary thought of the day, and do not reflect modern medical practice or opinion.

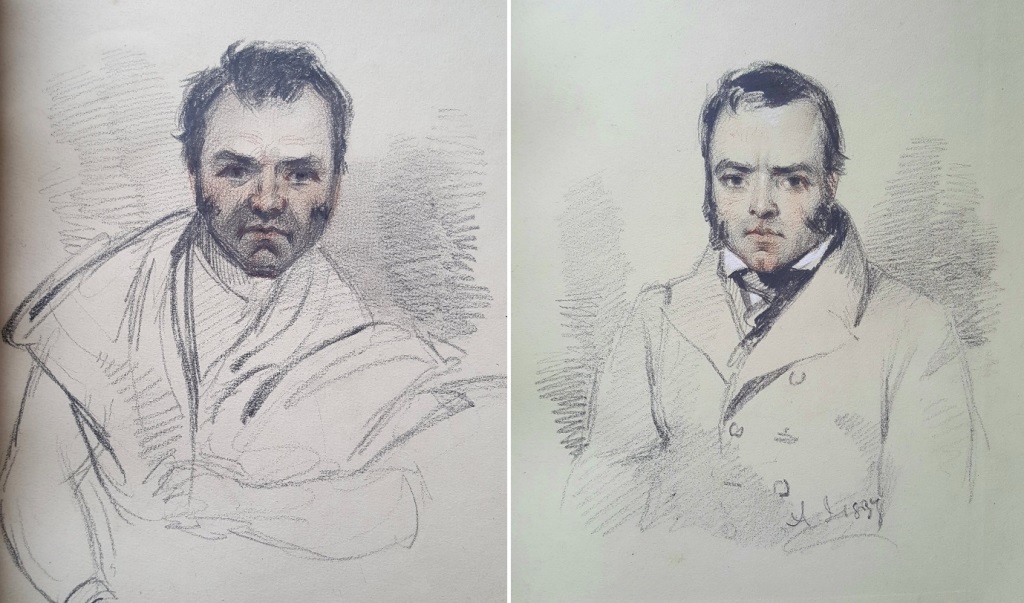

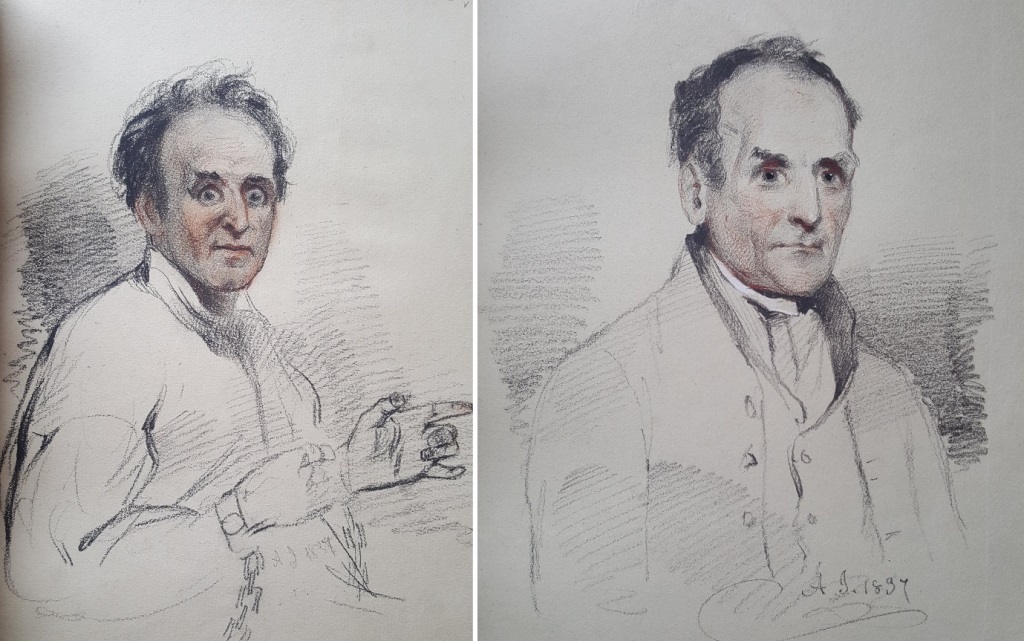

According to Morison and other nineteenth-century psychiatrists, Mania included symptoms such as excited imagination, lack of attention span, poor judgement, violent emotions, impulsiveness, restlessness, and insomnia. The drawings of patients with Mania were designed to showcase the “peculiar expression of the countenance and eyes”.

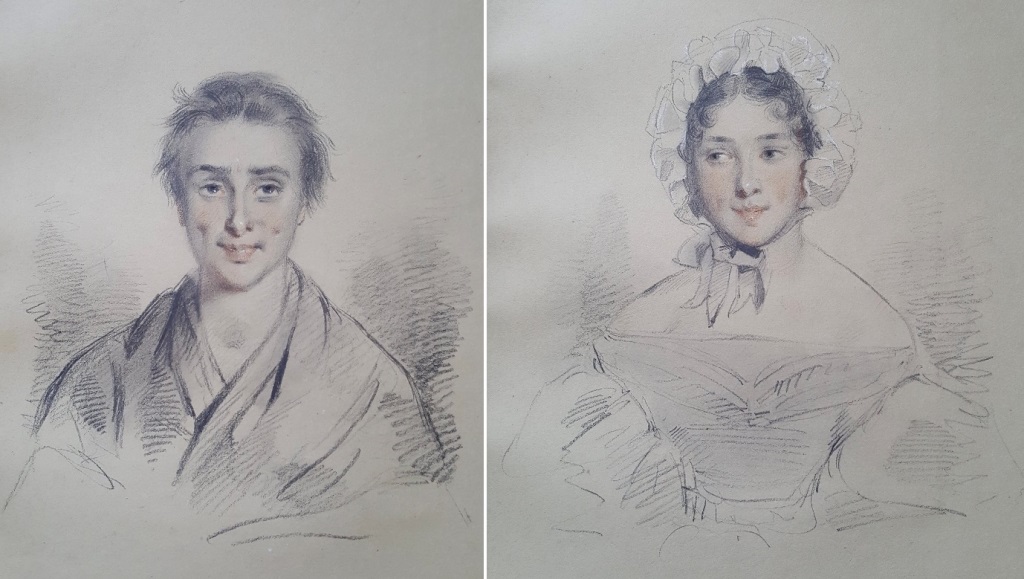

The above drawings show the same patient, F. W., suffering from an attack of Mania on the left and “in his sane state” on the right. The patient was described as suffering from frequent attacks of “violent rage and fury,” and had killed someone during one of his ill periods. The drawings are by A. Johnston and are captioned “intermittent mania – very violent” (left) and “recovered – remains well for one or more years” (right).

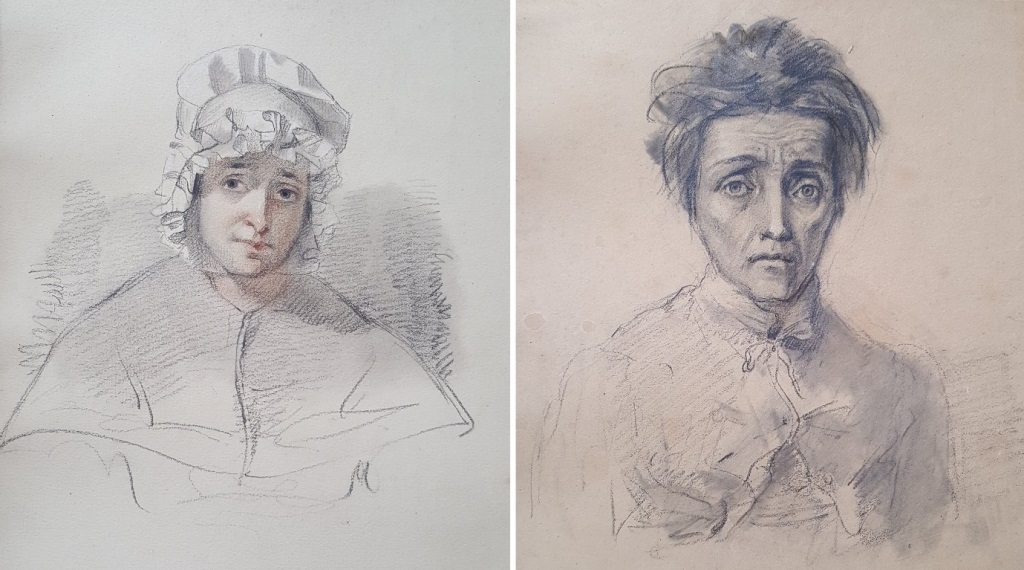

The above drawings display patient A.H. of Bethlem, aged 60, who was subject to periods of Mania and epilepsy. Morison found that in most cases Mania was aggravated by epilepsy, but with this patient, his extremely noisy and violent periods of Mania abated after fits of epilepsy. A. Johnston’s 1837 drawings were captioned as “Mania – Excited . . . committed murder” (left) and “lucid interval” (right).

Morison was opposed to the term Melancholia, believing that such a diagnosis was often incorrectly given when the patient was grieving or desolate but not actually ill. Instead of classifying mentally ill patients as melancholic, he used Dr. Esquirol’s label Monomania, which is defined as “a form of mental illness characterized by a single pattern of repetitive and intrusive thoughts or actions.” Within The Physiognomy of Mental Diseases, Morison described Monomania as a form of mental illness where the mind is affected by peculiar overwhelming ideas, such as love, fear, and grief. According to Morton, Monomania was the most prevalent mental illness, often co-occurring with other disorders. In terms of physiognomy, those diagnosed with Monomania were described as having a fixed and focused expression due to their obsession with whatever was occupying them at that moment.

The following patients were both diagnosed with what Morison referred to as Monomania with Love: Erotomania when they were overly sentimental, and Nymphomania or Satyreasis when they became overly sexual. The first set of images show an unnamed “elderly female, in whom lascivious ideas predominated”. She was diagnosed with Nymphomania and was admitted to Aberdeen Asylum. On the left is the original drawing, with the plate which features in The Physiognomy of Mental Diseases on the right. The drawing is unsigned and its artist is currently unknown, but the plate was engraved by W. H. Lizars.

The patient below, M.S.P. aged 22, was highly educated and worked as a governess until she developed a delusion that she was the Virgin Mary, pregnant with the Holy Ghost. She was diagnosed with Erotomania and admitted to Bethlem. Only the picture on the left is included in The Physiognomy of Mental Diseases, but Morison’s collection of drawings includes an additional sketch of patient M.S.P., “recovered in five months” (right). Both drawings have been attributed to A. Johnston.

The following patients were diagnosed with Monomania with Fear. Patients with this disorder were described as being afraid of one or more objects, afraid of everything, or filled with “a vague and undefined terror”. Many patients with this illness were thin, weak, restless and anxious due to their fears. The patient on the left, M. A. R, aged 40, believed that she saw dead people and was afraid of hurting her husband. She recovered after 18 months in Bethlem. The patient on the right, unnamed, was diagnosed with Panaphobia, due to her fear of every object and person. She was under constant watch in St. Luke’s in case she harmed herself. The left drawing is by A. Johnston, and the right by Rochard.

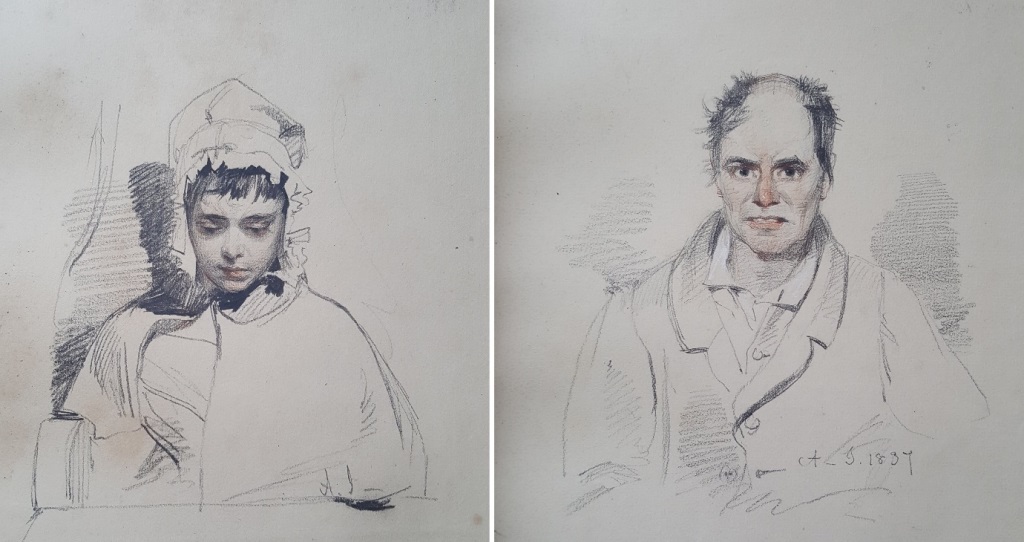

Monomania with Grief is the condition which was previously termed as Melancholia, and what would now be referred to as depression. According to Morison, this was one of the most common mental illnesses, and had a well-defined physiognomy with contracted facial muscles; sad, suspicious or scared expressions; and eyes often pointed to the ground.

The patient on the left, A. K., aged 20, was diagnosed with Monomania with Grief attributed to overzealous religious study. She never spoke and would not move at all without encouragement, but there was hope for her recovery. The patient on the right, T. C., aged 50, was determined to commit suicide after a dramatic change in financial circumstances. Both patients were at Bethlem and the drawings have been attributed to A. Johnston.

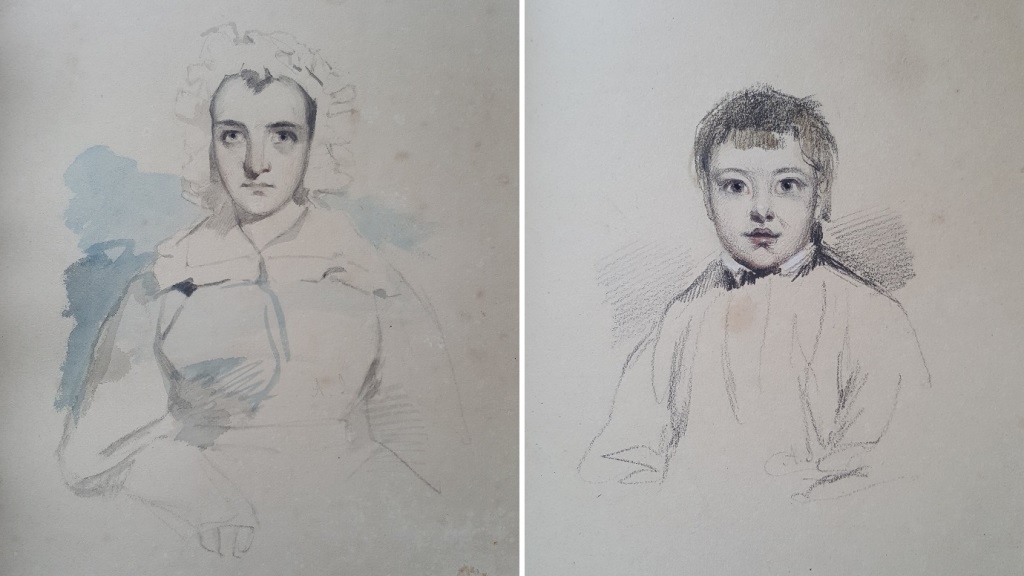

According to Morton and his peers in 1838, Dementia and Idiocy were terms used to describe the mind when “its manifestations are enfeebled or abolished”. According to Scottish clergymen, 3,495 of 4,647 mentally ill patients suffered from Dementia-like illnesses. The term Dementia was used when the mind was “previously in a sound state,” and Idiocy when the state remained the same from birth or a young age. The term Dementia was used equally for patients whose mental facilities deteriorated after trauma and those who were treated after they had reached old age. Those suffering from Dementia illustrated within Morton’s book were found to have relaxed features, unfocused eyes, and sometimes a shocked expression. Those termed as having Idiocy were described as having vacant expressions with wandering eyes and restless bodies.

The patient on the left, E. W., aged 24, was diagnosed with Dementia caused by terror. She would not speak or move, though she accepted food, and may have stayed silent throughout her stay in the asylum had a Bible not been accidentally placed in her hand. She was described to have read a few verses almost without thought and walked up and down the hall, but this action gradually faded and she returned to her previous state. The patient on the right, J. A., 9 years old, was diagnosed with Idiocy. He was described as being “good-tempered, though, at times, a little mischievous,” and was said to have enjoyed music and the company of another patient in the asylum. The original drawings are captioned “Acute Dementia” (left) and “Idiot – Salpêtrière” (right). Both drawings are unsigned.

Author: Isla Macfarlane, Intern, University of Edinburgh, MSc Book History and Material Culture.

References

Doyle, Derek. “Notable Fellows: Sir Alexander Morison (1779-1866).” Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, vol. 41, no. 4, 2011, p. 378. doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2011.420.

“monomania, n.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, 2018. www.oed.com/view/Entry/121474.

Moore, Norman. “Morison, Sir Alexander (1779-1866), alienist.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/19264. [All quotations in the above article are from this book.]

Morison, Alexander. The Physiognomy of Mental Diseases. London, 1838.

“physiognomy, n.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, 2018. www.oed.com/view/Entry/143159.

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources