Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories

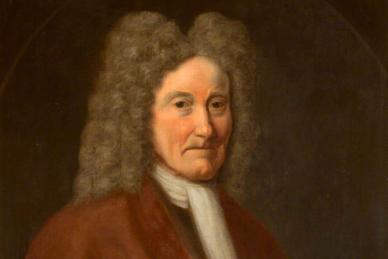

(15 April 1641–August 1722)

Founder

In 1682, Sibbald was appointed Geographer Royal for Scotland.

In 1684, Sibbald was appointed president of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

In 1685, Sibbald was appointed the first professor of medicine at the University of Edinburgh.

Throughout his life, Sibbald published numerous writings on historical, antiquarian, botanical and medical studies. His publications include:

Robert Sibbald was born on 15 April 1641 in Fife to a prosperous landed family. Sibbald’s early education at the Royal High School in Edinburgh and the Town’s College initially prepared him for a career in the church. However, his theological studies were short lived and in his memoirs Sibbald recalled that “there were then great divisions amongst the Presbyterians [that] occasioned factions in state and private families. I saw none could enter the ministry without engaging in these factions and espousing their interests. I was disposed to affect charity to all good men of any persuasion and I preferred a quiet life wherein I might not be engaged in factions of Church and State. Under this consideration I fixed upon the study of medicine.”

In March 1660, Sibbald travelled to Leiden where he learned anatomy, surgery, botany, chemistry and natural philosophy. After only eighteen months in Leiden, Sibbald travelled to Paris where he studied for nine months. Sibbald then presented himself at Angers for his examinations. After graduating, he spent three months in London with his cousin, Andrew Balfour, with whom Sibbald would later found what would become the Royal Botanic Gardens. In London, Sibbald was introduced to Robert Moray, the president of the Fellows of the Royal Society.

Sibbald returned to Scotland in October 1662 with the ambition of emulating the institutions he had encountered on the continent. As a qualified physician, Sibbald set out to improve the faculties of medicine in Scotland. Throughout his life, Sibbald concerned himself with the improvement of agriculture, mining, industry and commerce.

Sibbald’s first major project in Scotland was creating a physic garden together with Andrew Balfour. In a short period of time, Balfour and Sibbald created a garden with over 800 medicinal plants. They joined forces with James Sutherland who also had a great knowledge of plants and gardening. The garden was fully established by 1670 and received a royal warrant in 1699. Sutherland was appointed King’s Botanist in the same year. The garden continued to grow, move and expand until it moved to its current location in 1820 and opened as the Royal Botanic Gardens of Edinburgh.

After the garden had become firmly established, Sibbald set out on his next great project for Scotland; studying the natural resources and geography of Scotland. Sibbald’s cousin, Patrick Drummond, Earl of Perth, proved to be an incredibly important relationship for Sibbald. Perth, one of the King’s most influential advisors in Scotland, persuaded the king that Sibbald’s project of surveying Scotland would be beneficial in the management of Scotland’s resources and economy. Sibbald was appointed Geographer Royal and embarked on a comprehensive survey of all the natural and cultural resources of Scotland. The results were going to be published in two volumes. However, Sibbald did not receive any financial support for the enterprise and consequently the project was never complete. By 1698 it had become clear this project was not meant to be. Perth had been imprisoned following the Revolution of 1688 and Sibbald himself had suffered humiliation. Sibbald remained committed to uncovering Scotland’s natural resources and in 1698 wrote A Discourse anent the improvements that may be made in Scotland for advancing the wealth of the kingdom.

Failure did not deter Sibbald, who then set upon a course to unite Scotland’s intellectual capital. Following the examples he had seen on the continent of intellectual minds coming together, Sibbald attempted to found a Royal Society of Scotland based on the London model. His attempt was partially successful; forming what would later become the Royal Society of Edinburgh, which received its charter in 1783.

Another concept in Sibbald’s plan for improving Scotland was establishing a College of Physicians. Sibbald admired the medical colleges he had encountered on the continent and Scotland in this period did not have any medical institutions to compare. Early attempts at regulating medicine in Scotland by creating a College of Physicians had been unsuccessful. Sibbald renewed attempts to found a College and held meetings with the leading physicians in Edinburgh by 1680. This early group shared a commitment to science and medicine and discussed cases, books, philosophy and natural history. The opportunity to found a college presented itself in 1681. For the first time in almost a hundred years there was a royal court in Edinburgh and at this time Perth still had political clout with the king. Sibbald and Balfour obtained an audience with the Duke of York and presented their petition for the establishment of a College of Physicians. The proposed charter was signed and the Great Seal was appended on St. Andrew’s Day 1681.

Sibbald remained a key figure in the College and contributed greatly to the foundation of the College’s library. Sibbald became president of the College in 1684 and began planning to create a medical school within Edinburgh’s university. The death of the king in 1685 and succession of James II, a Roman Catholic, led Sibbald to convert to Catholicism, an unpopular move. Sibbald quickly recognised flaws in the Catholic priests of Edinburgh, however the damage had been done and a mob broke out, choosing Sibbald as one of its Catholic targets. Sibbald escaped to London and was made an honorary Fellow of the London College of Physicians. In September 1686 Sibbald returned to Edinburgh and rejoined the protestant church, but the damage had been done and the Fellows of the College no longer trusted him. The College divided into factions fraught with internal differences stemming from religious bigotry and political rivalry.

Sibbald continued, as aforementioned, on other projects and continued to play a role in the College. Sibbald and Balfour had drafted early versions of the Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia and by the 1690s efforts were renewed to finalize the Pharmacopoeia. The College’s most long-lasting dispute was over the new pharmacopeia, with Sibbald and Balfour in one camp and the “new science” in the other.

In the early eighteenth century, Sibbald continued to play advocate for the faculty of medicine at Edinburgh University. In 1706, Sibbald, now 65 years old, was still denied the right to teach medicine at the university and so he attempted to teach medicine on his own. An ad in the Edinburgh Courant appeared on 24 February 1706 offering private tutorship in natural history and medicine. Whether any students answered Sibbald’s ad is unknown, though it is known his scheme was abandoned. He also spent the early years of the eighteenth century writing a number of works on geographical and statistical data

Sibbald was married twice and had two surviving daughters. By 1707-8 he faced severe financial difficulties and was forced to sell a large portion of his library. Sibbald died in 1722 having contributed much to the medical profession and intellectual life of Edinburgh. He is buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard.

Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories