Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

Dermatology has a relatively short history. Although the first medical text specifically written on the skin dates from the 1500s it was only in the late 1700s that it began to be viewed as a specialised branch of study. The microscope was a key tool in the developing study of the complex and layered structure of the skin.

Visualising technology was central to the establishment of this new specialty. Advances in printing, modelling and finally photography allowed physicians and surgeons to capture and share the minute differences between skin complaints. This aided in the creation of classifications – to create a common language of names for individual diseases of the skin.

By the Victorian period dermatological texts, often more highly illustrated than other medical texts, were produced in large numbers and purchased not only by medical practitioners, but by the lay public also. This did much to popularise the idea of consulting a dermatological specialist. The skin was no longer to be blistered or cut, it was a boundary which was important to keep healthy and unbroken.

New and often conflicting ways of classifying and understanding skin diseases were developed by physicians in the 1800s. Developing a common language which crossed national boundaries was essential to sharing information, diagnoses and methods of treatment.

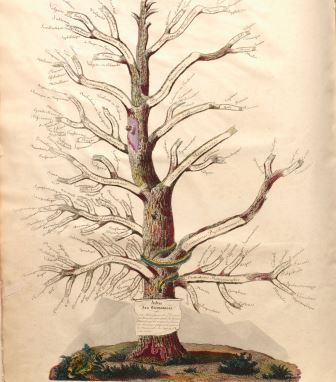

Alibert was the chief medical officer at the Saint Louis hospital in Paris and was the first to develop a teaching centre focused around diseases of the skin. In England new classifications of skin diseases were based on their outward appearance. Alibert’s system, shown here in his ‘Tree of Dermatosis’, was much more complicated. Based on botanical classification, he arranged skin diseases into families, genera and species. Alibert arranged them not only by their appearance, but by their symptoms, causes and duration. His tree was not accepted by his peers and Alibert and his research became the subject of ridicule and attacks.

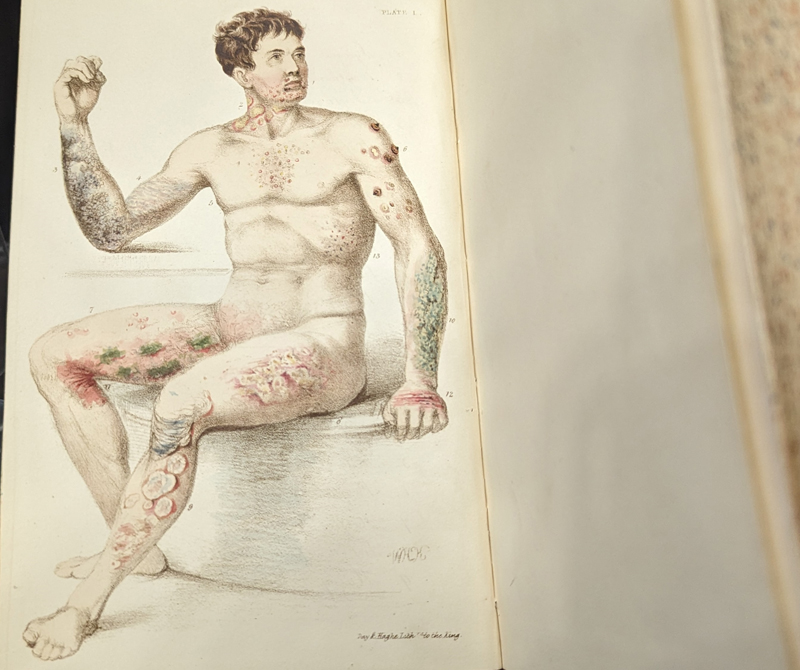

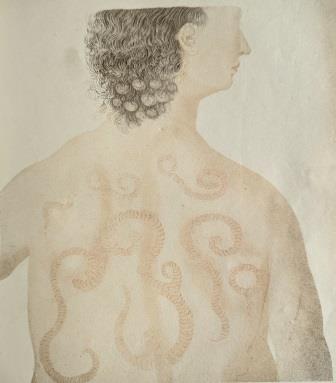

This text, written by English surgeon Jonathan Green, depicts a man with 13 different skin diseases on his torso and back. This illustrative style is based on the medieval ‘wound man’ image, a popular method of depicting wounds or other ailments which acted as a contents table of sorts, demonstrating all the diseases discussed within the following text on a single body.

Green used this publication not only to share his insights into skin diseases but also as a method of promoting his budding new enterprise – a suite of fumigating baths. Green wasn’t the first to suggest that bathing could be an effective treatment for skin complaints but he may have been the most committed, taking out a patent on a portable vapour bath and touring Europe to study the use of medicinal baths across the continent.

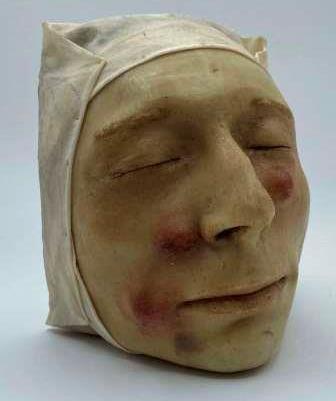

It is often difficult to tell whether a wax model was cast from the face of a living or dead person. Anatomical models and death masks have been produced since antiquity, often using clay, marble or ivory. Wax models, or moulages, for medical teaching and study were developed in the 1600s in Italy.

While such models were used in surgery, obstetrics and ophthalmology, it was in the field of dermatology that they reached their apex.

The growth in identified skin diseases in the 1700s and 1800s meant it was increasingly important to be able to distinguish minute differences between them.

As a result a distinct field of art developed and some artists, or moulagers, dedicated their careers to molding and colouring models of rashes, tumours, scars and pimples.

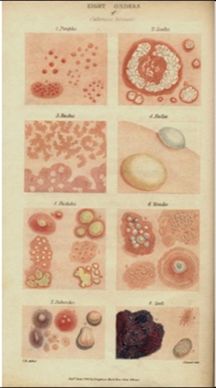

This illustration shows Bateman and Willan’s eight classifications of skin disease. Classes were based on

the external characteristics of lesions.

Thomas Bateman was student, colleague and later successor to Robert Willan. Often regarded as the founding figure of modern dermatology, Willan defined the first four classifications of skin diseases in volume one of his seminal work, On cutaneous diseases, in 1808. Willan died in 1812, before he could publish his second volume.

Devoted to his friend and the study of dermatology, Bateman finished Willan’s work and published this volume in 1819. Together, Bateman and Willan’s work was the first modern attempt to classify and properly define skin diseases in Britain and was influential at home and abroad.

This illustration depicts a woman suffering from psoriasis gyrata, a rare variation of psoriasis which caused spiralling eruptions on the skin.

Dermatological illustrations in the 1800s were often stylised or romanticised versions of skin diseases. The skin markings are often reminiscent of flora, tentacles or tapestries. The folds of fabric or the details of lace bonnets were often captured in as much detail as the intricacies of the diseased skin itself.

The patients shown in these illustrations were commonly pauper patients at charitable London hospitals and yet they were often depicted in print in poses reminiscent of aristocrats or concubines of the classical period.

The world’s first museum of dermatological wax moulages opened at the Saint Louis hospital in Paris in 1867. This museum employed internationally renowned moulage makers and thousands of detailed wax models were created and displayed there.

Around 1900 the Edinburgh physician and dermatologist Robert Cranston Low visited the Paris museum to study their remarkable exhibits. Low brought back to Edinburgh details of the secret techniques used by these expert French moulagers. He then shared these details with Miss Rae who worked as a secretary at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.

This moulage, and many others like it, were moulded by Rae based on patient cases at the Edinburgh Infirmary. This model is of a Mrs Fisher who suffered from Boeck’s sarcoid, now commonly known as sarcoidosis, a disease which causes small patches of swollen tissue to develop in the organs.

This blog was developed to accompany the exhibition Skin: A Layered History, which ran from 10 February 2023 to 13 October 2023.

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources