Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

Most of the portraits we hold include specific objects and visual references that relate to the careers of the medical practitioners (and other scientific professionals) that they depict. Many of the accoutrements used in this kind of professional portrait share common traits and themes, which remained consistent over much of the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries.

The most common and recurring props used in this type of portraiture included books, papers, and writing implements. The use of these props fed into a central trope depicting the medical man as learned. Popular compositions represented the sitter in a domestic context, often a library, surrounded by books either seated in an armchair or stood next to a writing desk. The desire for medical practitioners to be characterised in an intellectual light can be seen in the context of the enlightenment and the principle that knowledge was at the forefront of progress.

Some portraits, although not all, used objects to make specific reference to the careers of the men depicted or to particular achievements and specialisms. In this way, prints were often used as a way to celebrate or create a public reputation for the sitter within their lifetime or posthumously.

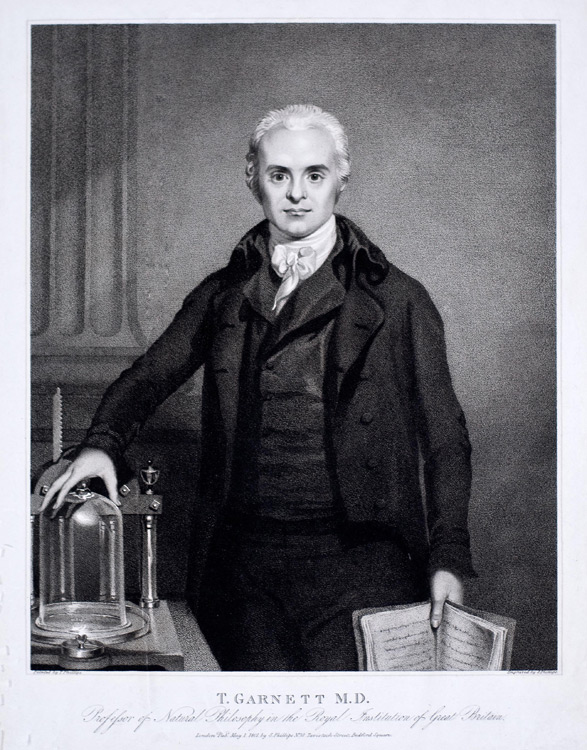

Thomas Garnett (1766-1802) was a physician and chemist born in Westmorland. He studied at the University of Edinburgh and obtained his MD in 1788. Here he was influenced by the lectures of the chemist Joseph Black and the doctrine of John Brown. During his time in Edinburgh he was active in the Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh and was president to both the Royal Physical Society and the Natural History Society.

Some late eighteenth and early nineteenth century prints in the collection occasionally break away from the standard image of the medical man as an intellectual, instead highlighting the practical side of the profession by featuring technological medical apparatus (here Garnett rests his hand on a bell jar). As the period moved forward, technology came to stand for an ideal of a teleological progress towards modernisation and advancement in scientific and medical fields. Technical equipment similar to that in the portrait of Garnett is more prominent in later prints.

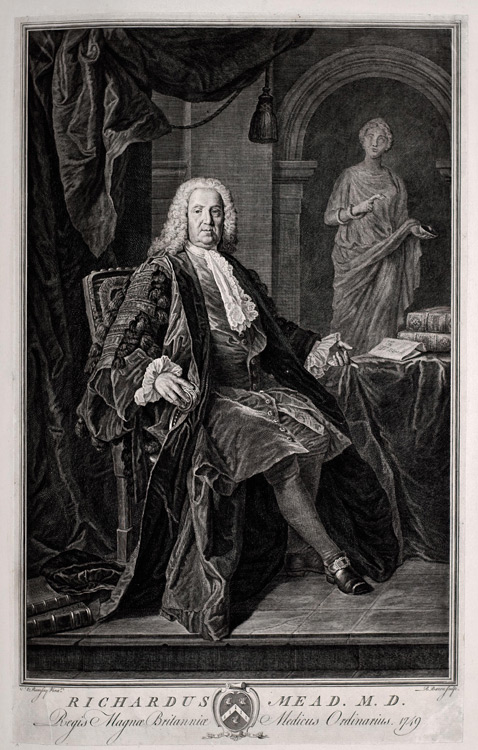

Richard Mead (1673-1754) was a physician and collector of books and art born in Middlesex. He studied at the University of Leiden, although he did not graduate. Mead embarked on a Grand Tour of Europe in 1703, where he developed an interest in antiquities. In 1703, Mead was elected to the Royal Society and physician to St Thomas's Hospital in Southwark. In 1716 he was electedas a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians.

Although Mead had a particular interest in antiquity developed on his Grand Tour of Europe, classical allusions were popular in many portraits of the long eighteenth century. Behind Mead, in an enclave surrounded by a neo-classical arch, stands a statue of the Goddess of Health, Hygeia. The drapes are also a common feature in portraiture reminiscent of the draping of a toga, additionally large expanses of cloth were expensive in this period, giving the portrait a sense of grandeur.

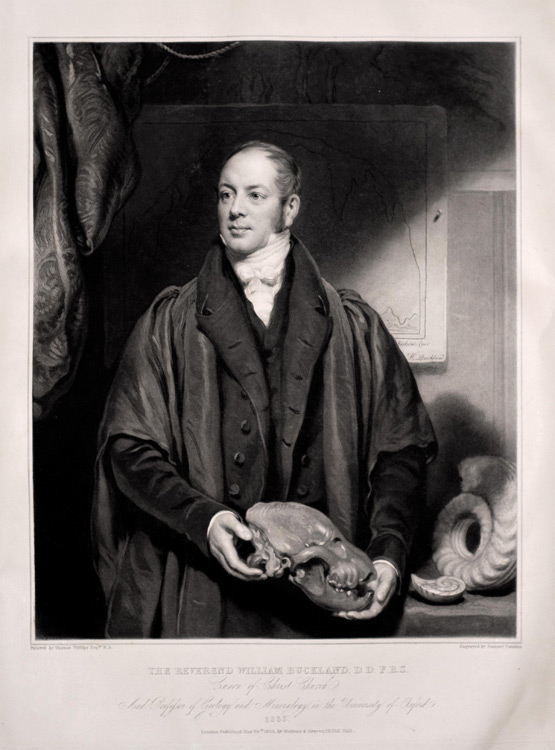

The Reverend William Buckland (1784-1856) was a geologist and Dean of Westminster, born in Devon. He studied at Corpus Christi College, Oxford from 1801 and was made a fellow of the college by 1808. He delivered lectures in geology and mineralogy in the old Ashmolean Museum, which for many years were some of the most popular in the university. Buckland was most widely famed for his hypotheses on fossil cave faunas, notably in Kirkdale Cavern, Yorkshire.

This likeness alludes specifically to Buckland’s acclaimed achievements in the field of geology. He is portrayed in his academic robes surrounded by fossils and holding an animal skull. It is perhaps unsurprising that he has been depicted in this way as it is suggested in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography that he was rarely seen without his academic gown and a blue bag full of his most recently discovered fossils and bones ready to demonstrate.

William Harvey (1578-1657) was a physician born in Kent. He studied at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. In 1609 Harvey became physician to St Bartholomew's Hospital. In 1639 Charles I made Harvey physician-in-ordinary. As such Harvey accompanied the King to Scotland on several occasions. In 1604, Harvey was admitted to the Royal College of Physicians in London, where an annual oration is held in commemoration of him. His most acclaimed achievement was his discovery of the circulation of the blood.

Many of the accoutrements used in the prints were used to embellish the frame instead of as props displayed within the image. Familiar images of books and medical diagrams were used here to illustrate Harvey’s career, in particular the image of the circulatory system to the sitter’s right. Other objects were used to symbolise Harvey as a man of medicine, including the staff of Asclepius, an ancient symbol associated with medicine, healing, and the Greek God of medicine Asclepius. This is an interesting symbol to find in Harvey’s portrait as it reasserts a continuity with older traditions of medical theory based on the ideas of those including Galen and Aristotle, which Harvey’s discoveries were criticised for challenging and undermining.

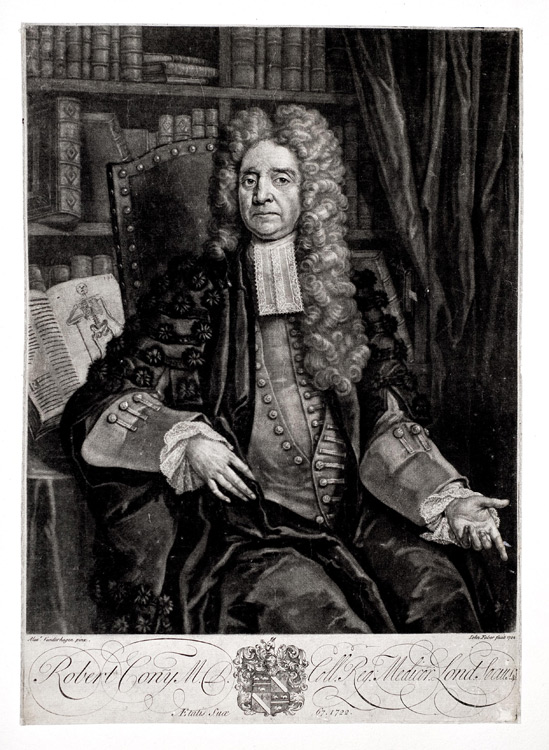

Robert Conny (c.1645-1713) was the son of John Conny, a surgeon and mayor of Rochester. Robert Conny was a physician educated at Magdalene College, Oxford. In 1693 he became a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians. He is said to have been a successful physician and on his death in 1713 a monument was erected in Rochester Cathedral in his memory.

This print made in 1722 is an illustrative example of the trend to portray medical practitioners in a scholarly way. He is seated in an armchair in front of a full and well-used bookshelf. Behind him to his right is an open book with both text and a scientific diagram of a skeleton, implying he is part way through his study.

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources