Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

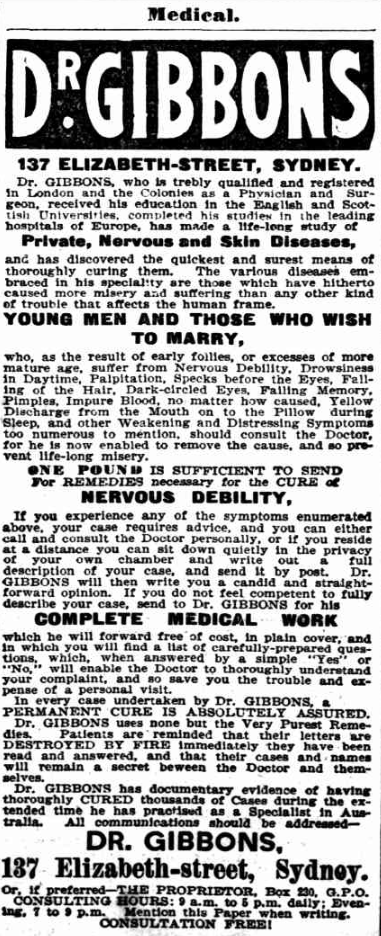

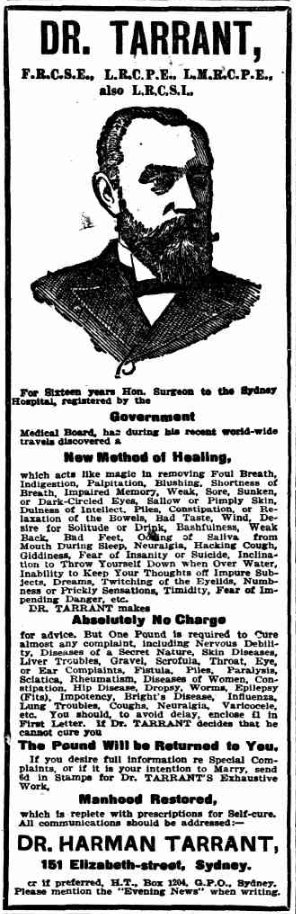

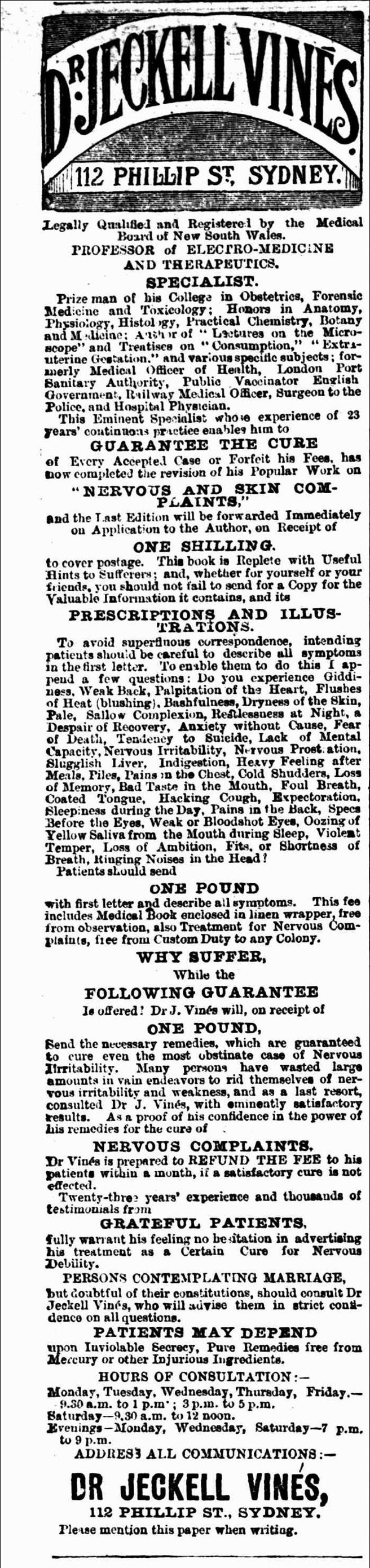

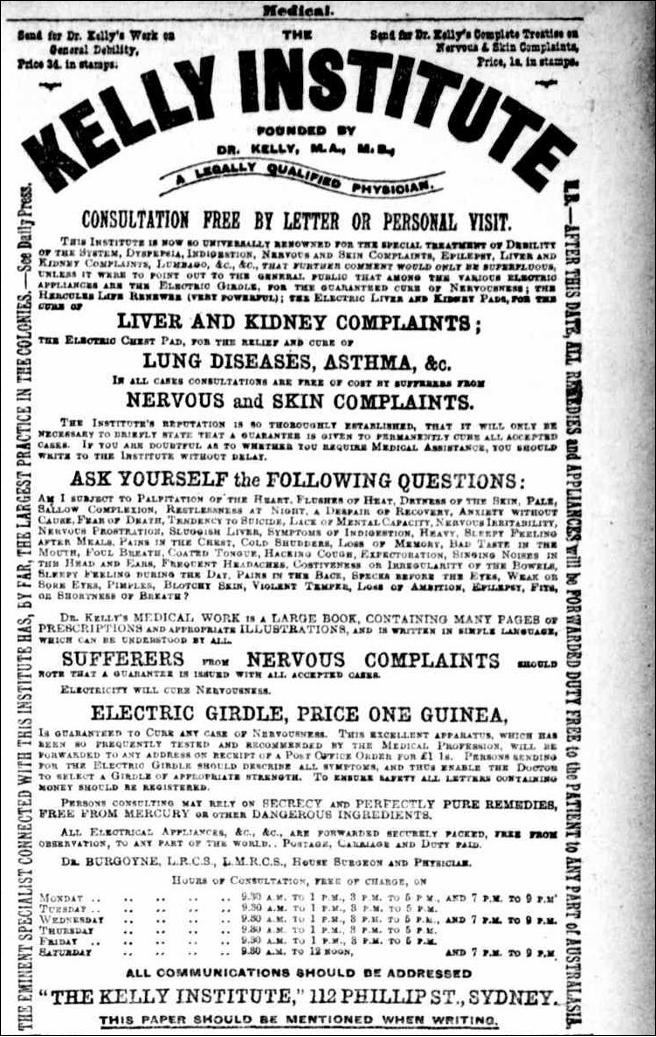

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the College’s Council heard a number of disciplinary cases regarding doctors accused of “unbecoming and unprofessional” behaviour by advertising their services in Australian newspapers. At first glance this seems a rather minor offence considering the punishment was expulsion from the College potentially being struck off the medical register. However a closer look at some of the adverts reveals they were less about doctors trying to encourage more patients, and more about quackery, with references to secret cures known only to the doctor or miracle treatments such as the “electric girdle”.

Being so far removed from the majority of the College’s membership, the Council relied on networks of professional organisations to identify wrongdoing. In the College’s archives, there are several telegrams sent to the secretary by the Queensland branch of the British Medical Association, identifying bad behaviour from people associated with the College. Interestingly, a recurring theme in these telegrams is the idea that the advertisements had been a common problem in New South Wales, where most of these practitioners were based, and it was only when the transgressions had crossed state lines by advertising in Queensland based publications that they felt the need to act. This does however raise the question of what the New South Wales branch thought of these advertising trends? A mystery that may be solved by an article reporting the election of one Dr Armitage Forbes, who we will return to later, to the branch’s board in 1881.

The responses of these doctors to the disciplinary processes were quite varied, ranging from apologetic to brazen.

Charles Gibbons, claimed not to have realised that placing adverts in the paper was against the college’s by-laws, having lost all his books in a house fire. He said that he had been in contact with another licentiate of the College, Harman Tarrant, who had informed him that there was nothing wrong with the practice, and indeed in the more commercially minded land of Australia, it was necessary for a doctor to advertise to gain business. Coincidentally enough, the next case in the catalogue is concerned with a certain Harman Tarrant, with very similar results.

Henry Jeckell Vinés, who had been a Fellow of the College, argued that the adverts had not been placed by him. He claimed that having exhausted his funds and health in emigrating to Australia, he responded to an job advert for a two year role as locum tenens for a Dr Kelly in Sydney. Jumping at the opportunity he made his way to Sydney, only to discover that rather than a traditional practice, he had taken on a role as a correspondence doctor. Worse, he was now locked into a rather unscrupulous binding contract he had signed without reading.

The aforesaid Dr Kelly had taken out adverts using Vinés’ name before he even arrived in Sydney, having previously done the same using his own name, as well as another doctor prior to Vinés. Like Gibbons, he begs forgiveness from the college, though amusingly Vinés shares an example of a recent publication of his, and asks the college to compare it to the grammatically flawed advert as evidence of his innocence. He also included a medical note advising that Henry Jeckell Vinés would be unable to appeal his case in person, as his chronic asthma and emphysema meant that a trip to Edinburgh in autumn would put his life at risk. This note was signed by his physician, one Dr Edward Prince Vinés.

While the truth of Vinés’ claim to have stumbled into his new role is lost to history, a look through the Australian newspapers for the time does back up his story. We can see an advert for Dr Jeckell Vinés based in 112 Phillip St. Sydney in 1895. Looking back to 1892, another advert reveals that this same address is home to The Kelly Institute, founded by Dr Kelly, identified only as “a legally qualified physician”. The House Surgeon and Physician for the Institute is a Dr Burgoyne LRCS LMRCS, presumably the other doctor that Vinés mentions.

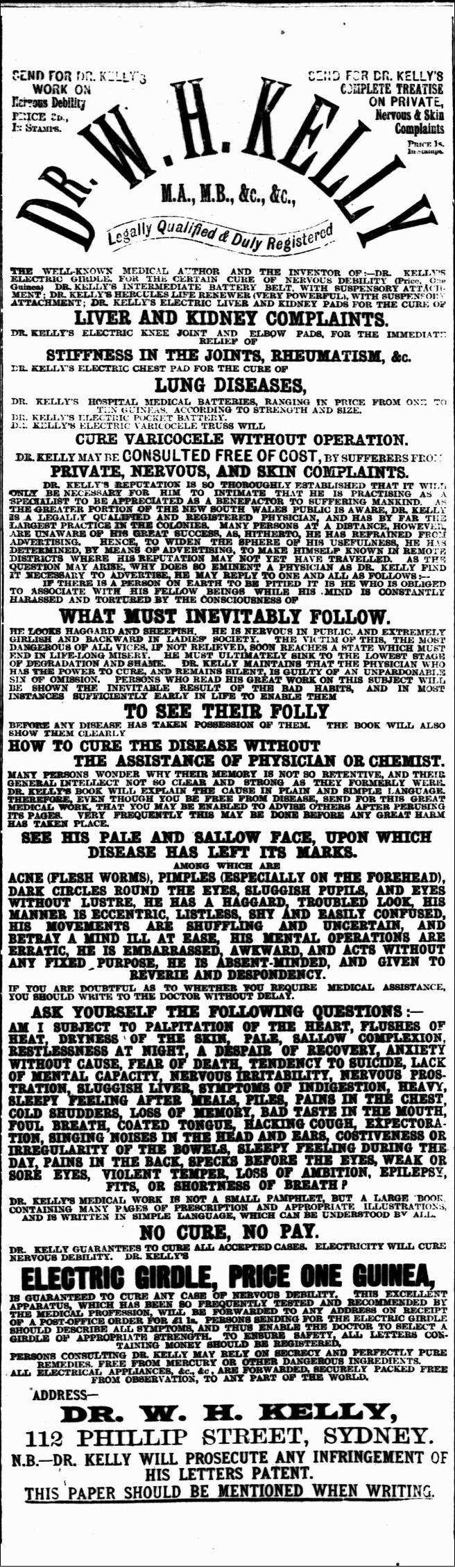

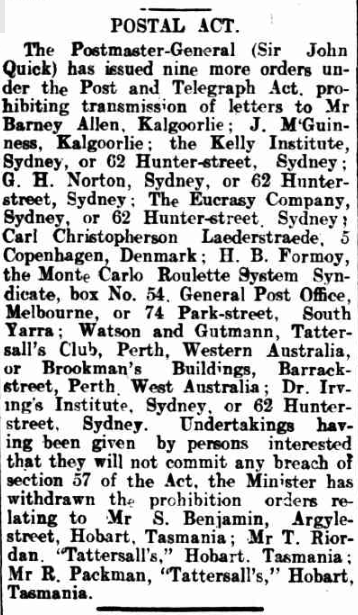

Even further back to 1891, we find Dr W. H. Kelly, “the well-known medical author and inventor” of the eponymous Electric Girdle, Intermediate Battery Belt, and Hercules Life Renewer, among many other electrical gadgets. It’s not hard to see why the College would view Vinés’ association with Dr Kelly as disreputable, and by 1909, even the Postmaster-General would agree, issuing a Postal Prohibition for the Kelly Institute’s new premises.

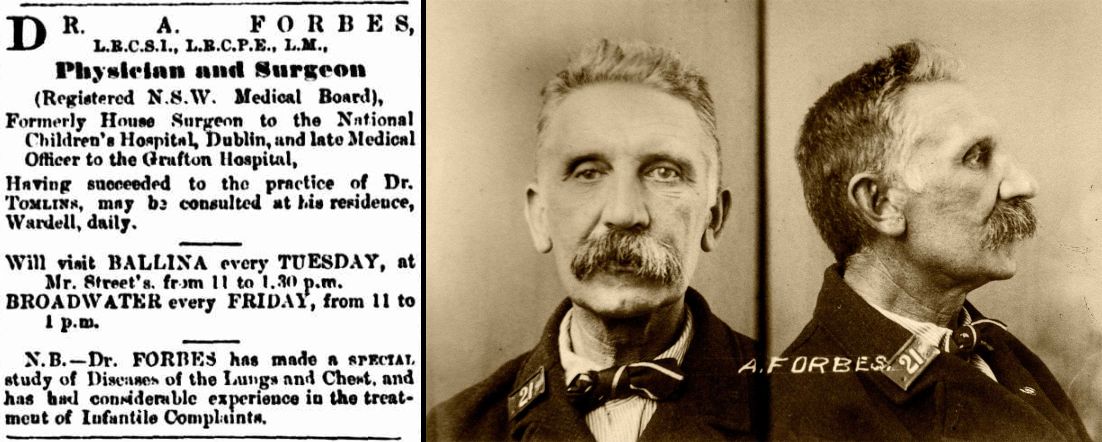

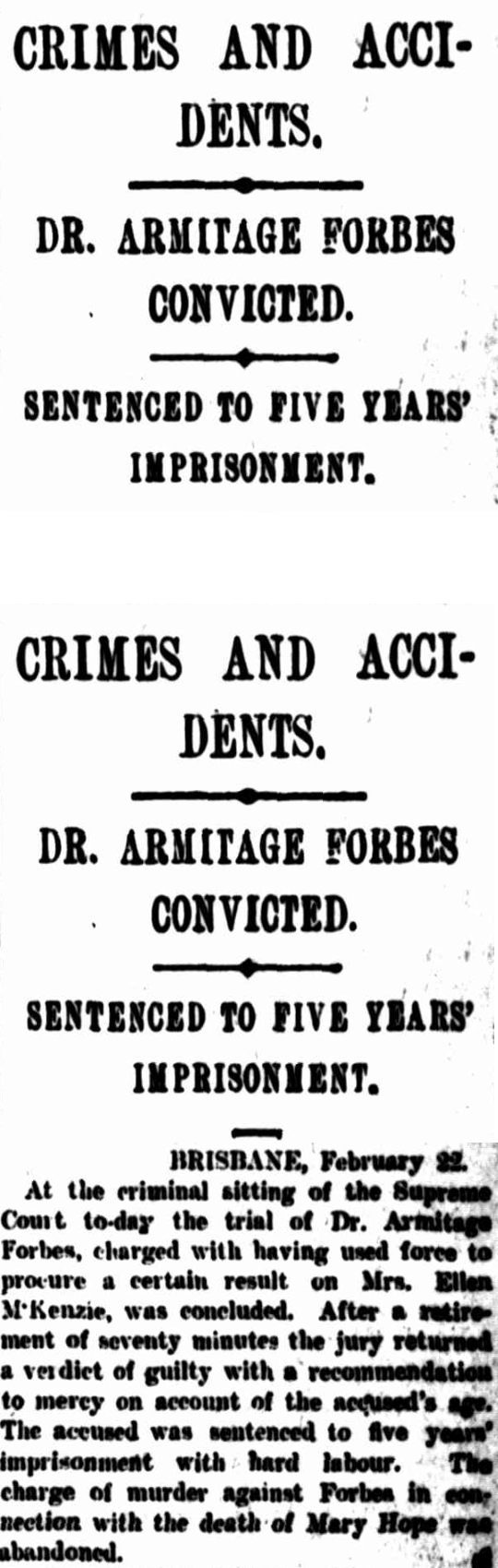

There is a stark contrast however with the previously mentioned Dr Armitage Forbes. While his adverts appear reasonably innocuous, and he is initially apologetic for his actions, like Gibbons and Tarrant, Forbes argued that advertising and mail-order healthcare were absolutely necessary in Australia, due to the size, low population density and under-developed infrastructure. Whatever the merit of these arguments, the College was unconvinced, and when Forbes took out further advertisements in newspapers, stripped him of his licentiate, thereby striking him from the General Register.

In response Forbes wrote an angry letter to the College, in which he expressed regret at ever apologising for his initial adverts, and claimed that no longer being bound by the College’s rules meant he would be able to reach his full potential as a doctor. It is unclear exactly what Forbes had in mind, however his story ends rather tragically. Three years later, in a highly publicised case, he was charged with murdering a pregnant patient. The following year Forbes was convicted of “unlawfully using force” to cause an abortion, and was sentenced to five years hard labour.

After his release, Forbes disappeared from his cabin on board a steam ship off the coast of northern Australia. Following a brief inquest, he was declared dead after his widow asserted he fell from the porthole following a mini-stroke, to which he had become prone after his sentence.

It is all but impossible now to know for certain what truly prompted these men to act in the way they did, but their actions and the College’s responses do highlight the challenges faced by the College during the colonial era. A body set up for national purposes was now stretched across the globe, with members working in cultural and geographical circumstances unfamiliar to the majority of their compatriots.

The disciplinary cases held in the College’s archives can provide an insight for anyone interested in both these challenges and the history of Quackery more generally, not just from Australia, but also from college members in India, South Africa and even the UK itself.

Author: Cat Goodrick

Image Sources

"Advertising" Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 - 1931) 27 October 1898: 8. Web. 26 Jun 2023 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article114045251>.

"Advertising" Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 - 1931) 7 October 1899: 8. Web. 26 Jun 2023 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article113688131>.

Advertising (1894, December 8). Weekly Times (Melbourne, Vic. : 1869 - 1954), p. 28. Retrieved June 26, 2023, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article221163725

"Advertising" Referee (Sydney, NSW : 1886 - 1939) 30 November 1892: 7 (Edition 2). Web. 26 Jun 2023 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article120653859>.

"Advertising" The Northern Mining Register (Charters Towers, Qld. : 1891 - 1892) 16 December 1891: 9. Web. 26 Jun 2023 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article79315431>.

"POSTAL ACT." Daily Telegraph (Launceston, Tas. : 1883 - 1928) 16 August 1909: 5. Web. 26 Jun 2023 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article152032571>.

"Advertising" The Richmond River Herald and Northern Districts Advertiser (NSW : 1886 - 1942) 24 December 1891: 2. Web. 26 Jun 2023 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article127718614>.

"CRIMES AND ACCIDENTS." Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Qld. : 1878 - 1954) 23 February 1905: 5. Web. 26 Jun 2023 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article53034103>.

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources