Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

Exposed skin was a site of suspicion for any cutaneous change. Alongside other disfiguring maladies, the plague manifested on the skin and was a significant anxiety for many. Therefore, citizens were highly suspicious of their own and others’ skin. The prevalence of lesions, carbuncles, rashes and buboes presented multiple recognisable symptoms. The face was particularly scrutinised for change. Believed to be caused by imbalanced humours, early modern men and women ‘read’ the colour, location and size of swellings and boils on their skin. Disorders presenting on the skin were often categorised between larger swellings in specific places on the body or smaller bumps, stripes and colour changes of the entire body.

Concerns about facial scarring were prevalent in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries because of intense facial exposure. A multitude of deadly diseases marked the face during this period. The devastation of bubonic plague, smallpox and French pox resulted in increased anxiety to protect the exposed skin of the face. As one advertisement proclaimed in 1702, the surgeon Mr Nedham was ‘daily successful in … taking away all sores, scabs and pains’, suggesting that medical practitioners utilised popular anxieties about facial marks and scarring to increase their profits. Facial scars and blemishes were often covered by black patches.

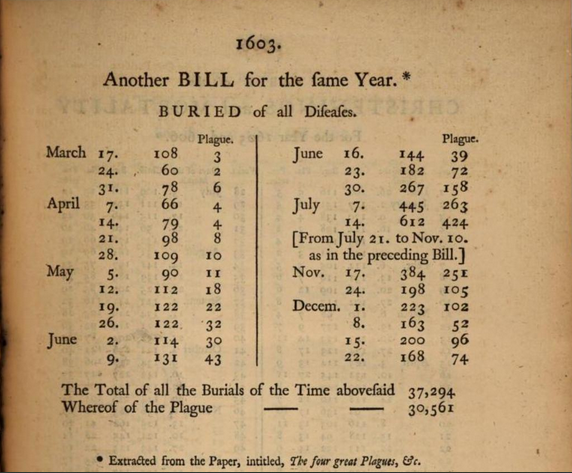

The high death rates from the plague were regularly published in a printed broadside called the London Bills of Mortality, wherein the readers were given a local breakdown of the death toll. Out of a total of 37,294 deaths, 30,561 were due to the plague in 1603 alone.

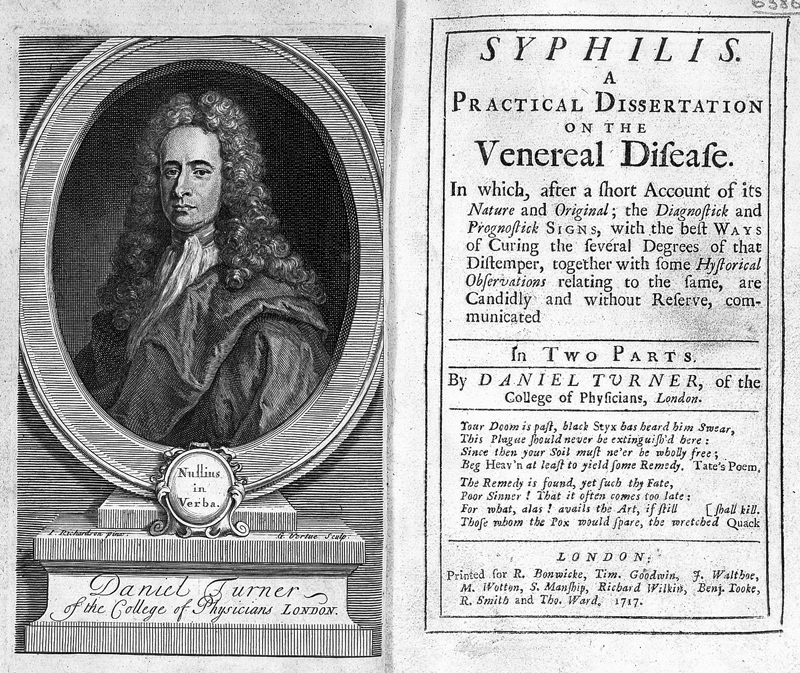

London-born physician and surgeon Daniel Turner suggested in his text De Morbis Cutaneis (1736) that diseases manifested on the skin because of its unavoidable contact with poisonous vapours in the air. Diseases like the plague were imagined as infiltrating the skin through the pores, eating away at the vulnerable and soft tissue. According to Turner, the plague was a ‘highly corrosive Acid’ on the skin, destroying the little protection it offered to the bodily interior. Eating away at the skin, plague parted the boundary between exterior and interior. The interior was always vulnerable because of the body’s holes which functioned as points of both entry and exit.

One of the most prominent diseases of the early modern period was the French pox, perhaps more recognisably known today as syphilis. Signs of the pox appeared on the skin in a wide array of lesions, ulcers and pustules, most notably on the genitals. The pox destroyed the body’s boundary, destabilising the exterior and interior divide. As an advertisement in 1725 in Mist’s Weekly Journal highlights, surgeons aimed to cure ‘ulcers in the throat, lost palate, sinking in the nose’ as well as ‘ulcers and pocky warts’. The skin, already occupying an ambivalent position, became precarious as the face seemed to disintegrate. As a practising surgeon Charles Peter recorded in his 1686 tract Observations of Venereal Disease:

“Some have the uvula and the palat of the Mouth eaten away by Ulcers, and many you see who loose their Noses by this violent Disease, some have the tip of the Nose and Nostrils eaten away, some loose their Eyes and many their hearing, and some of their mouths drawn away.”

The disease was described as ‘eating’ away the skin. It was imagined as an insidious outbreak of pollution. The other sites of suppuration Peter noted are also openings to the body’s interior. Later stages of the pox covered prominent and visible areas of the skin with boils, spots and oozing ulcers.

Highly contagious and acute, smallpox is believed to have existed for over 3000 years and during that time caused millions of deaths. Similar to plague and French pox, smallpox is spread through close contact. Turner suggested in De Morbis Cutaneis that diseases manifested on the skin because of its unavoidable contact with poisonous vapours in the air accessing the body through the pores. He wrote that:

“I conceive therefore that the Alteration made in the Skin by the Small-Pox, at whatever Age it comes, is the true Reason why that Distemper never comes again: For the Distention which the Glands and Pores of the Skin suffer at that Time is so great, that they scarce ever recover their Tone again.”

Turner suggested that the pores and glands of the skin expand outwards in a ‘distention’ that cannot be reversed. The barrier that the skin represented is transgressed and then destroyed by the disease. Turner posited that people only suffer from smallpox once because the disease alters the skin so drastically. The skin was perceived and understood to stretch, contract and rupture. As Turner indicated, smallpox scarring was disruptive because it damaged the skin’s glands and pores. The skin, especially the skin of the face, was a liminal zone that required control and protection from disease entering through the pores and causing scarring. The skin was fragile because it ‘suffer[ed]’. Occupying a distinct aesthetic consideration, the skin’s ability to ‘distend’ indicated its flux. That the pores ‘scarce ever recover their tone again’ highlights the inflexibility of the skin. Despite its inherent permeability, Turner here represented the manifestation of smallpox as forcing matter outwards to create the ‘ulcerous pustules’ which often scarred the skin permanently.

Much of the early modern period was concerned with various harmful and deadly diseases, most notably plague and pox. This widespread contagion emphasised the vulnerability and the danger of the body. The pervasiveness of disfiguring disease in this period transformed perceptions of the skin into a layer to be continuously controlled. The desire to monitor our and other’s skin hasn’t altered in six hundred years and is unlikely to change just yet.

References

Thomas Birch, A collection of the yearly Bills of Mortality, from 1657 to 1758 inclusive (London: 1759)

Daniel Turner, De morbis cutaneis. A treatise of diseases incident to the skin. In two parts. With a short appendix concerning the Efficacy of Local Remedies, and the Manner of their Operations. By Daniel Turner, of the College of Physicians, London (London: Printed for R. Wilkin, J. and J. Bonwicke, S. Birt, T. Ward and E. Wicksteed, 1736, 5th edition)

Mist’s Weekly Journal (31 July 1725) from Rictor Norton, Early Eighteenth-Century Newspaper Reports: A Sourcebook, ‘Cures for Venereal Disease’

The English Post (2-5 January 1702) from Rictor Norton, Early Eighteenth Century Newspaper Reports: A Sourcebook, ‘Cures for Venereal Disease’

Samuel K Cohn Jr, Cultures of Plague: Medical Thinking at the End of the Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 50-72

Emily Cockayne, Hubbub: Filth, Noise and Stench in England, 1600-1770 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007)

Olivia Weisser, ‘Roy Porter Student Prize Essay: Boils, Pushes and Wheals: Reading Bumps on the Body in Early Modern England’, Social History of Medicine, 22.2 (2009), 321-39 <https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/hkp011>

Barbara Duden, The Woman Beneath the Skin: A Doctor’s Patients in Eighteenth-Century Germany, trans. by Thomas Dunlap (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997)

Jon Arrizabalaga, John Henderson and Roger French, The Great Pox: The French Disease in Renaissance Europe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997)

Naomi Baker, Plain Ugly: The Unattractive Body in Early Modern Culture (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010)

Lucinda McCray Beier, Sufferers and Healers: The Experience of Illness in Seventeenth-Century England (London: Routledge, 1987)

Author: Stephanie Bennett

This blog was developed to accompany the exhibition Skin: A Layered History, which ran from 10 February 2023 to 13 October 2023.

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories