Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

Traditionally canes and physicians have had a close association. In Greek mythology the deity Asclepius, who was associated with medicine and health, wielded a rod with a serpent wound round it and many modern versions have continued this symbolism.

The physicians’ cane came into vogue in Britain in the eighteenth century via France, and it came to be associated with the professions, a means of emphasising intellectual rationality over physical prowess.

Satire played a significant role in uniting the cane with the identity of the physician; but this was rarely a flattering depiction. Drawing on contemporary discussions related to the ‘effeminate’ and ‘immodest’ nature of eighteenth century masculine dress, satire sought to ridicule the ‘fashionable’ and thus foolish physician. Like the nineteenth century policeman and his truncheon, the physician’s belief in the authoritative nature of his cane became a famous parody, and the two were closely associated.

Sketch by Kay of physician Andrew Duncan

Judgements varied in their tone. The satirical prints of John Kay, a native to Edinburgh, were ‘gently mocking’. A friend of several notable members of the Scottish gentry, Kay’s satires were mocking of eighteenth century society as a whole, and not specifically one social or professional grouping.

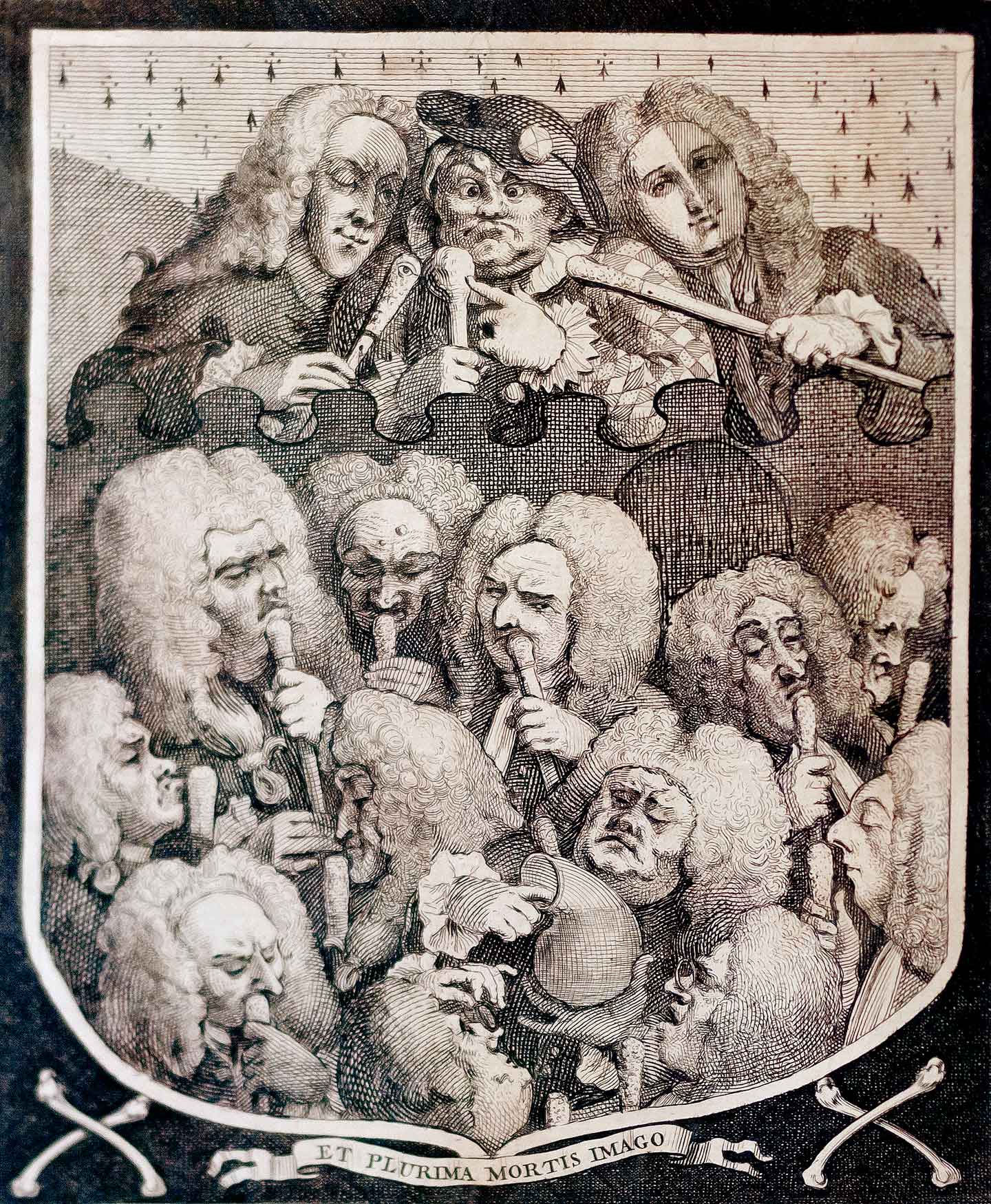

Hogarth, by contrast, was more vehement in his criticisms of society. His satire, ‘The Arms of the Honourable Company of Undertakers’, was far more targeted in its ridicule.

William Hogarth, 'A Consultation of Physicians', 1736

The individuals in the image are known doctors and quacks of the period, sniffing their canes and examining a urinal flask. The image is framed in a satirical coat-of-arms with the motto, ‘Et Plurima mortis imago’- ‘And many an image of death’. Hogarth’s portrayal therefore is specifically critical of the medical profession, and not just the foolishness of men of heightened social status generally.

Largely hand crafted in France, these canes featured in a wider context of a growing delight in European aristocratic fashionable tastes.

Yet despite such elegant connotations, the cane also spoke of masculinity. An accessory only ever adorning men, it replaced the sword as a symbol of manhood (later to be replaced with the umbrella, see Mr Punch among the Doctors). In contrast to the sword, no suggestions were made of bravery or military prowess, instead the cane was associated with the professions and intellectual rationality.

However, from the 1760s the appeal of European elegance began to decline. Although in part a result of the souring of Anglo-French relations, it was more related to contemporary discourse that raised suggestions of 'effeminacy' and 'pomposity'. The creation of the English ‘Macaroni’ only reinforced such fears. Increasingly deemed contrary to the English temperament, the symbolic nature of the cane was also implicitly challenged. The satires of both Kay and Hogarth exemplify this. However, a reluctance to entirely erase the cane from the physician’s identity led to its inclusion in the College regalia and in many photographs and portrait paintings, well into the twentieth century.

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories