Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

This blog was developed to accompany the exhibition Wild & Tame: Animals in History which runs from 19 July 2024 to 9 May 2025.

Animals appear everywhere in human societies, both in a physical sense and as cultural metaphors and myths. When the first animals were domesticated, they stopped being just the predators we feared and the prey we chased – they became constant companions who changed the course of human history. The taming of wild animals occurred slowly, over thousands of years in different parts of the world.

It was one of the most important turning points in human history that triggered a shift from a migratory lifestyle to settled living. Animals had their place in every human culture. They became the first symbolic objects – humans drew them in caves long before the first animal was domesticated and our fascination with them continues. The way we viewed them and interacted with them changed through history, but animals remain an integral part of the lives of people across the world.

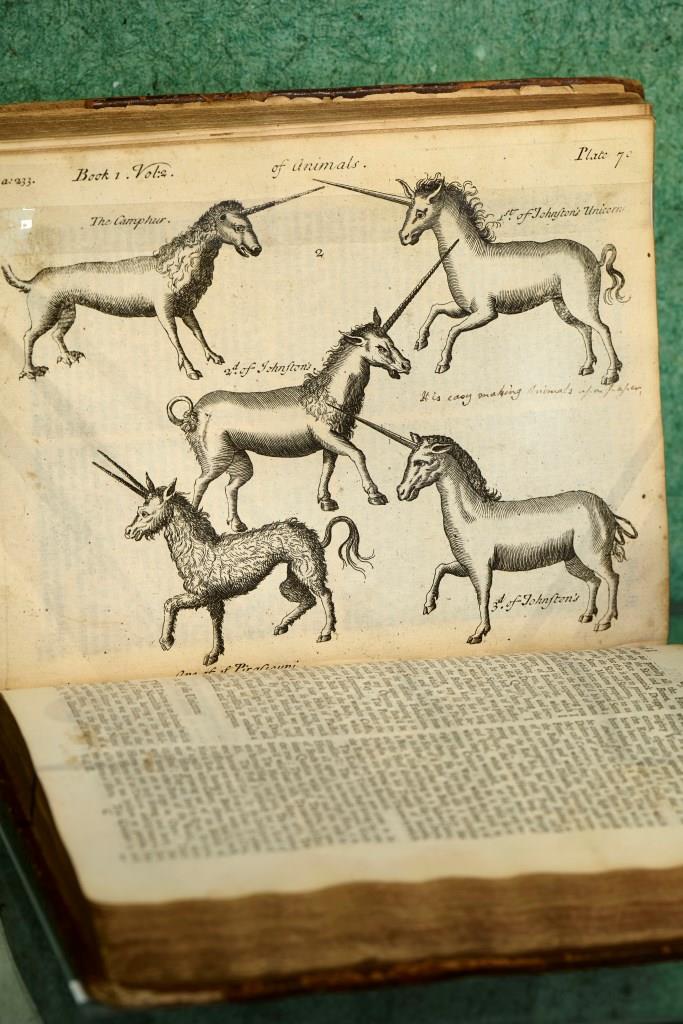

The unicorn is the most archetypal mythical animal. Unicorn descriptions first appeared in the Babylonian and the Indus civilizations and were probably depictions of the Indian rhinoceros. In ancient texts the unicorn is wild, quick and impossible to capture. Over time, it became a symbol of protection and magical healing powers. The unicorn was a popular feature in European medieval family crests because it was believed its powdered horn could cure poisoning. Unicorns are still listed in this book of drugs made from animal parts, first published in 1694.

In Celtic mythology the unicorn is the symbol of purity, innocence and power. It was included in the royal arms of Scotland by King James I and was adopted as the national animal of Scotland. Unicorns appear on many Scottish historic buildings, monuments and coins.

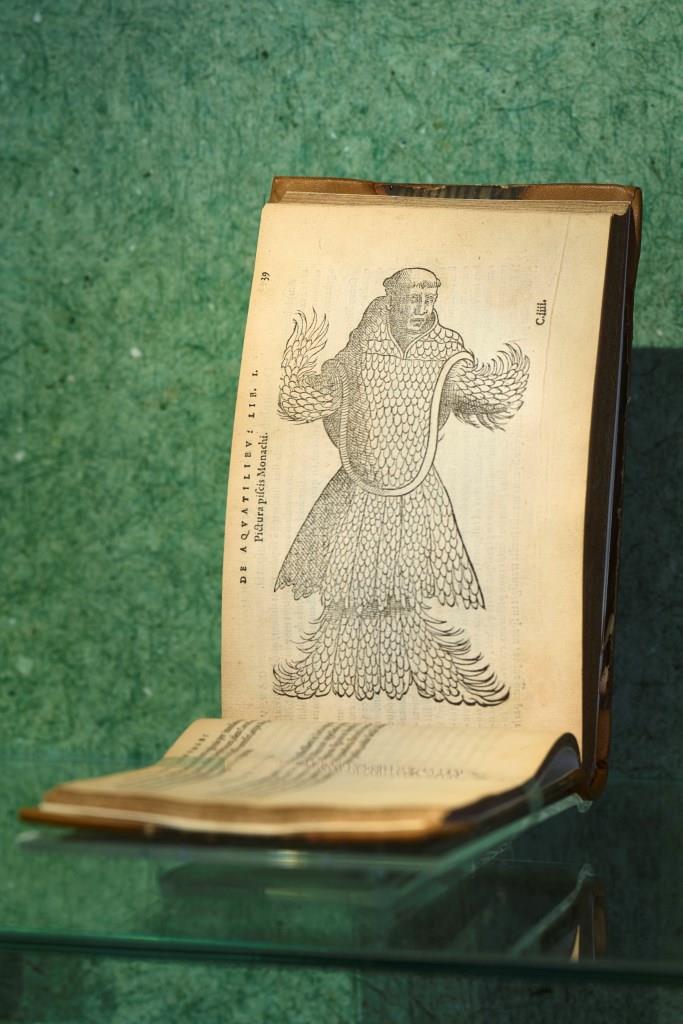

Belon was a French explorer and naturalist who categorised and described different species of fish and other aquatic animals in this book. Belon’s classification of animals relied on ancient texts, so his ‘fishes’ included otters, dolphins, chameleons and crocodiles.

Belon travelled all around Greece and the Middle East and most of his illustrations come from his own observations, but this book also includes mythical creatures or ‘monsters of the sea’. This illustration of the ‘sea monk’ was based on the animal that had been found off the coast of Norway in 1546. It was reported by the Danish King Christian III and the story become known across royal courts of Europe.

Several theories have been proposed to explain the appearance of the ‘sea monk’, like an angelshark, commonly called monkfish in English, or perhaps a walrus.

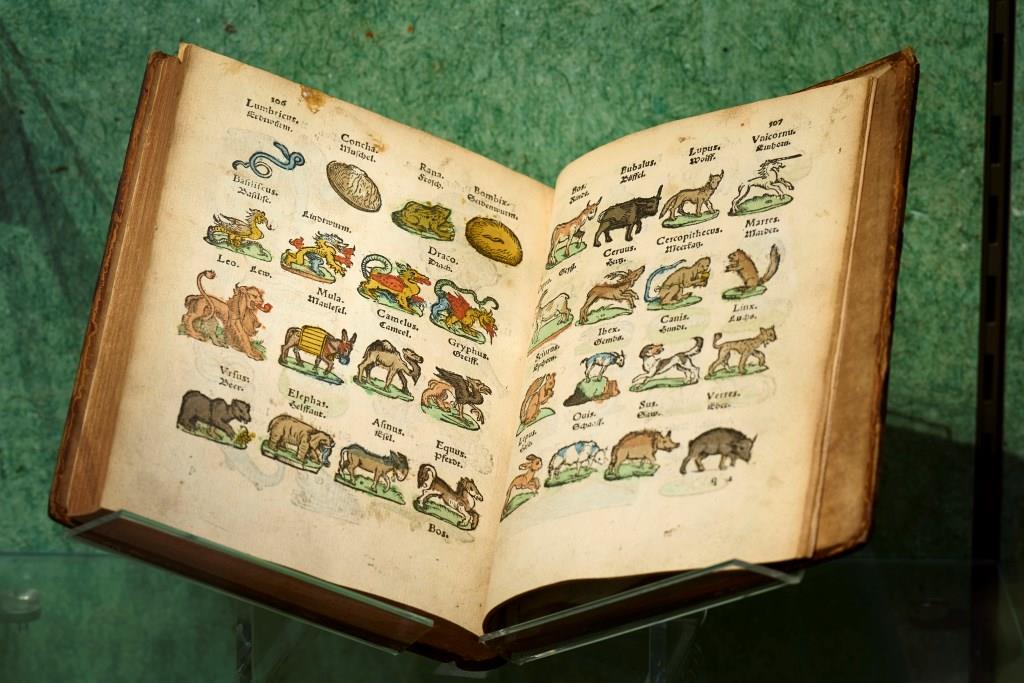

Egenolff was a German publisher who collected passages and images from other books and published them as his own. These publications were cheaper than the originals and became popular with the general public. This book contains depictions of both plants and animals. There are beavers, otters, squirrels, rabbits and other common and well-known animals, and mixed with them, there are mythical creatures like dragons, griffins and unicorns.

Egenolff was heavily criticized by his contemporaries for his many mistakes and sued for plagiarism. His defence was that nobody should have an exclusive right in depicting a specific natural thing, whether it is a plant or an animal, conveniently not mentioning that his images were copies taken from other authors’ books.

Centaurs were half-human and half-horse creatures from Greek mythology. Similar to satyrs, centaurs were said to be violent and savage, representing animal urges and the strife between barbarism and civilisation.

The most well-known centaur is Chiron, a very different centaur. He was wise, kind and civilised and was taught medicine and music by Apollo, the son of Zeus. In turn, Chiron had many students of his own, including Herakles, Achilles, Jason and Aesclepius, the Greek god of medicine.

The centaur Chiron is our College’s emblem and can be seen prominently on our logo.

The first recorded story about the existence of mermaids appeared in Assyria (now Syria) 3,000 years ago. The first Fiji (or Feejee) mermaid – the grotesque version of the mermaid like the one exhibited here – was made in the 1800s by sewing the top half of a monkey onto the bottom half of a fish. It was sold as a real mermaid supposedly caught near the Fiji islands in the South Pacific and ended up exhibited in the USA by politician and showman Phineas Barnum in his New York museum. To Barnum’s disappointment, naturalists he invited to examine it refused to confirm its authenticity and the mermaid was eventually destroyed in a fire at the museum. Since then, many mermaids like the original Fiji mermaid were made by craftsmen and fishermen and sold for commercial gain.

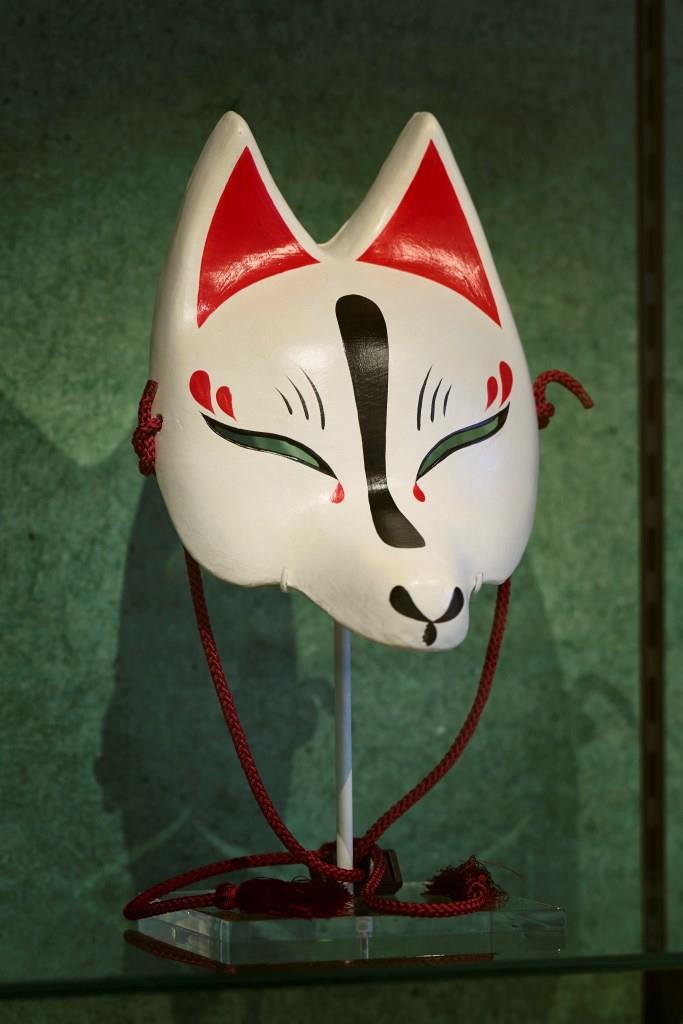

Various cultures across the world have worn specially designed masks meant to protect from evil spirits and promote healing.

The Kitsune mask is part of a Japanese tradition in which masks were worn to invoke the gods – in this case the Shinto god Inari, the god of rice, prosperity and fertility. Inari is often depicted with foxes and Inari shrines have statues of foxes on their grounds. Kitsune is a fox spirit, known for intelligence and a mischievous

nature. In Japanese folk stories foxes change shape in order to trick humans, but they also have other supernatural abilities that can help people and bring good luck.

There is a common thread running through many versions of fox legends in different cultures – the fox is often flexible, intelligent and cunning.

This blog was developed to accompany the exhibition Wild & Tame: Animals in History which runs from 19 July 2024 to 9 May 2025.

Follow our Twitter account @RCPEHeritage or our Facebook page or sign up to our newsletter to get notifications of new blog posts, events, videos and exhibitions.

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources