Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

The rituals that followed dying at home made death a community event up to the 1900s. Friends and family gathered to share stories and assist in the preparation of the body. The tasks performed were both practical and ritualistic. The corpse was washed and the limbs were straightened and tied together with string.

Fear of what could happen to the body was acute and not unwarranted. Those who could not afford a private grave were subjected to a pauper burial in ‘the pit’, which was little more than a hole in the ground where masses of bodies were packed. All burials were at risk of grave robbers, but the mass burials in pauper graves were particularly targeted.

Fear was further heightened by the passage of the Anatomy Act of 1832 which proclaimed that all unclaimed corpses were available to the anatomists for dissection. This definition of ‘unclaimed’ included the bodies of those whose families could not afford private burials.

The purpose of the frontispiece of a Renaissance scientific text was both to provide a guide to the book’s contents and to act as a marketing tool. Anatomical frontispieces often had a particular format – the author standing front and centre, leaning over a partially dissected corpse, while surrounded by his predecessors, peers and students.

This frontispiece shows the author Colombo, an Italian anatomist, physician to the Vatican and Professor of Medicine at the University of Padua. Colombo emphasised the importance of human dissection and criticised his predecessors, including Galen and Vesalius, for the errors they made due to using animals for study.

Colombo dedicated the final chapter of this work to the study of diseased organs, establishing the beginnings of morbid anatomy, or the pathology of diseased bodies.

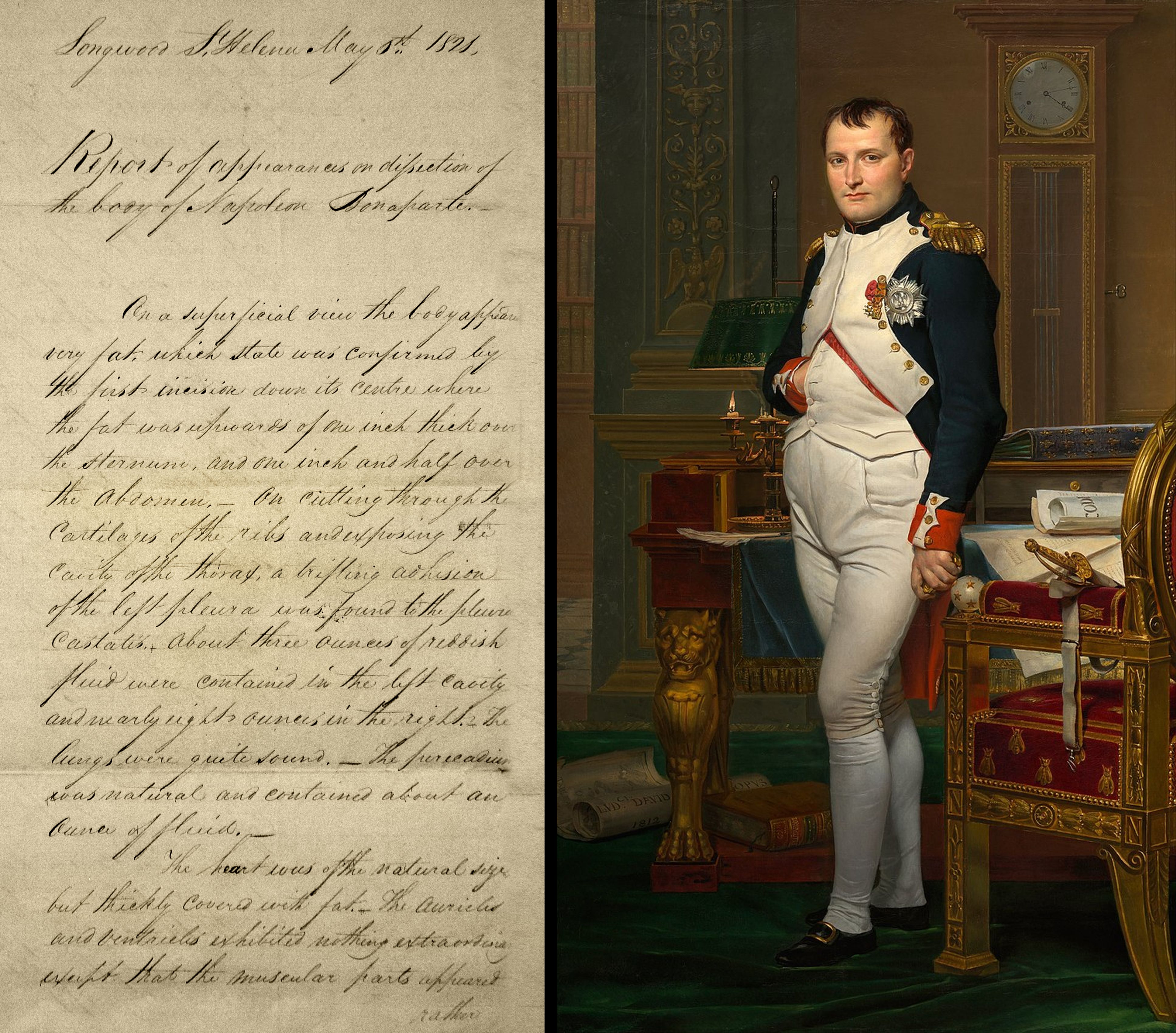

This report was written at Longwood House on Saint Helena Island where Bonaparte had been exiled since 1815, is an original copy, and is dated the day he died. The report identifies Bonaparte’s cause of death, saying that ‘The internal surface of the stomach… was a mass of cancerous disease’.

Although human dissections have a long history, the first recorded examinations of the interior of the body to determine cause of death only took place in the 1100s. Over the following centuries post-mortem reports began to be published and studied, and their structure standardised.

It was only really in the 1700s that it came to be understood that diseases were based in the organs and tissues, with specific signs and indicators of individual diseases starting to be identified.

This urn is made from olive pits and plant extracts. It is designed to be buried in the soil, where the nutrients from its organic shell are intended to encourage plant growth.

The first natural burial ground in Britain was established in Carlisle in 1993. Natural sites are defined by their creation and preservation of natural habitats and the minimisation of any environmental impact of the burials which take place there. Over 350 of these sites have now been established across the UK.

Many newer options could allow for even more environmentally friendly funerals in time, but most are still in the early stages of development. These include accelerated composting, burial suits designed to encourage decomposition and water cremation (which involves immersing the body in a tank of potassium hydroxide).

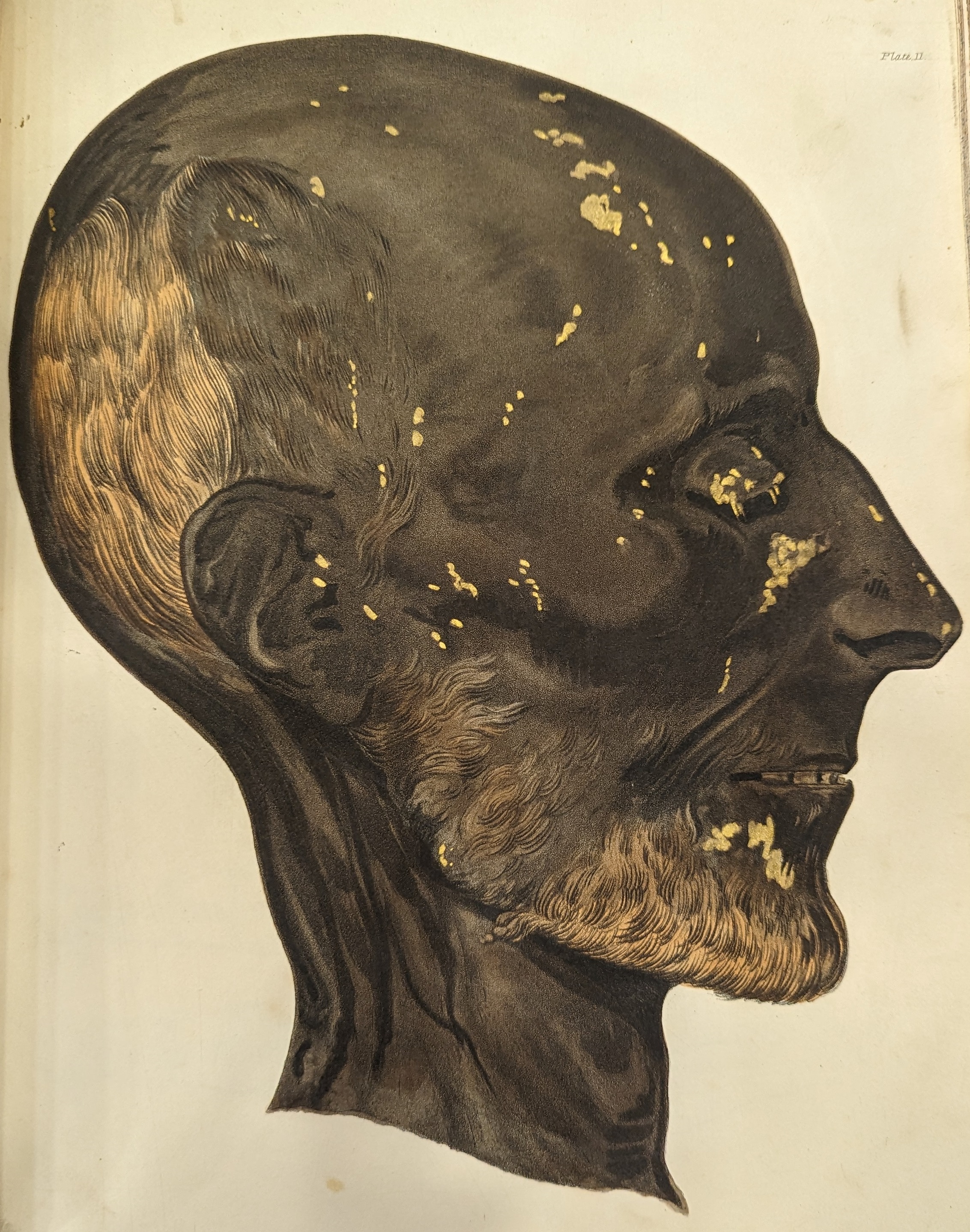

This volume illustrates the various methods of embalming bodies used by ancient Egyptians. The art of mummification is understood to have been to keep the body as intact and recognisable as possible.

The desire to preserve the body’s outward appearance was rooted in the necessity of maintaining the physical remains so the spirit could live on in the afterlife. Hot resin and the naturally occurring salt, natron, were used to prevent decay. Traditionally, the brains were removed via the nostrils, while other organs were either preserved in canopic jars or wrapped in linen and placed back into the empty abdomen. Canopic jars could be made of clay, wood, alabaster or limestone and were for the liver, stomach, lungs and intestines.

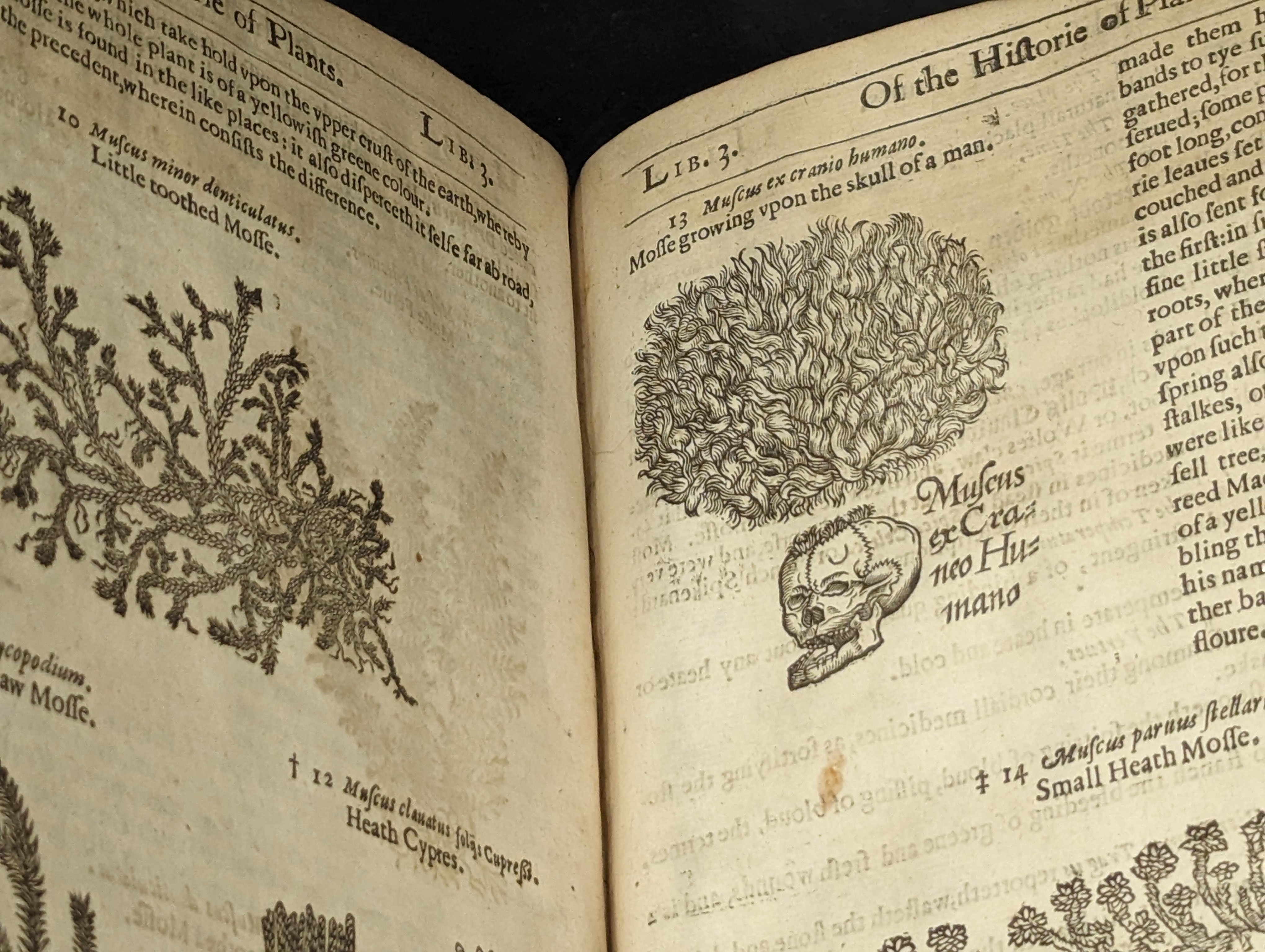

This illustration shows the medicinal uses of skull moss. Human skulls were a key ingredient in a form of treatment known as medical cannibalism. For hundreds of years, right up to the early 1800s, powdered skull could be found as an ingredient in printed and handwritten recipe books and was used as much by qualified practitioners as by folk healers. The skulls of executed criminals were believed to have particularly significant power.

Not only were skulls themselves used as ingredients, but the moss that grew on them when buried also appears in early treatments. Similarly to the powdered skull, this was believed to be more powerful when the person had died a violent death. Skull moss was most often used against nosebleeds or other sorts of blood loss such as battle wounds.

This blog was developed to accompany the exhibition After Life: A History of Death which ran from 27 October 2023 to 5 July 2024.

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories