Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

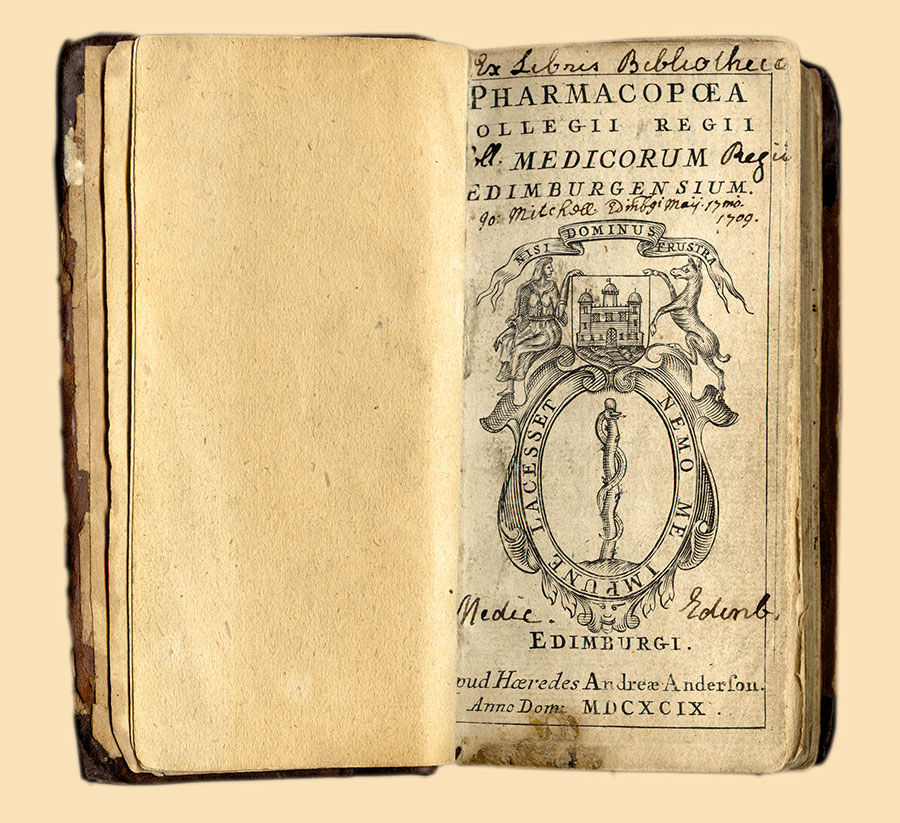

The beginnings of the Pharmacopoeia Edinburgensis are inextricably tied up with the founding of the College itself.

Before the existence of the Pharmacopoeia, there were no standardised recipes or methods of producing remedies for apothecaries, and no book or manual for physicians to consult when prescribing drugs or ointments. The move towards standardising medical teaching and practice was yet to happen, and this book acted as the first chain in that process of professionalisation.

In 1680 Sir Robert Sibbald had brought together a group of eminent physicians to discuss the matters of the day. If nothing else, they shared a commitment to science and medicine. Sibbald did not declare an intention to establish a college but the group helped promote the new physic garden at Holyrood and a number of members began to draw up a pharmacopoeia.

The Pharmacopoeia was top priority because all petitions for a Charter had highlighted the chaotic situation in the preparation and prescription of drugs and medicaments, conditions still prevalent in Scotland at the time. England was in a better situation due to its own Pharmacopoeia having been drawn up by the College of Physicians in 1618. Its jurisdiction over apothecaries did not extend further north than Berwick-upon-Tweed.

In March 1682 a committee of Fellows was selected to compile the first draft of the Pharmacopoeia. Little did Sibbald know it would take eighteen years to complete.

Publishing it was Sibbald’s driving force, and its delay was extremely frustrating for him:

‘In the tyme I was president…The Pharmacopoeia Edinburgensis was composed…and the Printer agreed to print it gratis…bot by the malice of some, it was laid aside for ten yeers therafter’ [from his Autobiography]

The longest-lasting of the college disputes was over the Pharmacopoeia. There were various factions and personal antipathies. Whigs were pitted against Jacobites and proponents of the ‘new science’ (amongst them Sir Archibald Stevenson and the Jacobite Archibald Pitcairn, who was already corresponding with Isaac Newton) argued bitterly with Sibbald’s gang, whose medicine was based on the works of Galen, and who were regarded as reactionaries.

Proponents of the ‘new science’ were opposed to the herbal remedies Sibbald was expert in, whilst on the other side any Newtonian remedies were rejected by Sibbald. The Fellows also disagreed on style and structure.

One of Stevenson’s party opposed its publication on the grounds that it was ‘barely a transcript of the London one, ill-copied and worse explained”.

Only in 1699 was a text produced that met with the approval of the College. This was made possible by suspending the Fellowships of the ‘moderns’, i.e. Pitcairn and Stevenson.

Thus the First Edition perpetuated some primitive remedies, such as dog’s dung and the skull of a murdered man.

The Pharmacopoeia was beset by politics and a power struggle between those old rivals, physicians and surgeons (including barber-surgeons and apothecaries). The Incorporation of Surgeons dreaded ‘that it might usher in a College of Physicians [that] would mightily encroach upon their privileges and tend to other prejudices’.

The practice of pharmacy had fallen into disrepute and the physicians were calling for a reform of the practice (with the support of the Town Council). The surgeons, as traditional keepers of pharmacy, resented this move and opposed the work of the Pharmacopoeia.

After the College was established, physicians wanted to abolish the practise of secret remedies. It meant inspecting and licensing shops and apothecaries, so the Pharmacopoeia came to be seen as a weapon of control over pharmacy. The Edinburgh College already had jurisdiction to do this but more guidance and control was needed.

There were major revisions in 1722, 1756 and 1774. They reflected the impact of emerging chemical and biological science. Successive editions were in general use in Scotland until 1864, when it was taken over by the British Pharmacopoeia. By 1750, most medical writing was now in English instead of Latin, but the Pharmacopoeia was still in Latin. Translations were made into English and many other languages.

The Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia 1699-1841

It had to be simple, clear, brief and accurate. It soon proved its usefulness to all, by meeting the needs of both pharmacists and physicians. It was a great enterprise which spanned 150 years and gave international fame and prestige to the College in its day, thus vindicating Sibbald despite an arduous and fraught battle to publication.

Author: Rachael Lloyd, Archive Volunteer at the Royal College of Physicians

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources