Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

Death is universal. But despite this, the way we view our own deaths, the way we prepare for, think about and respond to death, varies significantly.

In medieval times, particularly following the Black Death, reflections on mortality led to the proliferation of death-symbols (also known as memento mori). Death was uncomplicated, extremely ritualised and highly visible. Much of life was spent preparing for death, whether preparing your soul, preparing your successors, or preparing your inheritance.

As science has enabled longer life spans, so death is pushed farther away, becoming more remote. The responsibility for understanding death has moved from the philosopher and the cleric to the scientist and the physician. The acceptance, and even perhaps fatalism, of the past has given way to an unwillingness to accept death. Many of us avoid talking about, or even thinking about, dying. And so, we are less prepared practically, financially, or emotionally, when our time comes.

Dying is a process, not an event. Exactly when the moment of death occurs is a matter of opinion, not fact. Death has variously been defined by an absence of heartbeat, lack of consciousness and by the cessation of all electrical activity in the brain. In medieval Europe a candle would be held to the mouth, if there was no breath to disturb the flame then the person would be declared dead.

In 1800s Germany the dead were kept under supervision in ‘corpse houses’ until putrefaction set in, to avoid premature burial. Wakes served a medical as well as a spiritual purpose – keeping the body under surveillance for three or four days ensured that any signs of life were observed. Fear of premature burial was common, and campaign groups included The London Society for the Prevention of Premature Burial, founded in 1896, which argued that over 10 per cent of people were buried alive.

This book explores numerous stories of people being buried alive. Its author, Jacob Winslow, a Danish-born French anatomist, suggests a number of tests to ensure the individual is dead prior to burial – including pouring ‘vinegar and salt or warm urine in the mouth’ and putting ‘insects in the ear’.

Fear of premature burial, known as taphophobia, peaked in the 1700s and 1800s. Changing death rituals, particularly the reduction of wake traditions, led to the fear that signs of life would be missed before burial.

A number of elaborate coffin mechanisms were patented which allegedly would resolve this issue, including ones with speaking tubes, glass lids, or a cord attached to a bell. There is no evidence that any of these so-called safety coffins ever saved a prematurely buried person.

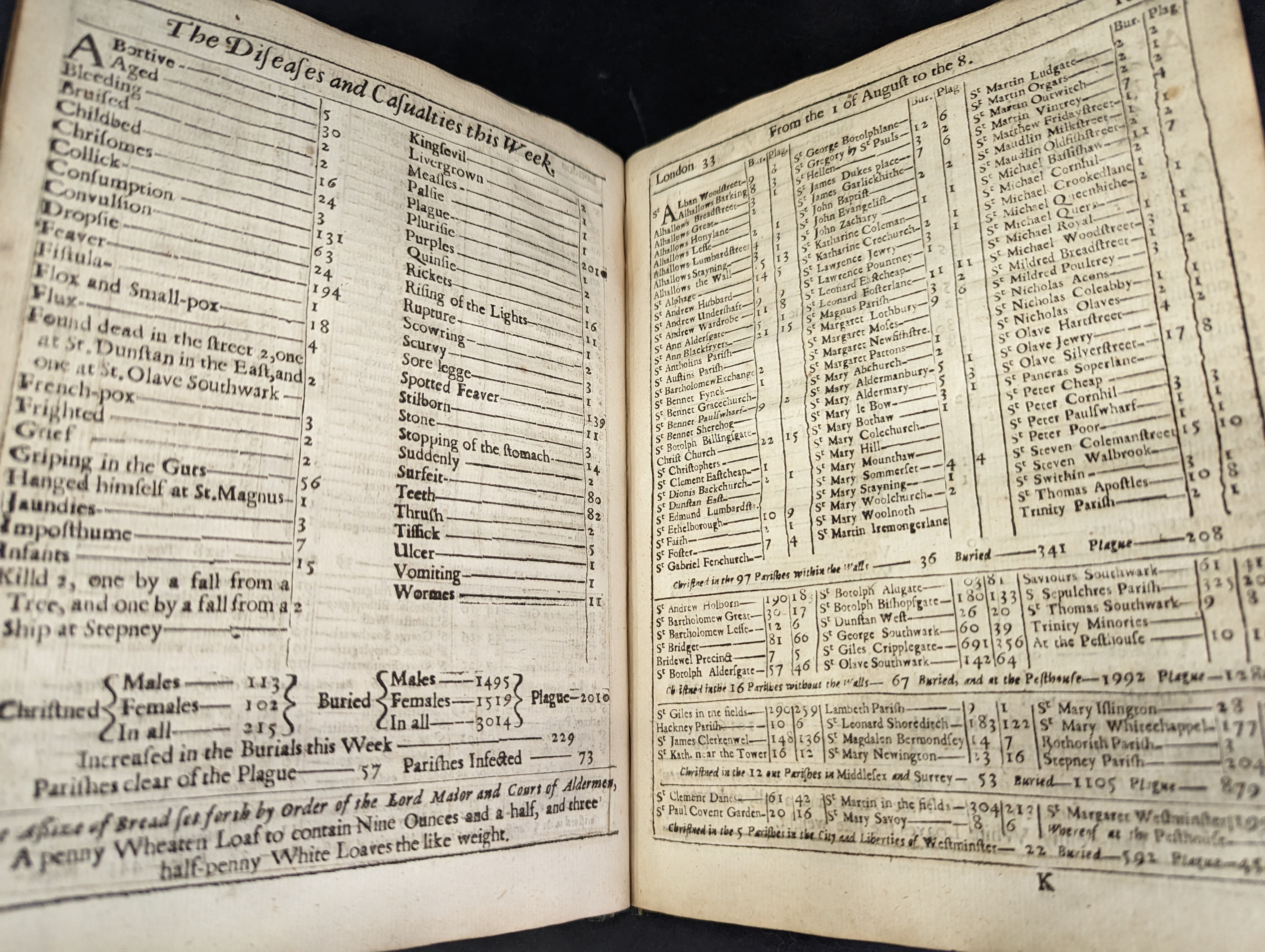

This volume collects together the bills of mortality printed in London during the plague of 1665. Because it was not a legal requirement to report deaths at this time, local officials employed searchers to locate the dead. These searchers were usually older women, poor, illiterate and untrained.

The challenge of making sense of these records is shown by just this one page. Sometimes respiratory conditions were called ‘Tissick’, sometimes ‘Rising of the Lights’. Dysentery could be ‘Scowring’, ‘Flux’, or ‘Griping in the Guts’. One contemporary noted that ‘The Old-Women Searchers after the mist of a Cup of Ale, and the bribe of a two-grout fee’ would agree to misreport syphilis cases and ‘only hated persons, and such, whose Noses were eaten off were reported to have died of this too frequent Malady.’

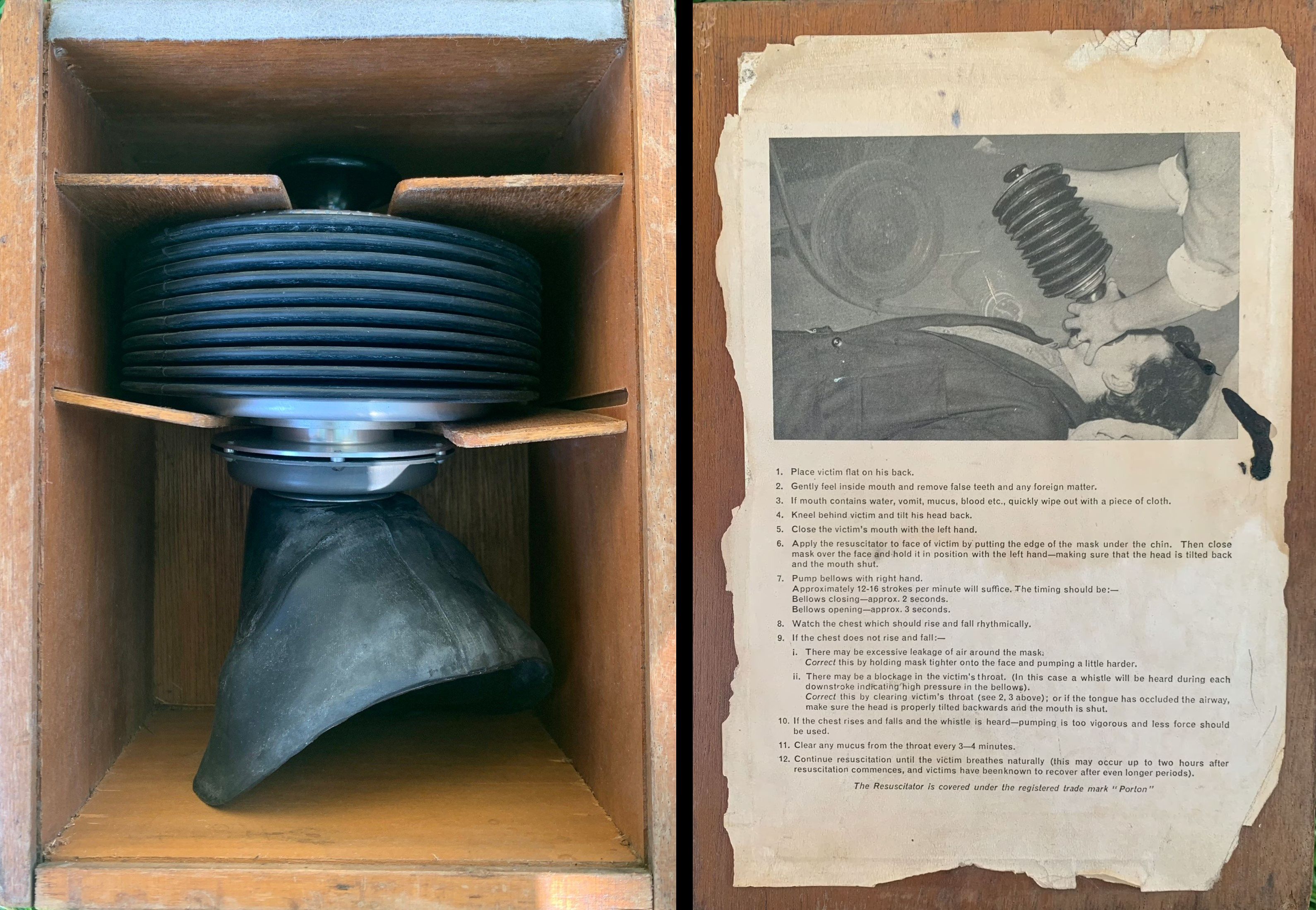

This resuscitator was developed in the 1950s for industrial use. This model was designed to be used in factories for workers who had stopped breathing, as well as for emergency resuscitation in hospital wards and for the air transport of polio patients.

Once the airway is cleared the mask is placed over the mouth and nose and the bellows are pumped to force air into the lungs. The instructions warn that it can take up to two hours of continuous use to revive the afflicted person.

Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation had been used as a method for revival for hundreds of years. But it was only in the late 1700s that oxygen was discovered, and only over the following decades that its purpose was understood. It was this understanding that led to the development of the artificial respirator.

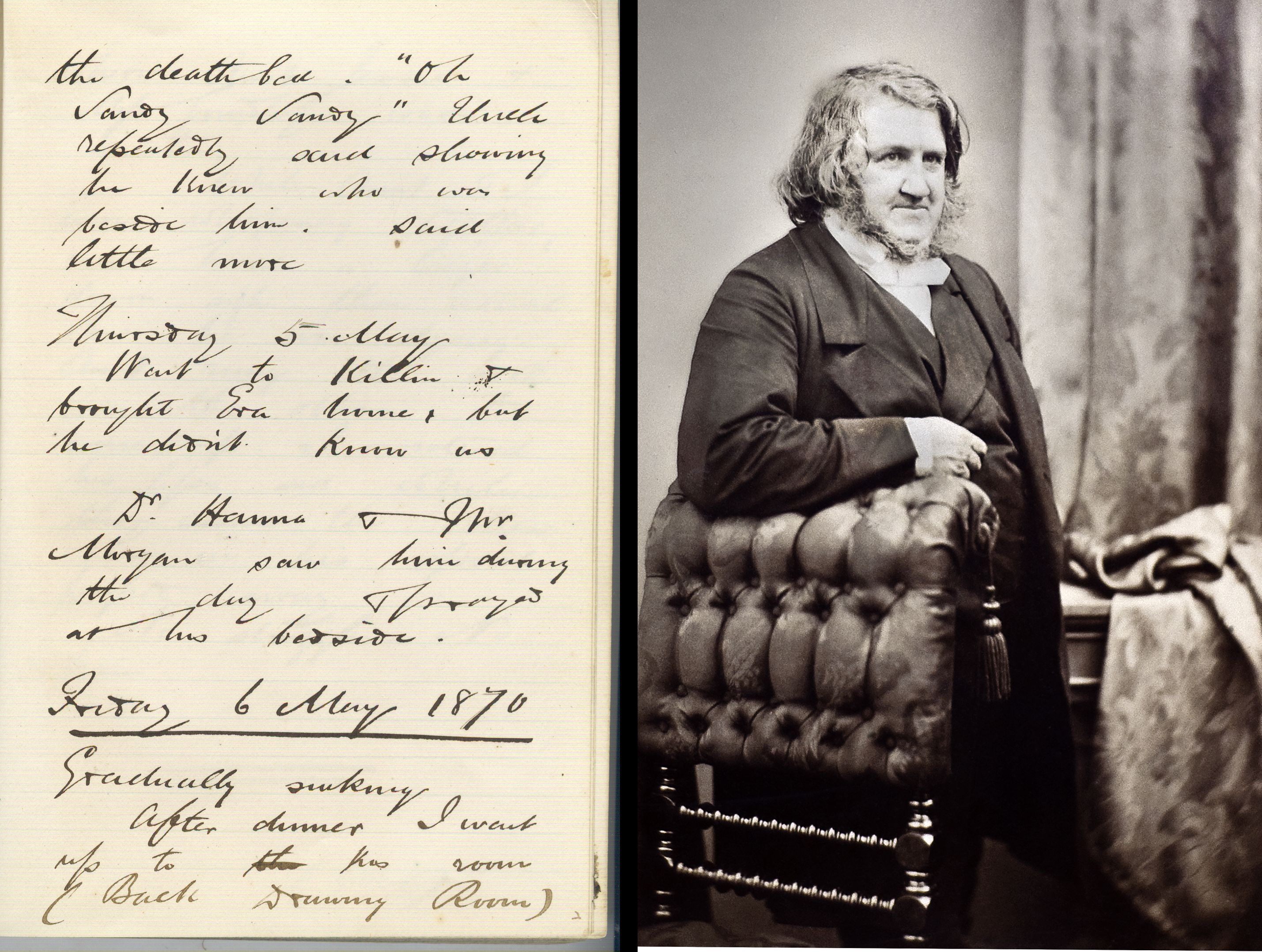

This diary details the final illness of James Young Simpson, President of our College, Professor of Midwifery at the University of Edinburgh, and celebrated promoter of chloroform as an anaesthetic.

Written by his nephew Robert, the diary gives an account of the last two months of Simpson’s life. It outlines the onset of his illness, what books he liked read to him, and near the end, it describes how his elder brother sat through the night cradling him in his arms.

‘It was most touching to see the elder brother watching by the death bed. “Oh Sandy, Sandy,” uncle repeatedly said showing he knew who was beside him.’ The final entry reads: ‘I moistened his lips, and while the others came in his spirit passed away. No struggle – no pain.’

This blog was developed to accompany the exhibition After Life: A History of Death which ran from 27 October 2023 to 5 July 2024.

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories