Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

This project, carried out in collaboration with the University of Glasgow, has created an online digital edition of the medical correspondence of Dr William Cullen (1710-1790).

Cullen was the most influential medical lecturer of his generation, who drew thousands of students to the Edinburgh Medical School. As the pre-eminent Scottish medical figure of his day, Cullen’s opinion was in high demand and people wrote to him from around the world requesting his advice on treatments.

Unusually, Cullen retained all his letters and responses, which together form a remarkable collection of over five thousand items, all held here in the College archives.

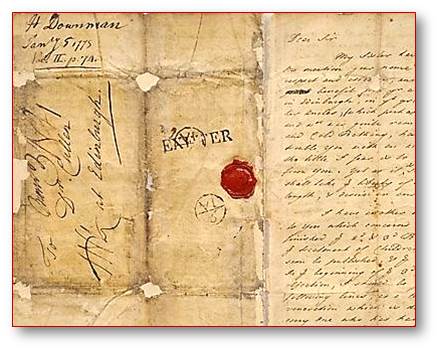

Cullen’s correspondence covers a range of social classes and geographical locations. A Scottish plantation owner writes from Charleston asking how to cure an American slave’s epilepsy, there are enquiries about a Russian Princess with gout and a patient who became ill after eating a surfeit of cucumbers. Famous patients include the dying Samuel Johnson - James Boswell writes asking asks Cullen for advice.

While Cullen’s advice as a respected practitioner reveals his modern-sounding concerns with the health benefits of diet, exercise and travel the letters also detail a range of more unusual treatments, including cold bathing, purges, vomits, issues, flesh brushing and leeches for conditions that range from fevers and colics to horrors, scabs, teethings and deleriums.

By the 1770s Cullen’s stature as a professor of medicine and clinician was unrivalled in the English speaking world and an increasing numbers of letters seeking his advice arrived at the comparatively modest house in Mint Court on the Cowgate that he shared with his wife, seven sons and four daughters.

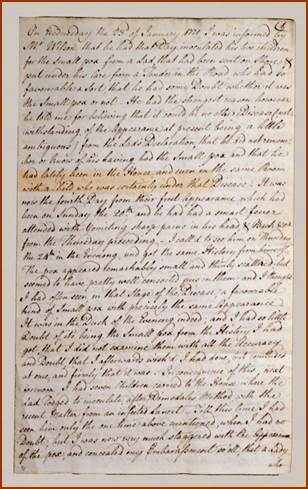

Medicine by post was common in the eighteenth century. Travel was difficult, physical diagnosis rudimentary, and laboratory medicine non-existent. As a result a fair description of somebody’s complaints was thought sufficient for a tentative diagnosis and the institution of treatment.

Many of Cullen’s patients were suffering from chronic diseases, some of which are now considered as diseases of affluence. Cullen’s answers are directed to the individual patient’s needs rather than to a specific disease.

Cullen usually rose every morning about a quarter to seven. With the help of a secretary he would read the letters received the previous day and then swiftly compose his replies until about 9 am when he would visit his Edinburgh patients.

Most of the inquiries were answered within a day, and Cullen was often praised for his prompt response.

His standard charge was two guineas (very roughly £250) but this was not fixed and the fee depended on patient's ability to pay.

Initially Cullen's consultation notes were copied before being mailed, but after 1781 Cullen used an early copy machine designed by another friend, the inventor and engineer James Watt. To use Watt's copy machine you pressed a thin, moistened paper over the original letter which was written with a special ink; the ink was absorbed from the original document onto the moistened paper producing a mirror image which you then read through the thin copy paper.

Joseph Black was the first to hear about the copying machine and it is repeatedly mentioned in subsequent letters between the two. Watt formed a new company to exploit the discovery and launched an aggressive marketing campaign. He demonstrated the machine to bankers and members of Parliament and sold more than 150 presses in the first year. Black, writing to Watt from Edinburgh on 7th January 1780, declares: “Since my last I have found two gentlemen who wish to be possessed of your secret for copying writing – Mr Adam Smith who is now a Commissioner of the Customs here and Doctor Cullen to whom it will be extremely useful”.

Cullen’s last consultation letter was dated December 26, 1789, and was addressed to a William Charters, who suffered from spasmodic asthma. A month earlier Cullen had confided to an Irish colleague that he was not feeling well and he resigned his chair at the University.

You can find the digitised Cullen collection online here

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources