Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

The College had twenty-one original Fellows (the most senior level of associate) when it was formed in 1681.

College Fellowship served a very practical purpose – you needed to be a Fellow in order to legally be allowed to practice medicine within the city of Edinburgh. But it was also useful for other reasons - it helped to convey prestige on the holder, and would have helped to impress potential patients.

Even if you were further afield and didn’t technically need to hold that title to work, it would definitely have done your career no harm to have FRCPE after your name. It would also have helped to distinguish you from the many charlatans and faith healers, who served as your competition during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Our Fellows worked within the College for the advancement of medicine, and also externally – for the Universities of Edinburgh and Glasgow, the Scottish infirmaries, and further afield. Some of the most significant medical figures in this country for over 300 years have been Fellows of this College.

A medical career, and by extension Fellowship of the College, could often be a family tradition.

One James Lind petitioned for Fellowship in 1769, twenty-one years after a relative of the same name. The older Lind is known as the pioneer of the clinical trial for his study of scurvy in the navy, which had resulted in the theory of citrus fruits as the cure. The same research also resulted in arguments for improved ventilation, cleanliness, and more hygienic clothing for naval sailors, all of which would seem standard now.

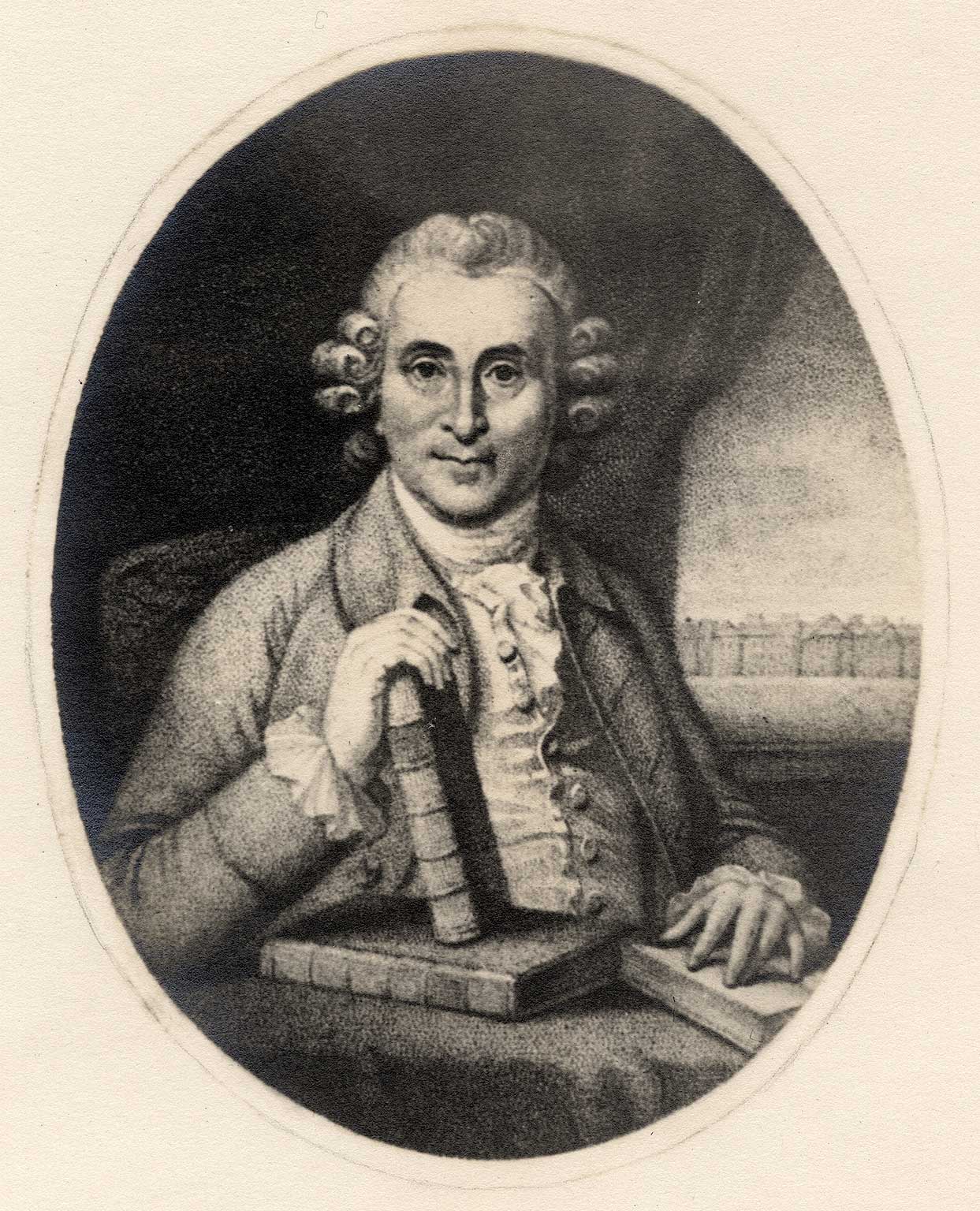

The elder James Lind

Lind was elected as a Fellow of the College in 1750 and became Treasurer in 1756. The second Lind was admitted as a Fellow in 1770, and went on to have an illustrious career - travelling with Joseph Banks on his expedition to Iceland, being the first to map Islay in the Hebrides, and became physician physician to the Royal Household at Windsor.

Black was initially Professor of Anatomy and Chemistry at the University of Glasgow, later becoming Professor of Medicine and Chemistry at the University of Edinburgh. He was granted Fellowship in 1767 and was President of the College from 1788 to 1790.

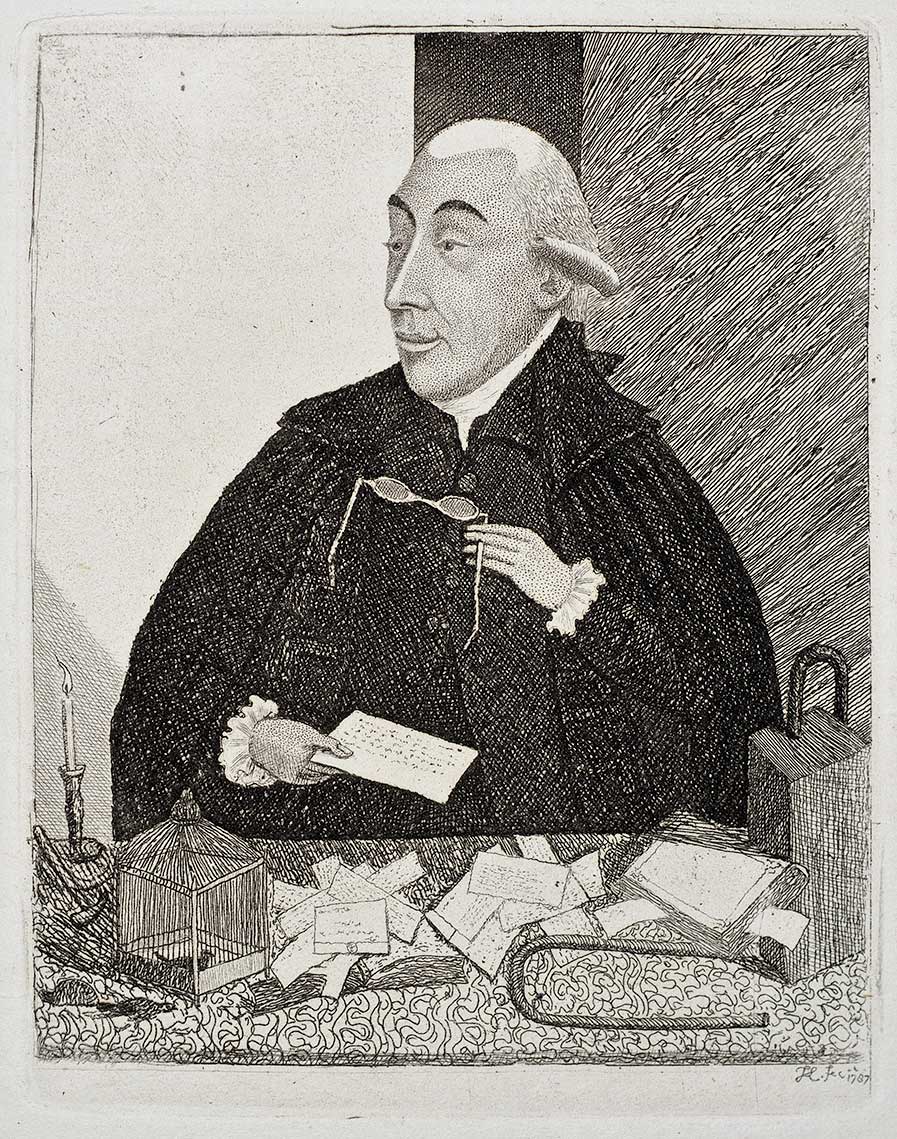

Joseph Black, 1787

He is particularly known for his discovery of what he called ‘fixed air’, and which we now know as carbon dioxide. He observed that it was denser than air, and that in its pure state a candle could not burn in it, nor animals survive in it. He also went on to demonstrate that it was produced by animal respiration and microbial fermentation.Black then passed the cumulation of his research on to one of his students, Daniel Rutherford. He in turn continued the experiments – keeping a mouse in a space with little air until it died, then burning a candle in the remaining air until it went out. Further study showed that there was an element of the air which was not carbon dioxide, but which could not support flame nor life. This he called ‘noxious air’, but came later to be known as nitrogen.

Bust of Daniel Rutherford

Rutherford became a Fellow of the College in 1776, and served as President from 1796 to 1798.

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources