Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

Beliefs about health and disease are seldom unique to one society, for they tend to pass from one community to another by word of mouth and the tales of itinerant travellers. Thus, for example, eating a mouse was considered a cure for bed-wetting throughout Europe in the Middle Ages but there were local variations: in the North of Scotland, the custom was to eat the mouse from a spoon made of horn taken from a living animal - 'a quick horn spoon'. In Scotland the line between Highlands and Lowlands was never precisely defined in cultural terms and there was always some intermingling of ideas, especially in the marginal areas of Atholl, Angus and Mar. However, certain practices are recorded as having been widespread in the Celtic highlands and may therefore be considered as characteristic in their detail if not unique in concept.

In the early Celtic world, there was general belief in the supernatural - fairies, demons and the threat of the evil eye ('droch-shuil') and there were certain people who were believed to have occult powers while others were able to exorcise evil spirits. These beliefs were complemented by a deep knowledge of the therapeutic properties of plants, animal products and other materials, even water. The wise women and other gifted individuals would use these medicinal substances in combination with charms and incantations in the treatment of disease.

A great variety of plants was used in Celtic medicine and there was a general familiarity with common herbs. Some of these were undoubtedly of real value, though many were probably ineffective and achieved any perceived result through the belief of people in the accompanying charms and spells. Thus a poultice of hemlock applied to a skin cancer with the appropriate incantation was believed to remove the growth, at least in some cases.

Certain plants had a general application, such as the medicinal tea made from the common speedwell. Others were reserved for particular conditions. The juice of juniper berries was thought to be effective in curing epilepsy. Infusion of wild garlic was one of many remedies for bladder stone and infusion of tansy got rid of intestinal worms. Figwort was widely used for healing cuts and sores: it was called the plant of the thunderer ('lus an torranain') after Toranis the Celtic god of thunder, who gave his name to the island of Taransay. Some plants were used for magical purposes. For example, the sap of the rowan tree (mountain ash) was given to newborn infants to ward off evil spirits.

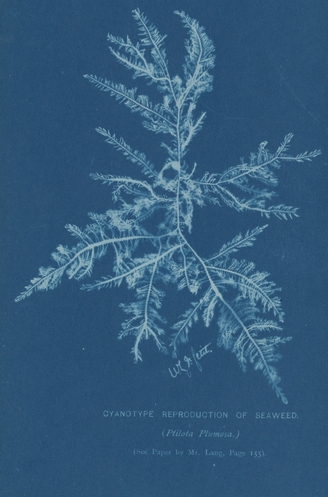

In Skye, seaweeds such as dulse were used as treatment for headache, colic, constipation and worms.

Eating a mouse to cure bed-wetting has been mentioned and many other animals had specific uses. A common belief throughout the British Isles was that whooping cough could be cured by passing the sufferer under the belly of a horse, when the disease would be transferred to the animal. In most areas a piebald horse was specified but in the Celtic world it had to be a white horse, perhaps in contrast with the malevolent black water horse, the mythical kelpie. The Celtic Scots also believed that asthma could be alleviated by smearing deer grease on the soles of the feet, whereas the Irish considered a dandelion potion to be more effective.

In the Western Isles, the ubiquity of seals meant that products of these animals were used for many purposes. The wearing of a sealskin girdle resulted in the relief of sciatica and the fresh flesh of young seals was given for diarrhoea. In St Kilda, the fat of seafowls ('gibean') was used to heal wounds and this 'gibean of St Kilda' was highly prized in Skye and other islands for the same purpose.

In his book 'Carmina Gadelica' Carmichael listed large numbers of runes and incantations in Gaelic, each of which was appropriate to a particular situation or disease. There was a widespread Celtic belief that fairies were especially predatory around the time of childbirth and it was customary to put a piece of cold iron in the mother's bed to prevent abduction of the mother and her baby. The newborn infant is still vulnerable to evil spirits until baptism, which should therefore be undertaken as soon as possible. Neonatal convulsions were thought to represent struggles to escape the fairies' clutches. It was generally believed that, if a baby arrived feet first, he was born to be hanged and that, if the fingernails were cut before one year of age, he would become a thief.

In later life a charm ('sian') could be put on someone to protect him from injury, perhaps in battle, or to ward off the ill-effects of the evil eye. Exorcism of demons was often undertaken with various specialised rituals for the demons of jaundice, epilepsy, erysipelas, local infections such as styes and so on. A magical cure for epilepsy was to bury a black cock at the spot where the patient had had his last fit.

Rickets and the resulting deformity were common in mediaeval Scotland and became even more widespread as diets deteriorated after the 18th Century. It was generally believed that blacksmiths, particularly if descended from several generations of smiths, possessed preventive and therapeutic powers, provided that an exact ritual was followed which varied in different areas. According to the practice of 'laying' in the Highlands, the rickety child was washed with special water before sunrise and then placed with due ceremony on the anvil, when the smith passed his tools three times over the child.

Plant, animal and magical cures were commonly combined with water, often administered three times. However, the medicinal qualities of water alone were highly regarded, especially if it came from a particular river or well. In Ireland, drinking water three times from certain rivers was thought to be effective in mumps. Therapeutic properties were attributed to special wells in the Highlands, such as the Well of Balquhidder, which was reputed to cure whooping cough, and a well at Borve in Harris, which was efficacious against 'stitches and gravel'. A well in North Uist ('tobar an deididh', well of the toothache) gave complete relief from toothache if three draughts of water were drunk in quick succession. Wells were often identified with local gods and the healing properties attributed to these deities.

The Water of Life - 'uisge beatha' in Gaelic, usquebaugh in Scots and whisky in English - was understandably considered to be almost a panacea, given for a variety of ailments but believed to be specific for smallpox. In 1785, the right of Forbes of Culloden to distil duty-free whisky at Ferintosh in Cromarty was withdrawn by law, which prompted Robert Burns to write:

Thee Ferintosh! O sadly lost!

Scotland lament frae coast to coast!

Now colic grips an' barkin' hoast

May kill us all!

Clearly confidence in the medicinal value of whisky endured in Scotland long after the Middle Ages.

No doubt many early Celtic leeches used plant and animal products in good faith and believed in their efficacy, though later generations of physicians relegated them to folklore. Conversely, however, some ancient Celtic remedies, such as giving the thyroid gland of a sheep born on St Brigit's Day to a child with cretinism, may have been compatible with the scientific facts that form the basis of modern therapeutics.

Author: Dr Ross Mitchell, Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources