Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

Botany can trace its roots back across millennia and is intertwined with horticulture, biology and medicine. In fact, some of the earliest medical texts were so-called ‘herbals’, which contained descriptions of plants and which ones could be used to heal certain illnesses. Not many of them contained accompanying detailed illustrations, however. Predating even these are examples of drawings and illustrations of various plants and trees from around 4,000 years ago in Mesopotamia and Egypt.

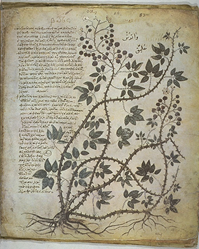

When looking through some examples of botanical art and illustrations, it becomes clear that the methods have changed somewhat over the centuries. They differ in the level of detail and accuracy, they are embellished or humanised (e.g. mandrakes made to look like humans, or the methods of illustrating change, for example from manuscripts to movable type and woodcuts. One particularly influential person mentioned frequently in ancient manuscripts is Greek physician Krateus, who is often credited as the “father of botanical illustration”. Unfortunately, none of his work survives and the earliest surviving illustrated manuscript is a copy of De Materia Medica by 1st century AD Greek physician and botanist Dioscorides. It was re-copied and re-copied for over a millenia, well into the Middle Ages.

A development in the 1400s that made it slightly easier to copy illustrations was woodblock printing. A woodblock cutter would use an image of the plant drawn by the illustrator and carve it into a flat wooden block. This was then inked and pressed onto the paper. Woodblocks could, once cut, be used in different places of a book, combined with other cuts or reduced to individual parts that could replace another to indicate a plant’s variation. This, together with movable type printing, made it possible for botanical knowledge to be shared more broadly. In fact, around this time many herbals were meant for people who possibly had no access to a physician and frequently they were published not in Latin but in languages or dialects the general public spoke.

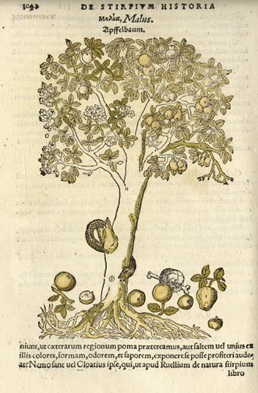

Many herbals produced before 1500 were collated from different ancient sources that had been copied down throughout the centuries and not a lot of their content was newly researched. An important early herbal in our exhibition is Hieronymus Bock’s (or Hieronymus Tragus) herbal Kreuterbuch (1546). While the first edition did not have any illustrations, likely for financial reasons, Bock took care to describe the plants in German and to a great level of detail. Only later editions were translated in Latin and included illustrations [see picture] by one of the pioneers of European botanical illustration, David Kandel, as well as copies of woodcuts for works by Otto Brunfels and Leonhart Fuchs, both also considered to be “German Fathers of Botany” like Bock himself.

With the common practice of copying woodblocks, possibly already coloured ones, and reusing them in other works brought up the issue of copyright of botanical illustrations. Christian Egenolff (1502-1555) was a publisher, rather than a botanist, and printed a herbal ‘allegedly’ containing illustrations done by Hans Weiditz (see picture of black hellebore in Brunfels’ work) and annotated by Otto Brunfels. The publisher of this work, Herbarium vivae icones, was Johann Schott, who went on to sue Egenolff for plagiarism. The original work was considered a new era for scientific publications, showing plants in different stages of growth and in great detail, and would later be seen as a model for similar illustrated volumes in Germany after this time. One of Egenolff’s main responses to the allegation was that the copies were of the plants and not of the illustrations - copyright did not apply to plants. Generally, Egenolff's work was said by his contemporaries to include some of “the crassest errors” and was heavily criticised.

Fuchs was vocal about the importance of colouring in telling the difference between plant species. As early as Greek antiquity, physicians differentiated between various colours of plants that caused conditions in the human body. The colouring process did make the printing process more expensive on the whole, and coloured copies could be specifically requested by buyers and publishers. Even more expensive and time-consuming was hand-colouring botanical illustrations, instead of using coloured woodblocks. One example for hand-coloured illustrations in our Physicians’ Flowers exhibition Elizabeth Blackwell’s illustrations in A Curious Herbal.

With the expansion of colonialism and travel beyond European borders also came the confrontation of botanists and physicians with new types of plants, which illustrators were keen to draw and document. For example, Maria Sibylla Merian, a German-born illustrator, travelled to the Dutch colony of Surinam and recorded tropical insects, such as the lifecycle of native butterflies, and these drawings were often set against illustrations of their host plant (see picture). She was later considered one of the greatest botanical illustrators of all time.

While it can be said that the recording of plants’ appearance for medicinal or scientific purposes was somewhat taken over by photography, botanical illustration is by no means a dying art. Aberdeen-born Mary McMurtrie (1902-2003) was internationally recognised for her botanical art, which started through watercolour paintings, and she went on to publish her first book, Wild Flowers of Scotland, aged 80. She could be considered one of Scotland’s finest botanical artists of her time.

For keen artists nowadays, there are options for taking your illustration skill to a professional level with a Diploma in Botanical Illustration from the Royal Botanic Gardens in Edinburgh, for example.

Author: Isabel Lauterjung

References and further reading:

- A Brief History of Botanical Art - Jutta Buck and Cynthia Rice [https://www.asba-art.org/about-botanical-art/history-0]

- The History of Botanical Illustration and Why It's Still Blooming [https://mymodernmet.com/history-of-botanical-illustration/]

- Kusukawa, Sachiko. 2012. Picturing the Book of Nature: Image, Text, and Argument in Sixteenth Century Human Anatomy and Medical Botany (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

- Michael North’s posts on herbals (from the Historical Collections of the National Library of Medicine)

→ https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2015/05/14/the-earliest-herbals/

→ https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2015/07/09/medieval-herbals-in-movab…

→ https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2015/09/29/a-german-botanical-renais…

→https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2016/01/06/research-reborn-dioscorid…

→ https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2016/03/22/colonialism-and-the-plant…

→ https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2016/04/14/some-of-the-most-beautifu…

- A passion for plants: botanical illustration by women artists

- Joseph Leo Koerner. 1993. The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press)

- https://llandudnomuseum.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Botanical-Illu…

- https://museum.wales/articles/1262/A-passion-for-plants-botanical-illus…

- https://www.myartteacher.com/botanical-art-and-the-woodcut/

Image sources:

Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Materia_medica#/media/File:ViennaDioscori… [Licence: Public Domain]

From Bock’s De Stirpium Historia [College’s exhibition material]

Black hellebore from Brunfels’ work: https://www.botanicalartandartists.com/news/black-hellebore-herbarum-vi…

Merian’s morphosis insectorum Surinamensium

[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Merian_insectes_Surinam.jpg]

Licence: Public Domain

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources