Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

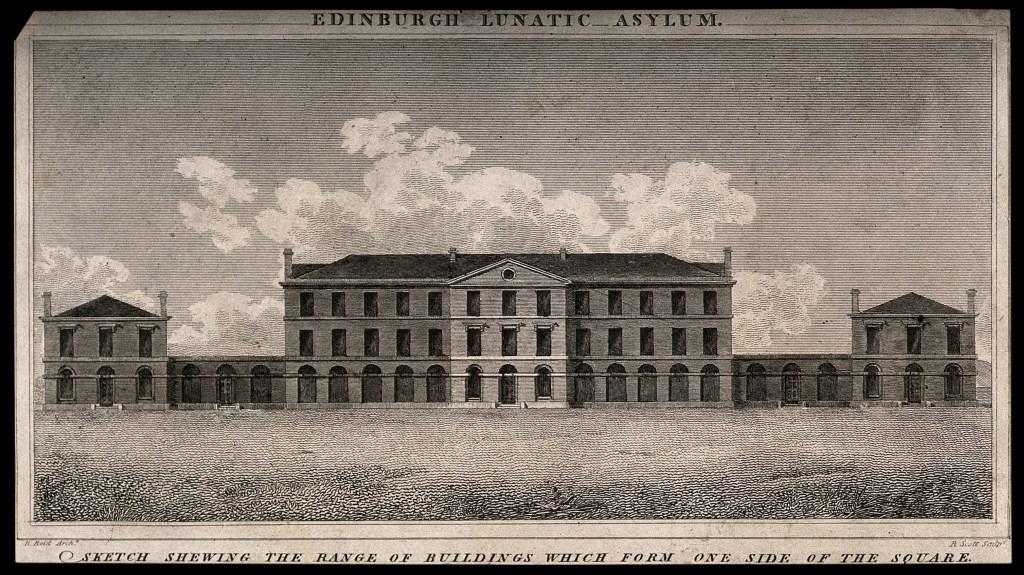

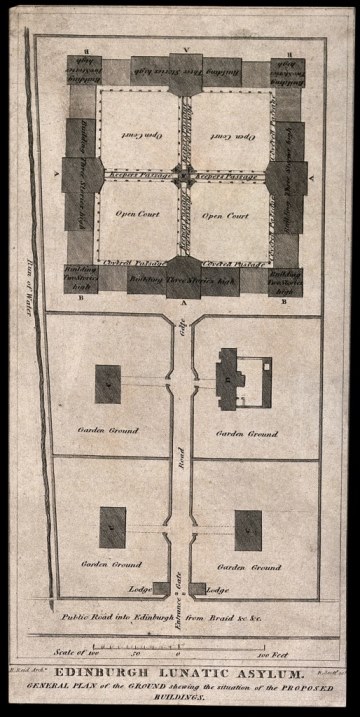

On the 8th June 1809, the foundation stone of the then-named Royal Edinburgh Asylum was laid in the hospital grounds at Morningside, marking a turning point in the history of mental illness in Edinburgh. On this stone were engraved the words Orandum est ut sit mens sana in corpore sano, a quote from Juvenal meaning that one ought to pray for a healthy mind in a healthy body. A long way from the chains and fetters which were once used to contain patients with mental health problems, the Royal Edinburgh Asylum was founded as an institution with humanity, kindness and holistic medical treatment in mind.

The path to creating an institution to treat people with mental illnesses in Edinburgh was not smooth, with seventeen years passing between the first appeals for funding in 1792 and the laying of the foundation stone in 1809. Dr Andrew Duncan, President of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (1790 to 1792; 1824 to 1825) stated that he was originally inspired to establish an asylum in Edinburgh because of the death of his patient and friend, the poet Robert Fergusson.

Bronze statue of Scottish poet Robert Fergusson on the Royal Mile, Edinburgh.

Fergusson died in the Edinburgh City Bedlam and Duncan had been appalled to find Fergusson living there in a “deplorable condition, subjected to furious insanity” due to a head injury he had received by falling down some stairs. After witnessing the poor conditions and treatment of people with mental health problems in Edinburgh, Duncan became determined to establish a more appropriate institution – the asylum that would become the Royal Edinburgh Hospital.

Portrait of Andrew Duncan by Henry Raeburn.

On the 26th January 1792, Duncan officially launched the first appeal to the public for subscriptions, legacies and donations to help fund his vision for an asylum in Edinburgh. Despite fourteen years of appeals by way of letters written to the government and pamphlets published outlining Duncan’s intentions for the asylum, only £100 was raised from public subscriptions and £25 from the Royal College of Physicians. This lack of interest may be attributed to a number of factors including the ongoing French Revolution. Finally, in 1806 the sale of a number of forfeited Jacobian estates provided Duncan and the managers with enough money to buy land in Morningside and start constructing the first asylum building, known as East House.

Four years after the foundation was laid, the first patient was admitted on the 19th July 1813. At first, the asylum was only able to admit paying patients, but after the hospital received a Royal Charter from Queen Victoria in 1840 and the institution was renamed ‘The Royal Edinburgh Asylum’, the hospital started to admit so-called ‘pauper patients’ who were sponsored by their local parish churches. Over the next century, numerous government Acts were passed to regulate the care of those with mental health problems in Scotland and the asylum grew to accommodate all of those patients who had previously been housed in the City Bedlam.

From the beginning, the management of the asylum was based upon principles of kindness and non-restraint. Patients were provided with books and other reading material and encouraged to work to keep themselves busy.

In 1839, with the appointment of the first Resident Physician Superintendent Dr William McKinnon, the asylum more closely followed the principles of ‘moral therapy’ or ‘moral treatment’, whereby patients were encouraged to exercise their minds and bodies to keep occupied and entertained. In addition to setting up one of the first patient libraries in Scotland, various workshops were set up in the grounds of the hospital, including a blacksmith, carpenters, upholsterers, and printing office.

In 1845, patient magazine The Morningside Mirror was launched, written and edited entirely by the patients themselves and printed on the asylum’s own printing press. This magazine continued to be published and printed in-house until 1912, almost one hundred years after the admission of the first patient.

The Royal Edinburgh Hospital had come a long way from its slow beginnings, and treatment for people with mental illnesses in Edinburgh was a long way from the “deplorable conditions” that had been experienced by Fergusson.

Author: Isla Macfarlane

References

Checkland, Olive. Philanthropy in Victorian Scotland: Social Welfare and the Voluntary Principle. John Donald Publishers, Ltd, 1980.

Duncan, Andrew. A Letter to His Majesty’s Sheriffs-Depute in Scotland, Recommending the Establishment of Four National Asylums for the Reception of Criminal and Pauper Lunatics, by Dr. Andrew Duncan Sen. Edinburgh, 1818. Lothian Health Services Archive, LHB7/7/3.

Henderson, David Kennedy. The Evolution of Psychiatry in Scotland. E. & S. Livingstone Ltd, 1964.

Juvenal. The Satires. Translated by Niall Rudd, Oxford University Press, 1992.

Mitchell, Arthur. Memorandum on the Position of the Royal Edinburgh Asylum for the Insane. 28th December 1882. Morrison and Gibb, 1883.

Report by the Managers of the Royal Edinburgh Asylum for the Year 1841… Edinburgh, 1842.

Images from the Wellcome Collection.

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources