Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

Fear of false imprisonment was a growing concern in eighteenth century Britain. Private madhouses, where the inmates were paying customers, were particularly susceptible because there was little oversight of their practices. Although legislation to regulate asylums was introduced in 1774 its powers were limited and flagrant abuses of the system continued.

As the number of asylums increased dramatically over the course of the nineteenth century they were increasingly used to house individuals who were not necessarily a threat to themselves or others, but rather viewed as a social inconvenience. This was of particular concern to wealthy individuals, where any actions which didn’t comply with social norms could be seen as damaging to the reputation of entire families.

Public fear that incarceration could be used by families to obtain the patient’s estate or to free up a spouse to remarry was also widespread and was a subject depicted in popular culture, including in the work of Daniel Defoe.

Growing concerns about this misuse of asylums led to the establishment of a select committee to investigate the issue in 1815. While subsequent legislation expanded the responsibilities of magistrates, an effective nation-wide system of regulation was not introduced until 1845. In large part this new legislation was the result of extensive public campaigns. Particularly prominent in this was a group, which included ex-inmates, who had formed a body called the ‘Alledged Lunatics Society’ in the 1840s.

The author of this book, Reverend Henry Newcome, was on holiday in Scotland in 1859 when his wife and sister became concerned that he seemed unwell. Newcome decided to visit a doctor to relieve their doubts. He was then detained in a private asylum in Edinburgh for nine months. This detention cost Newcome approximately £500.

Written thirty years later, this text details his initial medical assessments and treatment.

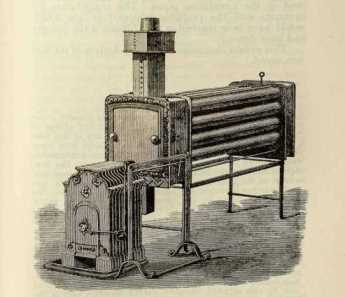

One physician believed Newcome’s invention of a ‘stove which will heat the room by the consumption of a newspaper in it’ was proof that he had ‘lapsed into an imbecile state’. This invention was no fantasy, however, and Newcome had already patented it six weeks before being detained. He also later received an Honourable Mention for his invention at the Smoke Exhibition in South Kensington in 1882.

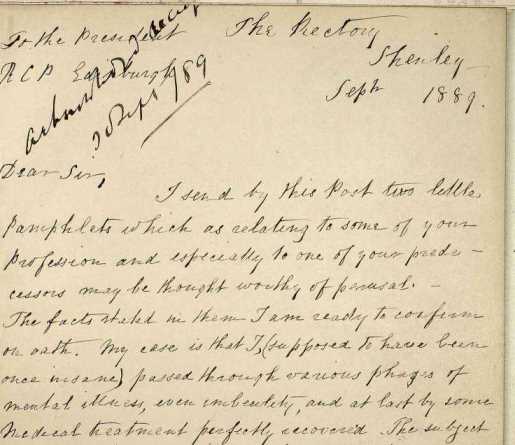

Our edition of Newcome's work includes a letter he wrote, which is addressed to the President of the Royal College of Physician of Edinburgh. In it Newcome states that 'with many of your profession, their hearts are better than their heads'. He asks for the President's assistance, hoping to get a formal review of his case and certification of his sanity to demonstrate to his family, friends and parishoners his fitness to remain outside the walls of the asylum and continue his work. There is no record of any reply to this letter.

Newcome notes he remains unsure as to why he was detained but hopes ‘if anyone should find himself, through the fears of an affectionate wife, inside a private asylum, he will at least learn from my experiences what not to do’.

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources