Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories

The early modern period, and in particular the 1700s, was a time of significant architectural accomplishment. The city of Edinburgh is an especially illustrative example of this with the building of New Town. Streets were becoming wider and more uniform, and buildings and interiors were becoming more refined for specific purposes. In this context, it is not surprising that hospitals and medical institutions were interested in developing new purpose-built structures.

This period also saw a move from medical practitioners wishing to represent themselves in relation to individual patrons toward a trend of publicising their links to particular hospitals and institutions. For this reason many of the prints in this collection incorporate images of buildings into the portraits in some way.

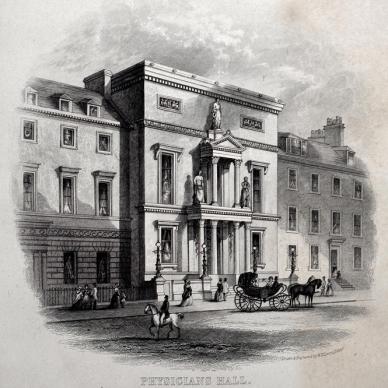

Physicians’ Hall, George Street, Edinburgh, premises of the Royal College of Physicians from 1781-1843. Originally, the Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh met in the private houses of the officials. By 1698 the College resolved to buy a building of its own and in 1704 it acquired a house and grounds in Fountain Close near the High Street, where they laid out a physic garden. In 1775, the new Grecian style Hall was built by James Craig in George Street. The foundation stone was laid by William Cullen. In 1781 the college moved to the new hall and sold the old premises. However, the stay on these premises was short lived. The building was sold in 1843 to the Commercial Bank and the College moved to its current premises in Queen Street.

Physician’s Hall, Queen Street, Edinburgh was the third hall inhabited by the Royal College of Physicians. The building was completed in 1845. It was designed by Thomas Hamilton in the Neoclassical style. The façade is highly decorative and specific to its purpose as a Physicians’ hall. Above the Corinthian-columned portico stand statues of Hippocrates, Asclepius, and Hygeia carved by A. Handyside Ritchie. The Royal College of Physicians is still based in these premises on Queen Street today.

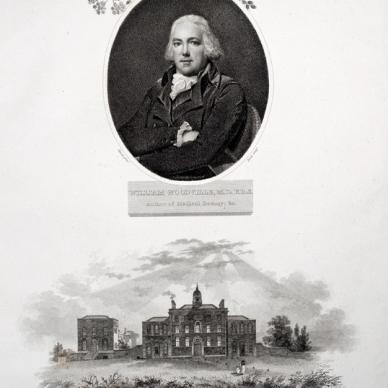

William Woodville (1752-1805) was a physician and botanist born in Cumberland. He studied at the University of Edinburgh, obtaining his MD in 1775. He later relocated to London where he worked as physician to the Middlesex Dispensary. In 1784 he joined the Royal College of Physicians and the Physical Society at Guy's Hospital. He was granted the position of physician to the London Smallpox and Inoculation Hospital at St Pancras in 1791, a charitable institution that provided smallpox inoculations and treated the disease. After Edward Jenner’s discovery of the vaccination Woodville quickly adopted the technique and became one of the procedures’ keenest advocates.

Below the portrait of Woodville is a picturesque image of the Inoculating Hospital at St. Pancras. The composition of the print is similar to a number of other images in the collection and demonstrates the importance of the link between medical practitioners and the institutions with which they were involved.

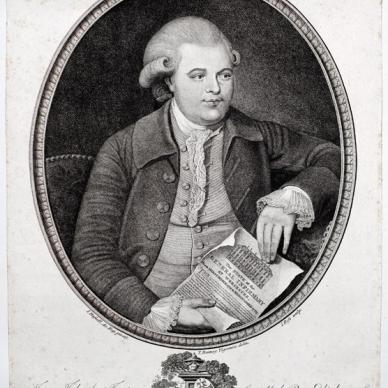

James Johnstone Junior (1753-1783) was a physician born in Worcestershire. He attended the University of Edinburgh in 1770 to study medicine where he was taught by two eminent medical professionals John Gregory and William Cullen. He also became a member of the Medical Society. In 1774 he moved back to Worchester and obtained the position of physician at the Worchester Infirmary. Johnstone began to tackle typhus treating the prisoners in Worchester Castle.

Stipple engraving is a method of rendering tones with dots and short flicks. It involved a mixture of etching and engraving. It was not used widely until the middle of the eighteenth century. In comparison to mezzotint it can produce a relatively high yield of prints with little deterioration in quality.

Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories