Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

Working-class skin was a source of fear and a source of knowledge. In the 1800s an increased understanding of contagionist theory lead to an increased fear of the proximity of poor bodies. The repulsion felt towards beggars and the destitute could now be justified not just on moral grounds, but on medical ones too. While middle-class bodies were increasingly viewed as controlled and sanitary, working-class bodies were the opposite – chaotic and unwashed.

But it was this same working-class skin which was central to the development of dermatology as a medical specialty. The establishment of charitable hospitals and dispensaries in the 1700s and 1800s allowed physicians and surgeons access to patients on a scale never before experienced. While well-off paying patients frequently objected to having their skin prodded, experimented on and displayed in printed texts, charitable patients had no option but to agree. Their skin, time and again, was used as the source of dermatological discoveries.

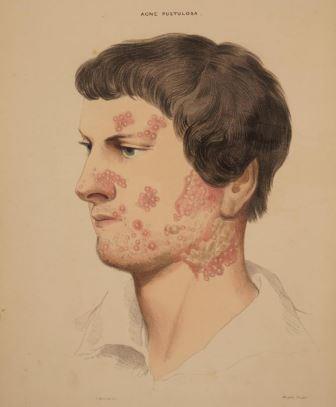

Whether acne was a sufficiently serious skin complaint to be addressed by medical practitioners was a subject of debate in the 1700s and 1800s. The surgeon Daniel Turner, writing in 1731, defended his own interest in the treatment of acne, ‘I shall make no Apology for spending Time, or taking the same Pains to remove the Blemishes incident to the Face by some. I cannot think the Talk below the Dignity of a Physician’.

The acne of the anonymous individual in this illustration, a patient at St Thomas’s Hospital in London, was treated with a poultice of bran and opium. Another common treatment for acne in the 1800s was mercury. Its skin lightening effect reduced the appearance of blemishes, although with the side effects of kidney problems, birth defects and chemical burns.

Scabies is a skin inflammation accompanied by severe itching caused by the itch mite Sarcoptes scabiei. The mite passes from person to person by close contact and is particularly common in areas which are affected by overcrowding and poverty.

It was only in the mid-1800s that it was proven that the itch mite was the cause of scabies. Before then many theories abounded, the most popular being that scabies was a sexually transmitted disease, similar to syphilis. Anti-Scottish sentiment in England in the 1700s led to scabies, or ‘the itch’, being particularly associated with the Scottish in medical publications and satirical prints. It was also euphemistically known as the ‘Scotch itch’ and the ‘Scotch fiddle’. The Scottish were, according to this theory, more uncivilised, more unclean and more immoral than their English counterparts. ‘Itch-land’ became a slang term for Scotland.

This illustration shows an unknown patient suffering from infected eczema. It remained common in the mid-1800s for physicians to intentionally avoid attempting to cure eczema. Earlier ideas about keeping the body in balance led to arguments that diseases which oozed, or expelled fluid, were health-giving. Doctors often argued that it was dangerous, even potentially fatal, to treat eczema because it would cause toxins to build up in the internal organs.

It was even recommended that patients be wrapped in rubber sheets to encourage the discharge. Other similar methods included the use of bloodletting, diuretics and laxatives. Ferdinand Hebra, author of the atlas this illustration was included in, disagreed with this approach. Hebra recommended a wide range of treatments, including tar and skin peels. Other common treatments included the ingestion of sulphur, arsenic and mercury.

Crocker, an English dermatologist, was a pioneering educator and researcher in the field of skin diseases. He worked as chair of dermatology at University College Hospital, London and was an avid painter – many of the illustrations in his books are his own composition or based on his sketches. Crocker’s reputation grew to such a height that he was able to run a successful private practice out of offices on London’s Harley Street.

Crocker's greatest claim to fame was to be the first physician to attempt a diagnosis of Joseph Merrick, whose life was dramatised in the 1979 film The Elephant Man.

Three different patients are illustrated here. Figure one shows the case of a 53-year-old ship’s steward who blamed his skin complaint on fragments of metal entering cuts on his skin when cleaning brass work aboard ship.

This blog was developed to accompany the exhibition Skin: A Layered History, which ran from 10 February 2023 to 13 October 2023.

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources