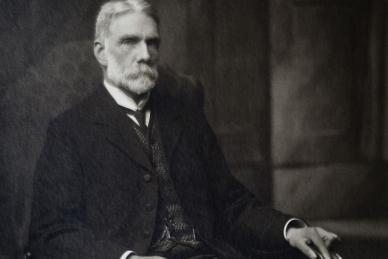

William Russell

(1852–1940)

College Role:

President

Notable Achievements

In 1880, Russell was appointed late house physician and pathologist, General Hospital, Wolverhampton.

In 1882, Russell was appointed honorary physician, Carlisle Dispensary.

In 1885, Russell was made lecturer on pathology, School of Medicine, Edinburgh.

In 1890, he was appointed pathologist, Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh.

Russell was made assistant physician at the Royal Infirmary in 1892.

In 1908, he was appointed physician and lecturer on clinical medicine at the Royal Infirmary.

In 1913, he was appointed Moncrieff Arnott professor of clinical medicine.

Russell was president of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh from 1916 to 1918.

Russell was made emeritus professor in 1919.

Key Publications

Russell wrote extensively on blood pressure, arterial constriction and peripheral resistance.

Biography

William Russell was born at Douglas, Isle of Man, where his father, a native of Wick, served as an officer controlling fisheries. His mother, née McPhail, also hailed from Caithness. He studied medicine at Edinburgh, qualifying MD, a gold medallist, in 1875, four years before the opening of the new (Victorian) Royal Infirmary buildings.

In 1894, at 42, he married Beatrice Ritchie, one of his pupils in the extramural school. They had six children, four of whom qualified in medicine. A son (Ivan) died in infancy of ‘surgical’ tuberculosis: the pandemic of tuberculous mastitis in its urban cows had made Edinburgh the world capital of surgical (bovine) tuberculosis before the 1914 war. Their third daughter, who went to Russia as a relief worker and married a White Russian, emigrated to Canada, where she died in the 1960s or 70s.

William Russell’s early publications dealt with interesting case histories, the nature of heart murmurs, successful treatment of empyema by aspirations. In his 1885 lecture on pathology he refers to his ‘great teacher, Lister’, and the importance of Koch’s new bacteriology; in 1892 he spent some time in Koch’s domain in Berlin to study a cholera epidemic.

In 1890 his experience of pathology, alongside clinical medicine, made him publish a paper on ‘a characteristic organism of cancer . . . Fuchsine bodies . . . a yeast-like fungus in 43 out of 45 cases . . .’, and reverted to this in The Lancet in 1899. Russell’s Fuchsine bodies were accepted into the literature of pathology, but were interpreted otherwise after his death, by PAS staining etc., as polysaccharide containing inclusion bodies in the round cell infiltrates at the periphery of malignant tumours, in plasmacytomas and chronic granulomas.

The early years of the century brought numerous papers by him on blood pressure, arterial constriction, on peripheral resistance, and on the relationship of arterial ‘hypermyotonia’ and spasm to the eventual emergence of arteriosclerosis. He would have approved of the later demonstration of spasm by angiography, and of modern investigations of the arterial wall, where he had groped blindly by traditional palpation of the pulse.

The stomach seems to have been his other main clinical interest, viz. papers on acid secretion, on pyloric stenosis and the use of X-rays in the diagnosis of stomach cancer. In retrospect, it is easy to belittle the limited therapeutics of the time, and the reliance placed on changes in diet, even in acute vascular events.

In academic politics he was an early protagonist of women in medicine; he taught at the women’s schools, and was the first ‘chief’ to open his wards to them at the Royal Infirmary before the First World War. In a 1901 paper he extolled the extramural school of the Royal Colleges as the best training ground for professors and lecturers in the Empire, no less than 50 at that time, despite all lack of endowments. It is perhaps surprising that Edinburgh University then made him the first Moncrieff Arnott professor of clinical medicine in 1913.

He was elected President of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh in 1916, but declined re-election in 1918 on account of ill health.

He was much concerned with the social dimensions of medicine, and opened a debate at the College on Lloyd George’s National Insurance Act of 1912. When he became President in 1916 the Great War dominated the scene, and during his presidency the College agitated for the proper care of disabled soldiers. It also supported plans for a Ministry of Health, but not until after the end of the war. He initiated constitutional changes to allow women to become members of the College.

Russell vacated his chair in 1919. In 1921, in his presidential address to the Caledonian Medical Society, he welcomed social progress seen during his own lifetime, referring back to 50 years before his birth when Scottish miners had still been serfs who were liable to be sold with their coal mine. Despite the disasters of 1914–18, he remained politically optimistic and put his faith in the League of Nations in his last book which he published, aged 80, in 1932. In this work, Old Beliefs and New Knowledge, he wrote of his religious difficulties, of the need to purge the Old Testament and accommodate modern archaeology and science in a non-fundamentalist way.

His daughter-in-law recalls him as a little remote, but as a very likeable man who was not an obsessive churchgoer, but who practised his Christianity by supporting ‘lame ducks’ and entertaining them with his wife at their house. His obituarist Edwin Bramwell, a close friend and his successor in the chair and the College presidency, described Russell as ‘somewhat egotistical at times . . . an attractive trait, for one never knew whether or not he was laughing at himself’.

He died in 1940 after two years of dementia. His daughter Helen wrote at the end of her life ‘. . . my father had a streak of that terrible thing, love which is not blind’.