Introduction

Stoke Mandeville Hospital (SMH) is one of the most recognisable hospitals in the UK because of its association with the renowned National Spinal Injuries Centre (NSIC). The NSIC, one of the largest specialist spinal injuries centres in the world, is where Sir Ludwig Guttmann pioneered the rehabilitation work that led to the Paralympic Games. Mandeville, one of the official mascots of the 2012 London Paralympic Games, was named in honour of the hospital’s contribution to Paralympic sport. Contrary to general belief, this establishment is not only a spinal injuries centre; it is a district general hospital with a large spinal injuries centre. Furthermore, despite its fame, the NSIC has only been in existence since 1944.

The hospital originates in the 1830s when a cholera epidemic swept the country and over 50 people died in Aylesbury. Funded jointly by Aylesbury and Stoke Mandeville this cholera hospital was established on the parish border between the two communities, as cholera was so contagious, and the risk of infecting the local population was too great.1 An isolation hospital was built in the 1890s and it features on the 1900 Ordnance Survey map. By the start of the twentieth century it had developed into a ‘fever’ hospital treating all forms of infectious diseases and a new ‘isolation’ hospital was added in 1933.2 In 1939, this 90-acre empty site with potential for additional building was acquired by the War Office as an Emergency Services Hospital.3

Today, it is a large National Health Service (NHS) hospital, part of the Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust. The purpose of this paper is to document the setting up of such an iconic hospital. The author worked there between 1956 and 1992 and kept abreast of developments.

Historical background on the treatment of spinal injuries

SMH is primarily known for its internationally renowned spinal injuries centre.

Injuries of the spinal cord were first described in the Edwin Smith surgical papyrus, a text originally written in Egypt about 3000 BC and subsequently by Hippocrates (circa 460–370 BC). There are references to spinal paralysis in both the Old and the New Testaments, and Paul of Aegina described reducing a fractured spine (AD 625–690). Although paralysis features in the literature during the Renaissance, few survived their injury and little progress was made until the twentieth century.4

The first successful account of the management of spinal injuries was by Wilhelm Wagner (1848–1900), a general surgeon working in the accident hospital for coal miners in Königshütte Hospital in Upper Silesia, Germany. He developed a practical method of treatment and demonstrated that patients could be kept alive and rehabilitated. In Switzerland, Theodor Kocher (1841–1917), professor of surgery at Bern, was also caring for patients with a spinal injury and carrying out anatomical and physiological research. Wagner and Kocher’s textbooks became standard works of reference for the treatment of spinal injuries.4

With the advent of the First World War, Otto Marburg (1874–1948), a professor of neurology from Vienna commissioned in the Army, set up a specialised unit to treat soldiers with spinal injuries, with physiotherapists, physical medicine doctors, urologists, neurologists and orthopaedic surgeons. A mark of their success is that they kept a French prisoner of war alive for 2 years free of pressure sores and within weeks of his repatriation to France, he was covered in them.4

The German neurologist Otfrid Foerster (1873–1941) is of particular relevance as he trained Ludwig Guttmann. Foerster, one of the distinguished neuroscientists of his time, was also a physiologist and a self-taught neurosurgeon with an obsession for rehabilitation, ‘making the lame walk and the blind see’.5 He learned the value of physiotherapy from the neurologist Heinrich Frenkel (1860–1931) and as a medical scientist, he correlated structure and function. Until 1914, neurosurgery was carried out by general surgeons but, when the war broke out, they were preoccupied with treating the wounded. Foerster, at 40 years of age, had to carry out the neurosurgery himself, taking the form of sutures of peripheral nerves and operations on the spinal cord.6 Whilst his field was peripheral nerve injuries, the rehabilitation principles he applied and subsequently imparted to Ludwig Guttmann became just as applicable to the treatment of spinal injuries.

The UK was unprepared for the First World War and the provision for the treatment of the 2 million wounded was woefully inadequate. The treatment of spinal injuries was dire and soldiers developed pressure sores and urinary sepsis leading to a high mortality. The majority died on the battlefield and the few who survived such a traumatic injury were transferred to the base hospital in Boulogne where they were treated by Gordon Holmes (1876–1965). Some officers were transferred to the UK, to the Empire Hospital in London where they were cared for by George Riddoch (1888–1947), the resident medical officer. The few long-term survivors were treated on a custodial basis at the Star and Garter Home where no urologist or any other consultant visited. The First World War, with an unprecedented number of casualties, had shown that the existing methods of treatment were unsatisfactory, there was no triage and wounded soldiers were admitted indiscriminately to general military hospitals where they died. The few survivors were ignored.

When the war ended, the units closed down in all countries and doctors returned to their pre-war appointments. Marburg continued as professor of neurology in Vienna, Holmes and Riddoch were appointed to the staff at the National Hospital for Nervous Diseases at Queen Square but they practised general neurology and were not treating patients with spinal injuries.

Medical provision in the UK during the Second World War

In contrast to the First World War which was unexpected, the rise of Hitler in Germany meant that another European war was inevitable and provision had to be made. Based on the experience of the Spanish Civil War, the Royal Air Force estimated that at the outbreak of the Second World War, a million beds would be required and half the contingent of doctors would be treating only civilians. Medical provision was fragmented and inadequate, there was a lack of central organisation and care was on an ad hoc basis relying on voluntary hospitals, infirmaries and general hospitals. There was a shortage of 353,000 beds and insufficient staffing.4 The problem was fivefold: beds would be lost in London because of the air raids, extra beds would be required because of the expected casualties, existing patients would need to be evacuated out of London to free beds, new hospitals would be required to accommodate those patients outside of the capital. Finally, specialist facilities would be needed to treat burns and locomotor injuries, head and peripheral nerve injuries and spinal injuries.

The Emergency Medical Services: 1939–45

The Emergency Medical Service (EMS) was set up as a temporary measure to reorganise the hospital services, especially in London, in order to meet the threat of bombing and prepare for air raid casualties. The authorities estimated that some 1,000 tons of bombs would be dropped on London on the first day of the war and 1 million beds would be required to treat the casualties. The surgeon Sir Claude Frankau (1883–1967) became director of the London and Home Counties section of the EMS.

London and its outer region were divided into 10 triangular ‘sectors’ that radiated from the centre of the Capital into the Home Counties (to include Essex, Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Surrey and Kent) based on the location of the major London teaching hospitals. Each sector was based on a large teaching hospital whose patients had to be evacuated so that expected casualties could receive treatment. Each sector would be run from a peripheral base hospital several miles out of London. The Middlesex Hospital was allocated Sector V, which extended to Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire. Outlying hospitals requisitioned as war hospitals to receive patients included voluntary hospitals, asylums, isolation hospitals, ex-workhouses, infirmaries and mental hospitals. In Buckinghamshire, Sector V included The Royal Buckinghamshire Hospital, The Tindal (mental) Hospital, a psychiatric hospital, Bierton Hill Aylesbury, an ex-workhouse and the fever hospital at Stoke Mandeville.

Under the aegis of the Ministry of Pensions, SMH and its large empty site was expanded under the EMS scheme. To address the shortage of beds,7 large hutted wards were built, out of wood because of a shortage of bricks, just north of the isolation hospital. Their life span was expected to be up to 21 years.

To free beds in the London hospitals in preparation for air raid casualties, patients were transferred from the Middlesex Hospital to the south wing of SMH. In addition the entire staff of the ‘massage’ department (this was the name of the physiotherapy department before it changed its name) were also relocated there together with doctors and students. The late Professor Denis Baron, the author’s cousin, remembered coming out as a student during the war to examine clinical cases.8 This association of SMH and the Royal Buckinghamshire Hospital with the Middlesex Hospital in London lasted until the middle of the twentieth century.

Much of the hutted hospital that had been built as a ‘reserve emergency hospital’ at the beginning of the Second World War did not receive a major influx of casualties so the hutted wards were taken over for other purposes and run by the Ministry of Pensions. At SMH, there were general medical facilities, a plastic surgery unit as part of the provision for specialised care, pathology, an X-ray department and operating theatres.9 Early emphasis was on burns and fractures, including spinal injuries in which it later came to specialise.

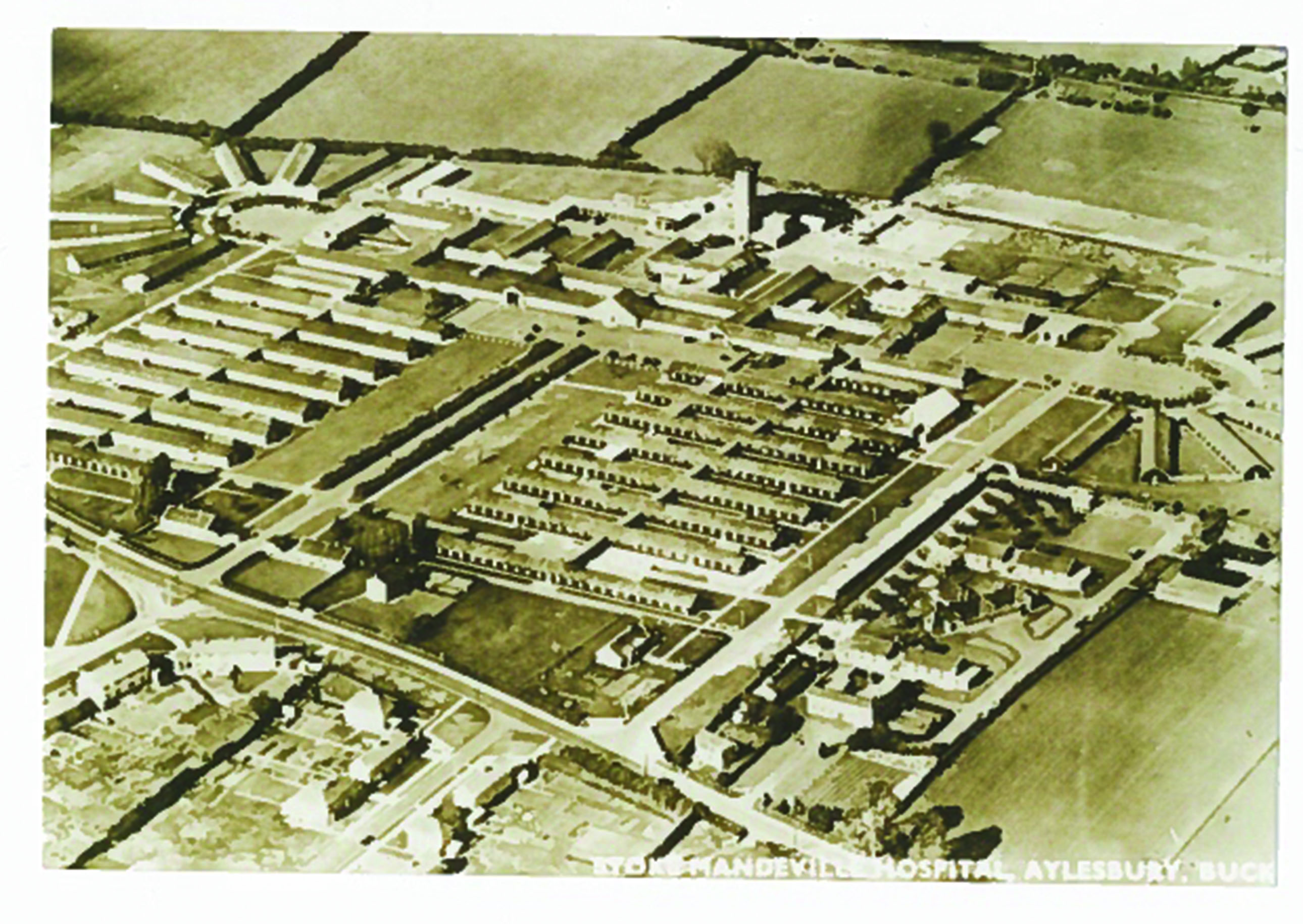

Initially the hospital was administered by the Ministry of Pensions on behalf of the Ministry of Health under the EMS. Later it became entirely a Ministry of Pensions Hospital for the treatment of war disabled. The main hospital continued under the aegis of the Ministry of Pensions until 1 September 1951, when control passed to the Ministry of Health, under the aegis of the local Hospital Management Committee, with the exception of the NSIC, which was still under the Ministry of Pensions until 1954 when it fell under the aegis of the Ministry of Health. The centre finally came under the control of the NHS in 1954 (Figure 1).2

Figure 1 Aerial view of Stoke Mandeville Hospital with the National Spinal Injuries Centre. This is a standard Emergency Medical Service hutted hospital (Stoke Mandeville Hospital postcard)

The history of the setting up of the NSIC at SMH

The need for specialist facilities emanated from the experience of treating casualties of the First World War when it became apparent that soldiers suffering from burns, peripheral nerve injuries, orthopaedic injuries and spinal injuries needed specialist care. Only two doctors had the knowledge and the experience to treat patients with spinal injuries, experience gained during the First World War. By 1939, however, Holmes was too old and George Riddoch, who was chairman of the Medical Research Council Committee on Peripheral Nerve Injury, was given the task of setting up spinal injury units across the UK. Four units were designated to receive acute spinal casualties: the Agnes Hunt and Robert Jones Hospital at Oswestry; the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital at Stanmore; the EMS hospital at Winwick, Warrington; and, Bangour in Scotland. These four units, set up in 1941, were attached to other units; neurological, neurosurgical or orthopaedic.10 The treatment was woefully inadequate. There were inadequate numbers of staff who were untrained, the doctors gave priority to their other responsibilities, they had no equipment and they had no knowledge of how to treat patients with spinal injuries.

Thomas S Dick, worked in one of those hospitals, Winwick, where he was attached to the neurology and peripheral nerve injury unit. In his spare time, he was expected to look after the patients with spinal injuries. He described how the patients all had pressure sores, were scattered around the hospital and after 3 years were no better than when they came in. It is not enough to give orders saying that a spinal unit should exist; it requires dedicated staff who understand the treatment. Just leaving the patients scattered round the country in different wards, being neglected, meant that their condition deteriorated, and the patients died because of urinary infections and pressure sores. They needed unremitting care by devoted specialists 24 hours a day.11 Riddoch, with his experience, visited the units, making suggestions, trying to organise research and even offering to do the neurological work. The units were pervaded with a sense of hopelessness and helplessness. This dire situation prevailed until 1944 when Ludwig Guttmann came to SMH.

The NSIC 1944–83 and Sir Ludwig Guttmann

The NSIC, a name coined by Guttmann (1899–1980), was founded in 1944 to treat servicemen who had sustained spinal cord injuries in the Second World War.9 It is one of the largest spinal injury centres in the world and it has contributed to the reputation of SMH.

Born in Upper Silesia, Ludwig Guttmann studied medicine at the Universities of Breslau and Freiburg. He was an orderly in Königshütte and then, in 1929, he became first assistant to Foerster at the hospital in Breslau where Foerster was physician in charge of the neurological department. There he trained in the rehabilitation of patients with peripheral nerve injuries but he lacked practical experience in treating spinal injuries. In 1933, he was expelled from his post under the Nazi Enabling Laws and worked at the Jewish Hospital in Breslau. He fled Germany in 1939 just before the outbreak of war and came to the UK as a Jewish refugee. He spent 5 years in Oxford carrying out research at St Hughes and at the Radcliffe Infirmary under the neurosurgeon Hugh Cairns. He bitterly resented not being allowed to use his neurosurgical skills to operate on patients. When war broke out, he asked Cairns if he could treat patients but this was refused and he wanted to give up his research work and become a general practitioner. Eventually, in 1944, Riddoch asked him to lecture at the Royal Society of Medicine on the treatment of peripheral nerve injuries. When the second front opened, a spinal unit was supposed to be set up at the Nuffield Orthopaedic Hospital to serve the South of England but Professor Herbert Seddon (1903–77), the director in charge, refused to release beds.12 The unit was established at Stoke Mandeville instead in March 1944 and Ludwig Guttmann was appointed as resident medical officer in charge. Upon arrival he found no equipment, no staff, no bedpans, no physiotherapists and patients scattered throughout the hospital on different wards. He set to work and the principles imparted to him by Foerster became the bedrock of the treatment of spinal injuries. The centre started with 24 beds and one patient; within 6 months 50 patients had been admitted. By 1960 there were 190 beds and 50% of patients were admitted within 2 days of injury.13

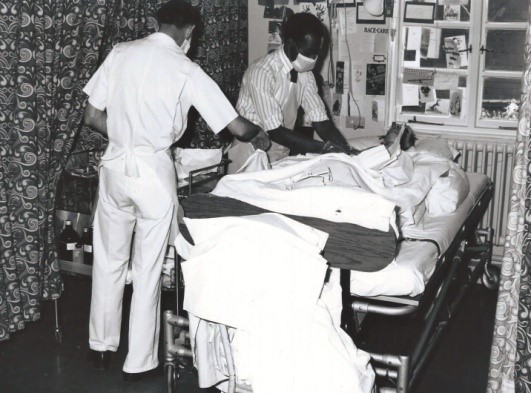

Guttmann was an energetic man, who tolerated no opposition from politicians, administrators, doctors or members of staff. He insisted that every aspect of the patients’ care was his responsibility (he never took a holiday). He saw patients on admission, sometimes in the ambulance or on a stretcher, weekly on the ward rounds and later in the physiotherapy and occupational therapy departments. This was in contrast to the organisation in the teaching hospitals in the UK where the consultant visited once or twice a week.14 Initially, he visited the patients at night to check that they were being turned regularly and he carried out the catheterisations himself. He imbued patients and staff with his will and dynamism. After initial resistance, the physiotherapists became enthused with his new methods of treatment incorporating exercise and making the patients independent (Figure 2). Later on, his mark was felt in other spinal centres and Stoke Mandeville served as a benchmark; it was no longer acceptable for the patients in other spinal injuries centres to have pressure sores. Staff were seconded to SMH to learn Guttmann’s methods.

Figure 2 Guttmann teaching the physiotherapists in the ward. Personal photograph

He instituted a Prussian regime in the Foerster tradition of medicine and ran the centre as a German academic department. He designated himself director (dictator), the sole consultant with responsibility for all the patients needing care. There were no other consultants. The visiting consultants, neurosurgeons, orthopaedic surgeons, plastic surgeons, urologists were expelled. He had three assistants, senior hospital medical officers, without a higher qualification between them who had no independent responsibilities and merely carried out his orders. Guttmann, who trained in Germany in psychiatry and neurology, where these are one and the same discipline, was influenced by the Germanic approach to medical practice as described by Lifton:

Individual German psychiatrists had always identified themselves as servants of the state, rather than as independent practitioners. Mental institutions especially were part of the administrative structure of the state, and the same could even be said of university medical departments. The long standing arrangement when internalized and buttressed by German cultural stress on authority and obedience, made it difficult for individual psychiatrists to consider or even imagine defying the state when summoned to participate in virtually any kind of project.7

Whilst this could be effective, it stifled independent thought and the only criterion for treatment was not what the truth was or what was best for the individual patient but in the German tradition, that it should please Ludwig Guttmann. Any contrary views or views that came from outside would be greeted with the statement ‘we taught the world how to treat spinal injuries’.15 Guttmann trained and supervised all auxiliary and nursing staff. He rejected the English hierarchical system of visiting consultants giving orders and departing or not attending at all. He gathered the patients together on one ward and he trained the staff when first appointed. He held the whole system together with rigid rules. He was ever present and took overall responsibility for all aspects of the patient’s care. He showed by example that these patients could be successfully treated and his methods and ideas received acknowledgement and were adopted throughout Europe and the former British Empire.

In his Guttmann lecture, Frankel said that Guttmann was feared. He described a hierarchical structure that was later abolished. Guttmann adopted a dictatorial style with the physiotherapists. His doctrine of making everyone walk with callipers, including patients with high lesions, resulted in a complaint by Finkelstein, one of the patients. This practice was eventually abandoned but not before Guttmann had retired.9 Guttmann did not see the need for clinical psychology but after his departure a clinical psychology department was established.

The facilities

When the author worked there in the 1960s, the wards functioned well and doctors were pleased with them. They were single storey with no need for lifts and as there were no cubicles, the patients could learn from each other.

As facilities were required, they built conventional bricked accommodation. In 1954, when SMH transferred from the Ministry of Pensions to the NHS, a hydrotherapy pool was gifted to the hospital and it remains in use today. The occupational therapy department and the physiotherapy department were added together with a demonstration area. Sports facilities were built in huts but subsequently Guttmann took over the sports fields at the back of the hospital and raised funds to build the sports centre, all of which are still being used today with much benefit. After Guttmann departed, the hierarchical system after some vicissitude was abolished. While it had worked because of Guttmann’s knowledge and drive, he was an exceptional man and his methods founded on profound neurological and rehabilitation knowledge could not be replicated. Consultants in spinal injuries were appointed with full responsibility for their patients and visiting consultants were welcomed.

Twenty years later, however, the facilities were inadequate (Figures 3 and 4). All the treatment was carried out in the ward, the bowel evacuations, the catheterisations and the treatment of the pressure sores. Patients ate in the middle of the ward and initially physiotherapy took place there also. This situation prevailed for many years and when an American doctor who was visiting a private patient under the author’s care saw the pressure sores being dressed in an open ward, he told the author rightly (but to his surprise) that in the USA this would not be allowed because of the risk of infection. The unfortunate attitude at Stoke Mandeville was that nothing could be learned from others.

Figure 3 Crowded wards in the National Spinal Injuries Centre where patients were undergoing treatment in the wards. Personal photograph

Figure 4 The patients took their meals in the middle of the ward in the National Spinal Injuries Centre. Personal photograph

No new hospitals were built in the UK during the war and the hutted hospitals were in use for many years after the war. The huts were used as tuberculosis isolation hospitals until the decline of tuberculosis. In 1979, severe weather conditions caused structural damage to some of the wards at Stoke Mandeville that housed the centre. Water came through the ceilings that collapsed and three wards were rendered useless (Figures 5 and 6). As they were unable to meet the £2 million estimated repair and maintenance bill, the regional board decided they should close two wards. The centre’s future looked in doubt and patients faced the prospect of receiving care in nonspecialist hospitals without the wealth of expertise and knowledge built up at the NSIC over the years.16 In protest the patients chained themselves to the radiators with the aid of the senior nursing staff to exact maximum publicity on the morning of the opening of the Conservative Party’s conference. The minister of Health, Gerald Vaughan, was despatched to the spinal centre. Faced with maximum television coverage, and to gain credibility, he announced to the world that he was not just an administrator but he was a practising doctor. In the following question and answer session, the reporter put a figure to the Minister, which had been worked out jointly by him and the author on the back of a cigarette packet, and which Vaughan thought was the right amount. For the next 10 months politicians and NHS officials discussed the future of Stoke Mandeville and the NSIC and the subject was raised in the House of Commons. In the autumn of 1979, the focus was on raising £10 million to rebuild a new centre and on 23 January 1980 an ambitious fundraising campaign was launched at Church House Westminster. A collaborative team of consultants, doctors, nurses, physiotherapists and occupational therapists met with the architects to participate in the design of the centre at all stages. The NSIC was duly rebuilt and opened by HRH the Prince of Wales on 23 April 1983 following a successful and well-publicised fundraising campaign.

Figure 5 Damage to the wards after a flood and because of ageing facilities. Personal photograph

Figure 6 Damage to the wards after a flood and because of ageing facilities. Personal photograph

Fundraising

The rebuilding of the centre was the result of magnificent public support. The funding was multifaceted. Mrs Thatcher, the prime minister, was involved from the outset and she appreciated that whilst money could be raised from the public for wards and beds for the patients, it would be difficult to appeal for money for the enabling works such as the sewers and the building of roads. She had several million pounds left over from the Falklands War that she contributed. The Oxford Regional Board also agreed to fund the X-ray department and its equipment. Various celebrities gave large sums of money. Architects and captains of industry were approached and many undertook to do the work at cost or for nothing. There was a wide public relations scheme to welcome those who donated to the cause such as boy scouts, The Army, The Air Force and The Navy to come to SMH, and be taken round the hospital by one of the consultants to see the progress of the building work. Within 3 years, with the generosity of the public, £10 million was raised and the new facilities opened in 1983 (Figure 7).17 There were four wards with small four-bed bays, isolation rooms allowing privacy, conference rooms, a pre-discharge flat, a department of psychology and a dining room for the patients. It is deplorable that despite the superb support resulting in the building of a new spinal unit, a national scandal was subsequently unearthed that revealed that abuse of patients and their relatives had taken place at Stoke Mandeville Hospital and other hospital premises across the country.

Figure 7 The new National Spinal Injuries Centre. Picture courtesy of The Bucks Herald

Stoke Mandeville General Hospital

Up to this point, this paper has devoted itself to the history and the development of the NSIC but as has been pointed out in the introduction, it was part of a district general hospital. What was the effect of having such a large and famous centre on the same site? From the outset it must be acknowledged that SMH was an outstanding district general hospital with high standards. What was the role of the NSIC and its influence on the rest of the hospital and what was the influence of the hospital upon the NSIC? Initially under Ludwig Guttmann who concentrated all aspects of treatment, medical and surgical, into his own hands, virtually nil. He expelled and tended not to use visiting consultants or consultants from the hospital unless there was some dire emergency. After his retirement and the appointment of consultants in place of the senior hospital medical officers, a different approach was gradually adopted. The neurosurgeons, orthopaedic and urological surgeons, and chest physicians were welcomed to the centre from the outset so they could advise on treatment on all the patients and also learn from this exceptional group of patients. The patients were seen not just when complications or disasters had occurred. Different forms of treatment were attempted and research carried out to assess the best method. Consequently, whilst fixation of the spine had been condemned under the old regime, it was now practised as a routine as was a neurosurgical approach to syringomyelia. A dermatologist was welcomed to carry out collaborative research on the skin conditions affecting patients with a spinal injury. A chest physician carried out extensive research on the patients in collaboration with the Royal Brompton Hospital. SMH did not have an intensive treatment unit (ITU), a grave deficiency as many of the patients with a high-level spinal injury were on ventilators. They were treated in the NSIC scattered about the wards. Because it was essential to closely monitor those patients, an ITU for the whole hospital was established under the direction of the anaesthetists and the patients with high lesions and needing ventilation were transferred there. This functioning ITU was to the benefit of the hospital as a whole. Similarly, the need for a CT and an MRI scanner to treat patients with spinal injuries brought this innovative equipment to the hospital. The department of psychological medicine was set up to address the mental health of the patients and the superb physiotherapy department was developed, including a hydrotherapy pool. The development of the NSIC proved of benefit to the hospital as a whole, serving as a stimulus and a source of pride.

High Wycombe, now a large hospital, was a small memorial hospital. Milton Keynes, now a large general hospital, did not exist and the Radcliffe Infirmary only had a few beds with limited facilities. In the early 1970s, SMH was a complex of some 600–700 inpatient beds. Predominantly at ground level, the wards were of Nightingale design, which whilst restricting patient privacy, enabled the staff to see and to be seen down their length. In addition to medical facilities, it had superb specialised units, which was unusual at the time for a district general hospital. The plastic and burns unit, founded ahead of the spinal injuries centre, was one of only four such units in the country doing innovative pioneering work. There was a Medical Research Council rheumatology unit that attracted international students from all over the world. The paediatric unit under McCarthy pioneered allowing parents to stay overnight in the hospital to be near their children. The dermatology unit under Wilkinson also attracted international students. In 1974, the Buckinghamshire Area Health Authority was set up with clinical and operational responsibilities. However, strategic decisions were still taken externally. The facilities developed and SMH provided superb service that subsequently proved an embarrassment to the regional board that had planned that there should be one large district general hospital in the North, Milton Keynes, another large hospital in the South, High Wycombe, and that SMH should be shrunk considerably in size to be a nuclear hospital. The fact that there was a large spinal injuries centre funded by subscriptions amidst considerable publicity increased this embarrassment and made this strategy unpopular. Subsequent plans suggested that High Wycombe and SMH should be incorporated as one functioning whole. In April 1994 SMH became the SMH NHS trust with a statutory mandate to manage the hospital. In 2006, a large modern hospital was built on the site with Public Finance Initiative funding.

Stoke Mandeville has been synonymous with the NSIC but it is apparent that the activities of the spinal injuries centre were of benefit to the district general hospital and not only has it gained publicity for the hospital but unique skills and facilities developed in the NSIC have permeated the hospital to the benefit of all the patients.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to Allison Graham and Marie-France Weiner for their constructive criticism.

References

1 The Vale of Aylesbury Plan Stoke Mandeville Fact pack August 201. Aylesbury Vale District Council. https://www.aylesburyvaledc.gov.uk/sites/default/files/page_downloads/ST... (accessed 01/03/19).

2 Clarke KW. Royal Buckinghamshire and associated hospitals: a review of the first ten years in the National Health Service. pp. 23–8.

3 Hospital Records Database: A joint project of the Wellcome Library and the National Archives. Stoke Mandeville Hospital Aylesbury. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/hospitalrecords/details.asp?id=218&pa... (accessed 01/03/19).

4 Silver JR. History of the Treatment of Spinal Injuries. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. p.73.

5 Haymaker W, Schiller F. The Founders of Neurology (2nd Ed). Illinois: Charles C Thomas; 1970. p.555.

6 Kennard MA, Fulton JF. Otfrid Foerster 1873-1941. An appreciation. J Neurophysiol 1942; 5: 1–17.

7 Lifton RJ. The Nazi Doctors – Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide. New York: Basic Books Inc; 1986. p. 113.

8 Personal communication Denis Baron.

9 Frankel HL. The Sir Ludwig Guttmann Lecture 2012: the contribution of Stoke Mandeville Hospital to spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 790–6.

10 Silver JR. History of the treatment of spinal injuries. Postgrad Med J 2005; 81:108–14.

11 Dick TBS. Rehabilitation in chronic paraplegia. A clinical study (MD thesis). Victoria University of Manchester; 1949.

12 Silver JR, Weiner M-F. Sir Ludwig Guttmann: his neurology research and his role in the treatment of peripheral nerve injuries, 1939-1944. J R Coll Phys Edinb 2013; 43: 270–7.

13 Guttmann L. Spinal Cord Injuries – Comprehensive Management and Research. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1973.

14 Silver JR. Ludwig Guttmann (1899-1980), Stoke Mandeville Hospital and the Paralympic Games. J Med Biogr 2012; 20: 101–5.

15 Personal communication Ludwig Guttmann.

16 Private correspondence on the National Spinal Injuries Centre Buckinghamshire healthcare NHS Trust.

17 National Spinal Injuries Centre Our History. https://www.buckshealthcare.nhs.uk/NSIC%20Home/About%20us/nsic-history.htm (accessed 01/03/19).